“Don’t smother me, child, and there’s no need to cry. And as you don’t appear to have any transport, I’ll buy you a decent horse box for a wedding present.”

Jake shook his head. “I can’t believe it,” he said.

“There’s one condition,” Granny Maxwell went on with a cackle of laughter. “That the first time you appear at Wembley, you buy me a seat in the front row. I’m a bored old woman. In time, if you do well, I might buy a couple of horses and let you ride them for me.”

“If you really are going to buy us a horse box,” said Jake, “I’d better learn to drive properly and take a test.”

6

Six long months after she arrived in London in 1972, Helen Macaulay met Rupert Campbell-Black. Born in Florida, the eldest daughter of a successful dentist, Helen was considered the brilliant child of the family. Her mother, a passionate Anglophile and the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, was constantly reminding people of her English ancestry. In fact, a distant connection had come over, if not on the Mayflower, perhaps by the next boat. Mrs. Macaulay glossed over this fact and from an early age encouraged the young Helen to read English novels and poetry and admire all things English. Later, Helen majored in English Literature at the University of Tampa, where she was confidently expected to get a brilliant degree.

Deeply romantic on the one hand, Helen was also repressed by the rigid respectability of her family. The only proof that her parents had ever copulated at all were the four Macaulay daughters. Helen had never heard her mother and father row, or seen either of them naked. Her mother, who always insisted on women doctors, never mentioned sex, except to imply that it was degrading and wicked. Neither of her parents ever told her she was beautiful. Work to keep sin at bay, feel guilty if you slack, was the Macaulay motto.

Until she was nineteen, Helen never gave her parents a moment’s trouble. She worked at school, helped her mother in the house, never had acne or gained weight, and never answered back. At Tampa, at the beginning of the seventies, however, she came under the influence of the women’s movement — anathema to her mother, who believed a woman’s place was in the home. Her mother did, however, support the feminists’ view that a woman should never allow herself to be treated as a sex object, nor be admired for her body rather than her mind.

To her parents’ horror, Helen started getting caught up in student protest movements, demonstrating against the Vietnam war and joining civil rights marches. Even worse, she came home on vacation and said disparaging things about Richard Nixon. But far worse was to come. During her third year, Helen flunked out with a nervous breakdown, pregnant by her English professor, Harold Mountjoy.

Heavily married, but accustomed to the easy conquest of female students, Harold Mountjoy was quite unprepared for the torrent of emotion he unleashed in Helen Macaulay. It was Jane Eyre and Mr. Rochester, Charlotte Brontë and her professor all over again. Except that Helen was a beauty. Only a tremendous earnestness and dedication to study had kept her on the straight and narrow so long at Tampa. On campus she was known as the fair Miss Frigidaire. Harold Mountjoy set about defrosting her. Seeing her huge hazel eyes fixed on him, like amber traffic lights, during lectures he should have read caution. Instead, one day after class, he kept her back to answer a complicated question on Browning’s “Paracelsus.”

Discussing ambition in life, Harold had lightly quoted: “ ‘I am he that aspired to know, and thou?’ ” To which Helen had instantly, almost despairingly, quoted back: “ ‘I would love infinitely, and be loved!’ ”

Harold Mountjoy realized he was on to a good thing and asked her for a drink. Secret meetings followed; self-conscious letters weighed down by literary allusions were exchanged, and finally Helen’s virginity was lost in a motel twenty-five miles from the campus, followed by fearful guilt, followed by more motels and more guilt. Under Harold’s radical guidance, Helen embraced radical causes and on vacation shocked her parents even more.

Finally, towards the end of the summer term, Helen fainted in class. Her roommate, who, despite Helen’s attempts at secrecy, had regularly been reading her diary, went to the head of the faculty. He, in turn, was highly delighted, because for years he had been looking for an excuse to dump Harold Mountjoy, whom he regarded as not only immoral but, far worse, intellectually suspect. Helen’s parents were summoned. Appalled, they removed her from college. Her father, being a dentist, had the medical contacts to organize a discreet abortion. Helen and Harold were forbidden to see one another again. Harold, clinging to his job, terrified his wife would find out, complied with the request. This was the last straw for Helen. Losing her virginity had meant total commitment. She had expected Harold to tell her to keep the baby and to divorce his wife.

Desperately worried about her, her parents, who were kindly if rigid people, packed her off to England in the hope that this other great imagined love of her life would distract her. She was to stay for at least a year. Helen rang Harold Mountjoy in despair. He urged her to go. They would both write. In time they would meet again. There was a possibility he’d get over to England in August. At last Helen agreed.

The head of the faculty wrote to his London publishers, giving Helen an excellent reference and praising her diligence, and they agreed to give her a job, reading manuscripts, writing blurbs, and copyediting. He also fixed her up with digs with a female author in Hampstead.

So Helen pieced her broken heart together and came to England in October, unable to suppress a feeling of excitement that she would soon be able to visit St. Paul’s, where John Donne had preached, and Wimpole Street, where Robert Browning had courted Elizabeth Barrett. She might even get up to the Lakes to see Wordsworth’s cottage, or Haworth, home of the Brontës.

Sadly, England proved a disappointment. Accustomed to year-round Florida sunshine, Helen arrived at the beginning of the worst winter for years. She couldn’t believe how cold it was.

By day she froze in her publishing house, by night she froze at her digs, which were awful. The female author was an ancient lesbian who watched her every move. Upstairs was a lecherous lodger who made eyes at her at mealtimes and kept coming into her room on trumped-up excuses. The place was filthy and reeked of a tomcat, which her landlady refused to castrate. The landlady also used the same dishcloth to wash up the cat’s plates and the humans’ plates. The food was awful; they seemed to eat carbohydrates with carbohydrates in England. She found herself eating cookies and candy to keep out the cold, put on ten pounds, and panicked.

At the weekends she froze on sightseeing tours, shivering at Stratford, at the Tower, and on the train down to Hampton Court, and in numerous art galleries.

The English men were a bitter disappointment, too. None of them looked like Darcy, or Rochester, or Heathcliff, or Burgo Fitzgerald, or Sebastian Flyte. None of them washed their hair often enough; she never dared look in their ears in the subway. They also seemed de-sexed by the cold weather. They never gazed or whistled at her in the street. Anyway, Helen was not the sort of girl who would have picked up men. As the days passed, she grew more and more lonely.

Harold Mountjoy was another disappointment. After one letter: “Darling girl, forgive a scribbled note, but you are too precious to have brief letters. It would take a month to tell you all I feel about you, and I don’t have the time,” he didn’t write at Christmas or remember her birthday or even Valentine’s Day.

Finally, at the beginning of March, Helen decided she could bear her digs no longer. On the same day that her landlady used a cat-food-encrusted spoon to stir the beef stew with, and the tomcat invaded her room for the hundredth time and sprayed on her typewriter cover, she moved into Regina House, an all-female hostel in Hammersmith, which catered exclusively for visiting academics, and was at least clean and warm.

Nor was her job in publishing very exciting. The initial bliss of being paid to read all day soon palled because of the almost universal awfulness of the manuscripts submitted. To begin with, Helen wrote the authors polite letters of rejection, whereupon they all wrote back, sending her other unpublished works and pestering her to publish them; so finally she resorted, like everyone else, to rejection slips.

Her two bosses took very extended lunch hours and spent long weekends at their houses in the country. One of the director’s sons, having ignored her in the office, asked her out to dinner one evening and lunged so ferociously in the car going home that Helen was forced to slap his face. From then on he went back to ignoring her.

The only other unmarried man in the office was a science graduate in his late twenties named Nigel, a vegetarian with brushed-forward fawn hair, a straggly beard, a thin neck like a goose, and spectacles. For six months, Helen and he had been stepping round each other, she out of loneliness, and he out of desire. They had long political arguments and grumbled about their capitalist bosses. Nigel introduced her to Orwell and bombarded her with leftist literature.

He was also heavily involved with the anti-fox hunting movement and seemed to spend an exciting resistance life on weekends rescuing foxes and hares from ravening packs of hounds, harassing hunt balls with tear gas, and descending by helicopter into the middle of coursing meetings. He was constantly on the telephone to various cronies named Paul and Dave, arranging dead-of-night rendezvous to unblock earths. Often he came in on Monday with a black eye or bandaged wrist, after scuffles with hunt supporters.

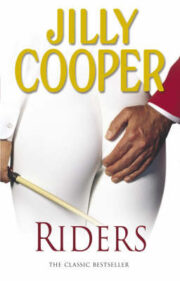

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.