“Suzy,” he croaked. Then he heard voices in the hall.

Probably Malise, wondering where the hell he was.

“He’s not in his room, so he must be in the bath,” Suzy was saying sleepily.

Thank God he hadn’t locked the door. Suzy banged on it.

“Someone to see you, Rupe.”

“Who the hell is it?” he said.

“It’s me,” said a blissfully familiar voice, and there in the doorway stood Billy.

For a second Rupert gazed at him, dumbfounded.

“Christ, do I ever need you!” he said in an unsteady voice.

“I know. I’m terribly sorry about Helen.”

“No, to get me out of this bloody bath,” said Rupert. “But give me a shot of morphine first. It’s on the chest of drawers in my bedroom.”

The sting of the needle entering his shoulder was the most wonderful sensation he could imagine.

“How the hell did you manage to get out of Janey’s clutches?” he asked.

Billy grinned. “I told her that sometimes water was thicker than blood.”

“Draw’s good,” said Malise. “We’re fourteenth out of sixteen.”

All the other riders were tremendously sympathetic and friendly.

“They can afford to be,” said Rupert. “They think we’ve had it.”

“Who are the favorites?” asked Fen.

“Americans, Germans, Swiss,” said Rupert. “We’re about a million to one. I’ve put a monkey on.”

“Don’t let Fen see any of the papers,” hissed Malise. “They’ve all crucified Jake.”

“Good,” said Rupert. Then, shooting a sidelong glance at Malise, he said, “It’s not the winning that matters, it’s the being taken apart.”

It was a tremendous boost to the British team to see Billy.

“Can’t you jump?” said Ivor.

“I’m going to sit in the commentary box with Dudley,” said Billy, “and be wildly partisan.”

“At least you’ll get the names right,” said Fen.

“I’m glad you think so, Fiona,” said Billy. “How’s Rupe bearing up?” he added in an undertone.

“He won’t talk about either Helen or Jake except to make the odd flip crack. He probably will with you. I think he’s going through hell, but I can’t quite work out if it’s violent possessiveness or murdered pride, or whether he’s suddenly realized he loves her.”

At seven-thirty they walked the course. Everyone agreed it was the biggest ever built in show jumping. Fen could walk straight underneath the parallel without bumping her head. Close up, for the first time she realized how huge the fences were.

“Can’t think why they don’t stage the Olympic swimming contest in the water jump,” she said.

Ivor’s mouth was open wider than ever. “It’s even worse than the individual.”

In front sauntered the American team. In their white short-sleeved shirts and breeches, showing off their mahogany suntans, long bodies, and thoroughbred legs, laughing and exuding quiet confidence, they looked as though they’d been fed on peaches and T-bones all their life. The crowd gave them a colossal cheer of encouragement as they passed. The German team looked equally together as they goose-stepped out the distances. But for the first time Fen felt there was real solidarity among the British team.

The arena was like an oven already. By the time I go in, thought Fen, it’ll be turned up to Regulo 10.

“That’s going to cause the most trouble,” said Malise, looking at the fence constructed in the shape of a huge brown derby hat. “It’s so unfamiliar, you’ll have to ride them really hard at it; then there’s that big gate immediately after.”

“At least they’ve scrapped the hot dog,” said Ivor, in relief. “All these flowers are giving me hayfever.”

Rupert broke off a frangipani and gave it to Fen.

“You’ll be had up for demolishing the course even before you start,” she said.

* * *

Malise was right. The derby fence upset everyone. Ludwig, the German pathfinder, expected to go clear, was nearly brought down by it, and knocked up sixteen faults.

“Roll on ze next Olympics,” he said ruefully, as he came out of the ring. “I am very bored of being ze good loser.”

Canadian, Australian, Italian, and French riders all came to grief. Jesus the Mexican had a punishing fall. The first American rider, Lizzie Dean, came in and cleared the derby, but ran slap into the gate and had eight faults at the combination.

“I can’t watch anymore. My self-confidence is in tatters,” said Fen. “The only good thing about this competition is Billy doing the commentary. He keeps saying “Hooray” every time a foreign rider kicks out a fence.”

“You’ll be jumping in three-quarters of an hour,” said Malise. “Better go and warm Hardy up. By the way, some flowers arrived for you. They’re in the tackroom.”

He allowed himself a small smile as Fen bolted the 400 yards to the stables. The flowers were two dozen pale pink roses and the card inside said, “To darling Fen, Good Luck, I love you, Dino.”

“How the hell did they get them delivered here?” she said.

“Carol Kennedy bought them,” said Sarah. “He promised Dino he’d make sure you got them. Stop grinning like a Cheshire cat. This is no time to be worrying about the opposite sex.”

“Having got these,” said Fen, putting them in a bucket of water, “I can now stop worrying about it.”

Because they were fielding only three riders, the British team started jumping with the second riders of the other teams. Among these, Hans Schmidt only had a couple of poles down for eight faults and Mary Jo came in and showed everyone how to do it, with a glorious clear.

“That should encourage Ivor,” said Fen, who had jumped off Hardy for a second to watch him.

Ivor rode in blinking. Not a seat was empty. After Mary Jo’s gold earlier in the week, and her clear now, the huge crowd was at fever pitch.

“I always enjoy Ivor’s intellectual approach to the sport,” said Rupert, from the shade of the riders’ stand. “Now Ivor has removed his hat, will he ever find his head again?”

After Tuesday’s fiasco, Ivor started well and rode with colossal determination. The sailboat, the derby, the high gate, the huge wall, the massive blue water jump caused him no trouble at all. Then he unaccountably stopped twice at the parallels.

“That’s that then,” said Rupert. “Let’s go and have a screw, Dizz.”

“For God’s sake get your bat out, Ivor,” Billy was yelling in the commentary box, to the startled delight of the viewers. “One more stop and the whole team’s eliminated.”

Scarlet in the face, as if by telepathy, Ivor pulled his whip out of his boot, in which it was tucked, and gave John half a dozen hefty whacks.

“Good God,” said Malise.

The picture of injured pride, John heaved himself over the parallel, and, swishing his tail in rage, proceeded to go clear, except for bringing down the middle element of the combination.

“Absolutely marvelous. Well done, Ivor,” said Billy, excitedly from the commentary box. “Do you know, he only paid £1,000 for that horse?”

“Ten faults, plus one time fault. That’s not at all bad,” said Malise.

Fen knew she should have some inner tap which could turn off all outside excitement and leave her icily calm. On Desdemona she’d always jumped best when she was angry. But Hardy needed to be kept serene. He seemed a little tired after his medal-winning adventures on Monday, which would at least make him jump more carefully and not start ducking out of his bridle. Following Jake’s lead, she had removed the cotton wool from his ears and let him go to the entrance of the arena, so he could watch the preceding round. It was both inspiring and daunting. Carol Kennedy went clear, to colossal applause, which meant the Americans were on twelve faults at the end of the third round, and could probably scrap Lizzie Dean’s round. The Tarzan howls and the waving American flags had Hardy hopping all over the place.

“The time is incredibly tight,” said Malise. “Don’t waste any of it in the corners. But remember, the important thing is to get round at all costs. If you’re disqualified we’re out.”

“You do say the cheeriest things,” said Fen.

“Good luck,” said Rupert.

Fen felt the butterflies going berserk in her stomach, as the terror finally got to her.

“I can’t face it,” she said in panic. “I simply can’t jump in front of all those people.”

“Yes, you can,” said Rupert, putting his good left hand up to squeeze her thigh. “Come on, darling, you’ll float over them. Hardy’s done it all before. Leave it to him.”

“Are you sure?” Suddenly she looked terribly young.

Rupert smiled. “Quite sure.”

Out in the arena there was nothing like it. Nothing like the fear and the exposure in that blazing white hot heat, watched by 200,000 eyes and millions and millions of television viewers.

Billy, who by now was well stuck into the whisky, admired the slender figure in the black coat, her blond hair just curling under her hat, one of Dino’s pink roses in her buttonhole.

“This is certainly the most beautiful girl rider in the world,” he said. “Riding Hardy, with whom her brother-in-law, Jake Lovell, did so brilliantly on Monday to get the silver medal. Now come on, darling.”

“I told you not to mention Jake,” hissed Dudley, putting his hand over the microphone, “and don’t call Fiona ‘darling.’ ”

The relief of the bell stopped all thought process. Suddenly Fen’s nerves vanished.

“It’s you and me, babe,” she whispered to Hardy as he cleared the first four fences without any trouble, kicking up the tan, following the hoofprints of earlier riders. She steadied him for the derby. He didn’t like it, then decided he did and took a mighty leap, clearing it by a foot. The yell of the crowd distracted him, the heat haze above the gate made judging the distance difficult. Fen asked him to take off too early, he kicked out the fence, and then toppled the wall after that, hurting himself, eyes flashing, ears flattened, tail whisking like an angry cat.

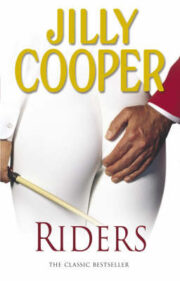

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.