When she found she had put her bag in the basin and washed her hands over it, she realized she was very tight. She couldn’t bear Jake to go away. She pressed her hot forehead against the mirror. “Gypsy Jake,” she murmured to herself.

Then it became plain that she must buy Africa. She had the money. Jake could pay her back, or she could be the owner and he the jockey. She had visions of herself in a big primrose yellow hat, leading Africa into the winner’s enclosure with two mounted policemen on either side. She was a bit hazy about what went on in show jumping. She looked in the telephone directory, but there was no Bobby Cotterel. He must be ex-directory; but the Mayhews had had the house before Bobby Cotterel. She spent ages finding the M’s. They did come after L, didn’t they? Oh God, the page was missing, No, it was the first number on the next page. Sir Edward Mayhew, Bandit’s Court. Her hand was shaking so much she could hardly dial the number.

“Hello,” said a brusque voice.

She was so surprised she couldn’t speak.

“If that’s burglars,” said the voice, “I’m here plus fifteen guard dogs and you can fuck off.”

Tory gasped. “No, it isn’t,” she said. “Is that Mr. Cotterel?” She must speak very slowly and try to sound businesslike.

Jake, having finished his glass of beer and ordered a large whisky, gazed at his reflection, framed by mahogany and surrounded by upside-down bottles in the mirror behind the bar. Totally without vanity, he looked in mirrors only for identity. He had spent too many Sundays at the children’s home, with scrubbed face and hair plastered down with water in the hope of charming some visitor into fostering or adopting him, to have any illusions about his attractiveness.

“Come here often?” said the barmaid, who worked in the pub on Sunday to boost her wages and in the hope of finding a new boyfriend.

“No,” said Jake.

He glanced at his watch. Tory had been away for nearly a quarter of an hour now. He hoped the stupid cow hadn’t passed out. He’d need a forklift truck to carry her home. He went out to look for her. She was standing by the telephone in the passage with her shoes off.

“That’s fine,” she was saying in a careful voice.

If Bobby Cotterel had not come back a week early from the South of France because it was so expensive, and been promptly faced with a large income-tax bill, he might not have been in such a receptive mood. Africa troubled his conscience, like his daughter’s guinea pig, whose cage, now she’d gone back to boarding school, needed cleaning out. He was not an unkind man. This girl sounded a “gent,” and was so anxious to buy Africa for four times the price he’d paid for her, and he wouldn’t have to pay any commission to Mrs. Wilton.

“The livery fee’s paid up for another three weeks,” he said.

“I’ll take that over,” said Tory.

“No, I’ll be happy to stand it to you, darling.”

“Can we come round and give you the check now?”

“Of course. Come and have a drink, but for Christ’s sake don’t tell anyone I’m back.”

Tory had had her first date, and been called darling and invited for a drink by Bobby Cotterel.

She turned towards Jake with shining eyes.

If she lost a couple of hundredweight, she’d be quite pretty, he thought sourly. What the hell had she got to look so cheerful about?

“You okay?”

“Wonderful. I’ve just bought Africa.”

“Whatever for? You don’t like horses.”

“For you, of course. You can pay me back slowly, a pound a week, or we can go into partnership. I’ll own her, you can ride her.”

A dull red flush had spread across Jake’s face.

“You’re crazy. How much did you pay?”

“I offered eight hundred and he accepted. He’s just had a bill for his income tax. I said we’d take the check around now, before Mrs. Wilton starts blabbing about Sir William and Malise Gordon.”

“Have you got that amount in the bank?”

“Oh, yes, I got £5,000 on my birthday, and lots of shares.”

“Your mother’ll bust a gut.”

“Hooray,” said Tory.

“She’ll say I got you plastered.”

“No, you did not. I did it all off my own bat, like those cricketers in the bar.”

She cannoned off a hatstand as she went out of the door.

Jake was finding it impossible to clamber out of the pit of despair so quickly. He might at least say thank you, thought Tory.

They walked to Bobby Cotterel’s house and handed over the check. Armed with a receipt, he walked her home, both of them following the white lines in the middle of the road. Half-shafts of moonlight found their way through the beech trees on either side of the road, shimmering on their dark gray-green trunks. Fortunately the house was still dark.

“Oh good,” said Tory, “I can put back Mummy’s mac before she finds out it’s missing. I’m going to London tomorrow. I’ve got two awful drinks’ parties, then a dance on Wednesday, but I’ll be home on Thursday. Mummy and Colonel Carter are going out to dinner. I’ve got to babysit. Perhaps you could come around, after they’ve gone out, and we can decide what to do.”

“I think it may be a bit more problematical than that,” said Jake.

He took the key, opened the door for her, and turned on the hall light. Oh God, thought Tory miserably, there was Fen’s whip lying on the hall table, beside a wilting bowl of pink peonies. Jake turned to her, a slight smile touching his lips. Was it contempt, or pity, or mockery?

“Thank you very much,” he said, and was gone.

Fighting back her disappointment that he hadn’t attempted to kiss her, Tory then reflected that she would probably have tasted of onion-flavored crisps.

5

The drinks’ parties on Monday and Tuesday were bad enough for Tory. But the dance on Wednesday was a nightmare. At the dinner party beforehand, some sadist had seated her next to Rupert Campbell-Black. On his right was a ravishing girl named Melanie Potter, whom all the girls were absolutely furious about. Melanie had upstaged everyone by turning up, several weeks after the season began, with a suntan acquired from a month in the Bahamas.

Rupert had arrived late, parking his filthy Rolls-Royce, with the blacked-out windows, across the pavement. He then demanded tomato ketchup in the middle of dinner, and proceeded to drench his sea trout with it, which everyone except his hostess and Tory thought wildly funny. Naturally he’d ignored Tory all the way through dinner. But there was something menacing about that broad black back and beautifully shaped blond head, a totally deceptive languor concealing the rampant sexuality. She wondered what he would have done if she’d tapped him on the shoulder and told him she was the owner of an £800 horse.

Then they went on to the dance and she somehow found herself piled into Rupert’s Rolls-Royce, driving through the laburnumand lilac-lined streets of Chelsea. She had to sit on some young boy’s knee, trying to put her feet on the ground and all her weight on them. But she still heard him complaining to Rupert afterwards that his legs were completely numb and about to drop off.

The hostess was kind, but too distraught about gate-crashers to introduce Tory to more than two young men, who both, as usual, danced one dance, then led her back and propped her against a pillar like an old umbrella, pretending they were just off to get her a drink or had to dance with their hostess. Thinking about Jake nonstop didn’t insulate her from the misery of it all. It made it almost worse. Obviously it was impossible that he should ever care for her. If no one else wanted her, why should he? Feeling about as desirable as a Christmas tree on Twelfth Night, she was sitting by herself at the edge of the ballroom when a handsome boy sauntered towards her. Reprieve at last.

“Excuse me,” he said.

“Oh, yes, please,” said Tory.

“If no one’s using this,” he said, “could I possibly borrow it?” and, picking up the chair beside her, he carried it back across the room and sat down on the edge of the yelling group around Rupert Campbell-Black. As soon as they got to the dance, Rupert had abandoned his dinner party and, taking Melanie, had gone off to get drunk with his inseparable chum, Billy Lloyd-Foxe, who was in another party. Now he was sitting, cigar drooping out of his handsome, curling mouth, wearing Melanie’s feather boa, while she sat on his knee, shrieking with laughter, with the pink rose from his buttonhole behind her ear.

Later Billy Lloyd-Foxe passed Tory on the way to the lavatory and on the way back, struck by conscience, asked her to dance. She liked Billy; everyone did; she liked his turned-down eyes and his broken nose and his air of life being a little bit too much for him. But everything was spoilt when Rupert and Melanie got onto the floor: Rupert, his blue eyes glittering, swinging Melanie’s boa round like the pantomime cat’s tail, had danced around behind Tory’s back, pulling faces and puffing out his cheeks to look fat like Tory and make Billy laugh.

Tory escaped to the loo, shaking. She found her dinner party hostess’s daughter repairing her makeup and chuntering with a couple of friends over the effrontery of Melanie Potter.

“Her mother did it on purpose. What chance have any of us got against a suntan like that? She turned up at the Patelys’ drinks’ party wearing jeans. Lady Surrey was absolutely livid.”

At that moment Melanie Potter walked in and went over to the mirror, where she examined a huge love bite on her shoulder and tried to cover it with powder.

“You haven’t got anything stronger, have you?” she asked Tory.

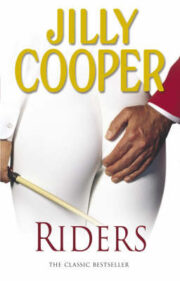

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.