“No, oh no!” wept Miss Taverner, laying her cheek against his shoulder. “It is only that I am so thankful!”

Chapter XXIII

If Miss Taverner expected to find her brother indignant at the treatment he had undergone she was soon informed of her mistake. He had had a capital time.

“Nothing could be like it!” he told her over and over again. “I must have a yacht of my own. If Worth won’t consent to it it will be the greatest shame imaginable! I am persuaded Harriet would like it above all things. I wish Worth had come here to-night, I cannot conceive why he should not. Evans—he is Worth’s captain, you know: a first-rate fellow!—Evans says I have a great aptitude. Never in the least sick—and we ran into a pretty groundswell on Tuesday, I can tell you! But it made no odds to me, never felt better in my life!”

“But Perry, when you awoke from that drug, were you not sadly alarmed?”

“No, why should I be? I had a devilish headache, but that soon went off, and then Evans gave me Worth’s letter.”

“What must your feelings have been when you read it! He told you the whole?”

“Oh yes, I was excessively shocked! But ever since he had the impudence to interfere over that duel I have not at all liked my cousin, you know.”

“But Perry, he did not interfere! It was he who—”

“Ay, so it was; I was forgetting. But it’s all one: I have been thinking him a shabby fellow these several months.”

“We have not valued Lord Worth’s protection as we should,” said Judith, colouring faintly. “If we had trusted him more, been upon kinder terms, perhaps he need not have put you away, or—”

“Lord, there’s nothing in that!” Peregrine declared. “I am precious glad he did, because I had never been to sea before in my life. I would not have missed it for the world! To own the truth, I did not above half like coming ashore again, except, of course, for seeing you and Harriet. However, I am quite determined to set up a yacht of my own, only it will cost a good deal, I daresay, and ten to one Worth won’t hear of it.”

“I wish,” said Miss Taverner, with some asperity, “that you would give your thoughts a more proper direction! Towards Lord Worth we must be all obligation. Without his protection I am very much disposed to think that you and I should have made but wretched work of everything.”

“It is very true, upon my honour! I assure you I am quite in charity with him. But then, you know, I never disliked him as much as you did, though he has often been amazingly disagreeable.”

Miss Taverner’s flush deepened. “Yes, at first I did dislike him. The circumstances of our—”

“Lord, I shall never forget the day we called in Cavendish Square, and found that it was he who was our guardian! You were as mad as fire!”

“It is a recollection that should be forgotten,” replied Miss Taverner. “Lord Worth’s manners are—are not always conciliating, but of the propriety of his motives we can never stand in doubt. We owe him a debt of gratitude, Perry.”

“I am very sensible of it. To be sure, we were completely taken in by my cousin. And to drug me, and put me aboard his yacht—Lord, I thought he was going to murder me when he forced that stuff down my throat!—was the neatest piece of work! I had no notion I should like being upon the sea so much! Evans was in a great pucker lest I should be angry at it, but, ‘Lord,’ I said, ‘you need not think I shall try to swim to shore! This is beyond anything great!’”

Miss Taverner sighed, and gave up the struggle. Peregrine continued to talk of his experiences at sea until it was time to go to bed. Miss Taverner could only be glad that since he had formed the intention of driving to Worthing upon the following day any further descriptions of ground-swells, squalls, wearing, luffing, squaring the yards, or reefing the sails must fall to Miss Fairford’s lot instead of hers. It was a melancholy reflection that although she would have been ready to swear, a day before, that she could not have borne to let him out of her sight again, if he should be restored to her, three hours of his company were enough to make her look forward with complaisance to his leaving her directly after breakfast next morning. Even when he was not recounting his adventures his conversation had a nautical flavour. He talked of crowding all sail to Worthing, of bringing to, and hauling his wind, and of making out a friend at cable’s length. An empty wine-bottle became a marine officer, landsmen on board a ship were live lumber, and a passer-by in the street was described as being as round as a nine-pounder. A number of sea-shanties being sung loudly and inaccurately all over the house finally alienated even Mrs. Scattergood’s sympathy, and by eleven o’clock on Thursday nothing could have exceeded both ladies’ anxious solicitude to set him on his way to Worthing.

Miss Taverner then sat down to await her guardian. He did not come. Only Captain Audley called in Marine Parade that morning, and when Miss Taverner asked, as carelessly as she could, whether his lordship was in Brighton, the Captain merely said: “Julian? Oh yes, he is here, but I fancy you won’t see him to-day. York arrived in Brighton yesterday, you know.”

Miss Taverner, who was inclined to rate her claims quite as high as the Duke of York’s said, “Indeed!” in a cold voice, and turned the subject.

There was no appearance of Worth at the ball that night, but upon Miss Taverner’s return to Marine Parade she found a note from him lying on the table in the hall. She broke the seal at once, and eagerly spread open the single sheet.

Old Steyne, June 25th, 1812.

Dear Miss Taverner—I shall do myself the honour of waiting on you tomorrow morning at noon, if this should be convenient to you, for the purpose of resigning into your charge the documents relating to your affairs with which I have been entrusted during the period of my guardianship. Yours, etc.,

Worth.

Miss Taverner read this missive with a sinking heart, and slowly folded it up again. Miss Scattergood, observing her downcast look, hoped that she had not had bad news. “Oh dear me, no!” said Miss Taverner.

Breakfast, upon the following morning, was enlivened by the appearance of Peregrine, who had driven back from Worthing so early on purpose to wish his sister many happy returns of her birthday. He thought himself a very good brother to have remembered the event, and would have bought her a present if Harriet had put him in mind of the date sooner. However, they would go out together after breakfast, and she should choose her own present, which would be a much better thing, after all. He admired the quilted parasol of shaded silk which Mrs. Scattergood had given Judith, and said there was no need to inquire who had sent her the huge bouquet of red roses which graced the table. “They come from Audley, I’ll be bound.”

“Yes,” agreed Miss Taverner, with a marked lack of enthusiasm. “I have had a letter from my uncle also. You may read it, if you choose. It is painful: one cannot but pity him. He seems to have known only part of what my cousin intended.”

“Oh well, don’t let us be thinking of him now!” said Peregrine. “We are very well rid of the pair of them. Only fancy, though! Worth told Sir Geoffrey the whole, when he saw him in town this week. Sir Geoffrey thinks Worth a very tolerable sort of a fellow.” He poured himself out a cup of coffee. “Now, what would you like to do today? You have only to give it a name; I am quite at your disposal. Shall we drive over to Lewes? I believe there is a castle, or some such thing, to be seen there.”

“Thank you, Perry,” she said, touched by this handsome offer. “But Lord Worth is coming to see me this morning. I was thinking that you should stay at home with me. You will want to thank him for all that he has done.”

“Oh, certainly!” said Peregrine. “I shall be very glad to meet him, to be sure. I want to talk to him about my yacht, you know.”

Shortly before noon Peregrine, who was seated in the window of the drawing-room, quizzing the passers-by, announced that Worth was approaching. “My dear Ju,” he said in tones of awe, “only look at the coat he is wearing! I wonder whether Weston made it? Do but look at the set of it across the shoulder!”

Miss Taverner declined leaning out of the window to stare at his lordship, and begged her brother to draw in his head. Instead of doing anything of the kind Peregrine waved to attract Worth’s attention, and, upon the Earl looking up, was instantly struck by the exquisite arrangement of his cravat. He turned, and said impressively: “I do not care if he does give me one of his set-downs; I must know how he ties his cravat!”

The Earl had knocked on the door by this time, and in a few moments his step was heard on the stairs. Peregrine went out to meet him. “Come up, sir! We are both here!” he said. “How do you do? You are the most complete hand indeed, you know! My head, when I awoke! My mouth too! There was never anything like it!”

“Was it very bad?” inquired the Earl, leisurely mounting the last three stairs.

“Oh, beyond anything! But I don’t mean to complain; I have had a famous time of it! But come into the drawing-room! My sister is there, and I have something very particular to say to you. Ju, here is Lord Worth.”

Miss Taverner, who, for reasons best known to herself, had suddenly become absorbed in her embroidery, laid aside the frame and got up. She shook hands with the Earl, but before she could speak Peregrine was off again.

“I wish you would tell me, sir, what you call that way of tying your cravat! It is devilish natty!”

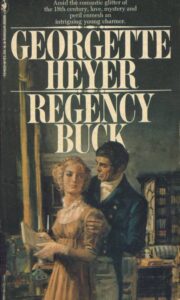

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.