Malise’s voice broke into his thoughts.

“Hope you don’t mind coming here again too much,” he said in an undertone. “I’m fond of this place, even if it is a bit quaint.”

Billy smiled. “Of course not.” That was all part of the act, to be cheerful, never to show the cracks in his heart.

He pointed to one of the more grotesque figures portrayed in the frieze round the walls of the bar.

“What did that poor chap do?”

“Raped Apollo’s mother. He was pegged down so that birds could peck continually at his liver.”

“Sounds like mine in the old days,” said Billy.

“Another Coke?” asked Malise.

“No, I’m fine.” Billy looked across at Griselda Hubbard, massive in a red track suit. What a disgustingly ugly pig she was, and already bad-mouthing poor little Fen.

“She’s a hopeless map-reader and kept making the most ridiculous fuss about stopping to graze and water the horses. If I’d listened to her we’d still be in France. Jake’s mad to let her ride the horses when she’s so soft. They’ll be walking all over her in a week or two, and she’s no sense of hierarchy, treats her groom like an equal, even a superior. She’ll have both her and the two horses tucked up in her hotel bedroom watching the telly at any minute.”

“I hope we can get English food here,” grumbled Driffield, brandishing an empty glass and looking around, hoping someone would buy him a drink.

Rupert was discussing declining television viewing figures with Malise. “They ought to sack Dudley; he’s such a pratt. What we need on the circuit is crumpet.”

“Who’s talking?” sneered Driffield.

“Not groupie crumpet, competing crumpet, some good-looking riders,”

“Like Lavinia,” said Malise.

“She was never good enough, or pretty enough,” said Rupert.

“Ahem,” said Billy.

“Anyway, she married a frog. I am talking about someone like Ann Moore or Marion Coakes; someone every little pony-mad girl can identify with. It’s the pony-mad girls that make up the audiences and bring in their parents.”

“What about Fenella Maxwell?” said Malise.

“Well, if she shed about a stone and a half, most of which is spots.”

“Thank you, Rupert,” said a shrill voice.

Everyone turned round.

“Mamma Mia,” said Billy.

“Christ,” said Rupert. “You have grown up.”

Fen stood staring at them, eyes widened like a faun, drained sea green shirt tucked into drained sea green Bermuda shorts, espadrilles on the end of her long smooth brown legs. Her spiky blond hair was still wet from the shower. Not a spot spoiled her smooth, brown cheeks, just a faint touch of blusher. She looked like a wary but very beautiful street urchin.

Oh, God, thought Malise, how am I going to chaperone that in Rome?

As it was very late, they went straight in to dinner. Ivor Braine and, amazingly, Driffield made concerted efforts to sit next to Fen. Ivor just crumbled Gristiks and gazed at her with his mouth open. All the team, except Griselda, who was obviously feeling upstaged, were incredibly nice, asking her about Jake’s leg and the horses and how the glamorous Sarah was settling in. The waiters, flashing teeth and menus, kept filling her glass with chianti. Not having touched a drop since she’d started dieting, she suddenly felt very light-headed.

“I’m starving,” she told Driffield. “I don’t think I could ever look at a grapefruit or a lettuce leaf again.”

“How much have you lost?”

“Not enough for Rupert.”

Across the table, Rupert laughed and raised his glass to her.

“I overestimated. You look delectable. Don’t lose an ounce more.”

“I’m going to have fettucine,” said Griselda sourly, “followed by abbacchio al forno.”

“What’s that?” said Ivor.

“Roast baby lamb, cooked whole,” said Griselda, watering at the mouth.

Probably one of those lambs that came over on the ferry, thought Fen savagely. Bloody carnivore. Suddenly she felt less hungry.

“What’s ucelletti?”

“Little songbirds roasted on a spit,” said Griselda. “They’re very good.”

“God, this is a barbaric country,” said Billy. “I’m surprised they don’t casserole all those stray cats hanging round the street.”

“Not enough meat on them,” said Rupert.

Next moment a messenger arrived at the table with two telegrams for Fen. One was from Jake and Tory and the children. When she opened the other, she gasped and went bright scarlet, but failed to shove it back into the envelope quickly enough to stop Driffield reading it.

“ ‘Congratulations,’ ” he read out, “ ‘and good luck. Look forward to seeing you this summer. Dino Ferranti.’ Consorting with the enemy, are we? You could do a lot worse for yourself. Evidently his father’s as rich as Croesus.”

“It’s nothing,” stammered Fen. “We just met briefly at the World Championship. I wonder how he discovered I’d been selected.”

Rupert was looking across at her with a dangerous glint in his eyes. “The sly fox,” he said, “must have been working overtime at Les Rivaux. As well as making a play for you, he was running like mad after Helen.”

“Not nearly as much as Macaulay was running after you,” began Driffield, then stopped when he saw the blaze of anger on Rupert’s face. “Sorry, dangerous subject.”

“Dino,” said Rupert, leaning over to fill up Fen’s glass, “even pursued Helen when we were in America. While she was staying with her mother, he was evidently never off the telephone, pestering her to go out with him.”

Fen felt her happiness evaporate. Seeing her face, Billy said quickly, “Never met Dino. Can’t imagine him pestering anyone. He sounds far too laid back.”

Dinner seemed to go on for hours. Fen found she couldn’t finish her spaghetti.

“Is Billy all right?” she said to Driffield in an undertone. “He seems to have lost all his sparkle and his hair’s even grayer than it was at Olympia.”

“Hasn’t really had a good win since then,” said Driffield. “Malise is only keeping him in the team for sentimental reasons.”

“He’s still so attractive.”

“Who is?” asked Rupert. Throughout dinner his eyes had flickered over Fen. He was the only man she’d ever met who could stare so calculatingly and without any embarrassment, as though he was a cat and she a bird’s nest he was going to raid in his own good time.

“No one,” she said quickly. She turned to Ivor. “Tell me about your new horse. Is he really called John?”

“I think you’ve lost your audience, Ivor,” said Rupert, five minutes later. Fen had fallen fast asleep, her head on the red raffia table mat.

39

Three days later, Fen had reached screaming pitch. The week had been one succession of disasters. She remembered Jake warning her that his first show with the British team had begun catastrophically, but nothing could have been as bad as this. She didn’t even dare ring him at the hospital.

On the first day, she’d entered Desdemona in a speed class for horses who had never jumped in Rome before. The little mare had gone like a whirlwind, treating the course with utter disdain, sailing over fences she couldn’t see over, whisking home in the fastest time by a couple of seconds. Fen was so enchanted by such brilliance she promptly jumped off and flung her arms around Desdemona’s neck, to the delight of the crowd.

The British team were less amused.

“You berk,” said Rupert, as starry-eyed she led Desdemona out of the ring, “you’ve just lost yourself a grand.”

“But she won,” gasped Fen.

“She may have done, but you disqualified her by dismounting before you left the ring.”

“Oh, my God,” said Fen. “Oh, Des, I’m sorry. I didn’t think. What on earth will Jake say?”

“Shouldn’t tell him. Least said, soonest sewn up,” said Ludwig cheerfully, who, as the new winner, rode grinning into the ring to collect his prize money.

In the big class later in the day Fen made two stupid mistakes, putting Macaulay out of the running. Then on the second day in the relay competition, because Rupert always paired with Billy and Ivor with Driffield, Fen was stuck with a reluctant Griselda.

“I’ll show her,” fumed Fen, waiting on Desdemona, holding her hand out ready for the baton, as Griselda cantered up to them after a clear and surprisingly swift round on Mr. Punch. Desdemona, however, had other ideas. Mr. Punch had nipped her sharply several times on the journey out and, at the sight of him thundering down on her, she jumped sharply out of his way, causing Fen to drop the baton.

“What dreadful language,” said Rupert, who was standing nearby, grinning from ear to ear. “What a good thing all those nice Italian spectators can’t understand what Griselda’s saying to Fen.”

Determined to redeem herself in the big class in the evening, Fen rode with such attack that when Macaulay decided he didn’t like the jump built in the shape of a Roman villa and started to dig his toes in, Fen shot straight over his head, covering herself in bruises.

The previous day, Malise had organized some sightseeing. They went to St. Peter’s and saw the statue of St. Peter, with the stone foot worn away by the kisses of the pilgrims.

“I came here with Janey,” Fen overheard Billy saying to Rupert. “I swore that by the end of our life together I’d have kissed her more than the pilgrims had kissed that foot. Perhaps that’s why she pushed off.” He was trying to make a joke of it, but Fen could sense his despair.

Being superstitious, all the riders wanted to visit the Trevi fountain.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” said Fen, admiring the bronze tritons, the gods and goddesses, the wild horses, and the leaping glistening, rushing cascade of water.

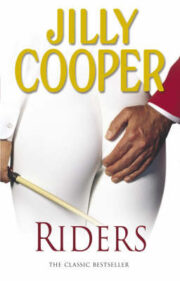

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.