“His illness in your house!” Miss Taverner cried. “That cough! Good God, is this possible?”

“Oh yes,” said the Earl in his matter-of-fact way. “Scented snuffs have long been a means of poisoning people. You may remember, Miss Taverner, that I found an excuse to send Hinkson up to Brook Street while you were at Worth?”

“Yes,” she said. “You wanted the lease of the house.”

“Not at all. I wanted the rest of Peregrine’s snuff. He had told me where the jar was kept, and Hinkson was easily able to find an opportunity to go up to his dressing-room and exchange the jar for another, similar one, that I had given him. Later, when I was in town again, I visited the principal snuff-shops in the whole of London—a wearing task, but one which repaid me. That particular mixture is not a common one; during the month of December only three four-pound jars of it were sold in town. One was bought at Fribourg and Treyer’s by Lord Edward Bentinck; one was sold by Wishart to the Duke of Sussex; and the third was sold by Pontet, in Pall Mall, to a gentleman who paid for it on the spot, and took it away with him, leaving no name. The description of that gentleman with which the shopman was obliging enough to furnish me was exact enough not only to satisfy me, but also to embolden me to suppose that he would have no great difficulty in recognizing his customer again at need. Do you think a jury would be interested in that, Mr. Taverner?”

Bernard Taverner was still clenching the edge of the mantelpiece. A rather ghastly smile parted his lips. “Interested—but not convinced, Lord Worth.”

“Very well,” said the Earl. “We must pass on then to your next and last attempt. I will do you the justice to say that I don’t think it was one you would have made had not the fixed date of Peregrine’s marriage made it imperative for you to get rid of him at once. You were hard-pressed, Mr. Taverner, and a little too desperate to consider whether I might not be taking a hand in the affair. From the moment of Peregrine’s wedding-day being made known you have not made one movement out of your lodgings that has not been at once reported to me. You suspected Hinkson, but Hinkson was not the person who shadowed you. You have had on your heels a far more noted figure, one who must be as well known as I am myself. You have even thrown him a shilling for holding your horse. Don’t you know my tiger when you see him, Mr. Taverner?”

Bernard Taverner’s eyes were fixed on the Earl’s face. He swallowed once, but said nothing.

The Earl took a pinch of snuff. “On the whole,” he said reflectively, “I believe Henry enjoyed the task. It was a little beneath his dignity, but he is extremely attached to me, Mr. Taverner—a far more reliable tool, I assure you, than any of your not very efficient hirelings—and he obeyed me implicitly in not letting you out of his sight. You would be surprised at his resourcefulness. When you drove your gig over to New Shoreham to strike a bargain with that seafaring friend of yours you took Henry with you, curled up in the boot. His description of that mode of travel is profane but very graphic. I am anticipating, however. Your first action was to introduce a creature of your own into Peregrine’s household—a somewhat foolhardy proceeding, if I may say so. It would have been wiser to have risked coming into the foreground at that juncture, my dear sir. You should have disposed of Peregrine yourself. Well, you made arrangements to have Peregrine transported out to sea. Was he then to be dropped overboard? It would be interesting to know what precise fate lay in store for him. I can only trust that it may have befallen Tyler, whose task was undoubtedly to have overpowered Peregrine at a convenient moment during his drive to Worthing, and to have handed him over to the captain of that vessel. To make doubly sure, Tyler tried to drink Hinkson under the table before setting out. But Hinkson has a harder head than you would believe possible, and instead of remaining under the table, he came to me. I waylaid Peregrine on the West Cliff, and requested him to come back with me to my house on a matter of business. Once I had him under my roof I gave him drugged wine to drink, while Henry performed the same office for Tyler. Hinkson then drove Tyler to the rendezvous you had appointed, Mr. Taverner, and delivered him up to your engaging friends. It was he who wrote you the message which you thought came from Tyler, telling you that he had done his part, and would meet you in London. Peregrine was carried out of my house that evening and taken aboard my yacht, which was lying in New Shoreham harbour.”

“Oh, how could you?” Judith broke in. “What he must have suffered!”

He smiled. “Charles felt very much as you appear to do, Miss Taverner. Fortunately I am not so tender-hearted. Peregrine has suffered nothing worse than a severe headache, and a week’s cruise in excellent weather. He has not been imagining himself in any danger, for I gave my captain a letter of explanation to be delivered to him when he came to his senses.”

“You might have told me!” Judith said.

“I might, had I not had an ardent desire to try your cousin into betraying himself,” replied the Earl coolly. “It was with that object that I left Brighton. Charles did the rest. He led Mr. Bernard Taverner to believe—did he not, my dear sir?—that he and I had concocted a scheme to lure you to town, and there to force you into marriage with one or other of us. He dropped a special licence under Mr. Taverner’s nose and left the rest to his own ingenuity. You took fright, sir, precisely as you were meant to, and this is the outcome. The game is up!”

“But—but you?” demanded Miss Taverner, in a bewildered voice. “Where were you, Lord Worth? How could you know that my cousin meant to bring me here?”

“I did not know. But when Henry was able to report to Charles that your cousin had left Brighton on Saturday night, Charles sent the tidings to me express, and I returned to Brighton on Sunday night, where I have been ever since, waiting for your cousin to move. Henry followed you to the Post Office this morning, witnessed your meeting with Mr. Taverner, and ran to tell me of it. I could have overtaken you at any moment during your drive here had I wanted to.”

“Oh, it was not fair!” exclaimed Miss Taverner indignantly. “You should have told me! I am very grateful to you for all the rest, but this—!” She got up from her chair, rather flushed, and glanced towards her cousin. He was still standing before the fireplace, his face rigid, and almost bloodless. She shuddered. “I trusted you!” she said. “All the time you were trying to murder Perry I believed you to be our friend. My uncle I did suspect, but you never!”

He said in a constricted voice: “Whatever I may have done, my father had no hand in. I admit nothing. Arrest me, if you choose. Lord Worth has yet to prove his accusations.”

Her mouth trembled. “I cannot answer you. Your kindness, your professions of regard for me—all false! Oh, it is horrible!”

“My regard for you at least was not false!” he said hoarsely. “That was so real, grew to be so—But it does not signify talking!”

“If you stood in such desperate need of money,” she said haltingly, “could you not have told us? We should have been so happy to have assisted you out of your difficulties!”

He winced at that, but the Earl said in his most damping tone: “Possibly, but it is conceivable that I might have had something to say to that, my ward. Nor do I imagine that with a fortune of twelve thousand pounds a year to tempt him Mr. Taverner would have been satisfied with becoming your pensioner. May I suggest that you leave this matter in my hands now, Miss Taverner? You have nothing further to fear from your cousin, and you cannot profitably continue this discussion. You will find that the chaise that is to convey you back to Brighton has arrived by now. I want you to go out to it, and to leave me to wind up this affair in my own way.”

She looked up at him doubtfully. “You are not going to come with me?” she asked.

“I must ask you to excuse me, Miss Taverner. I have still something to do here.”

She let him lead her to the door, but as he opened it, and would have bowed her out, she laid her hand on his arm, and said under her breath: “I don’t want him to be arrested!”

“You may safely leave everything to me, Miss Taverner. There will be no scandal.”

She cast a glance at her cousin, and looked up again at the Earl. “Very well. I—I will go. But I—I don’t want you to be hurt, Lord Worth!”

He smiled rather grimly. “You need not be alarmed, my child. I shan’t be.”

“But—”

“Go, Miss Taverner,” he said quietly.

Miss Taverner, recognizing the note of finality in his voice, obeyed him.

She found that a chaise-and-four, with the Earl’s crest on the panels, was waiting for her outside the cottage. She got into it, and sank back against the cushions. It moved forward, and closing her eyes, Miss Taverner gave herself up to reflection. The events of the past hours, the shock of finding her cousin to be a villain, could not soon be recovered from. The drive to Brighton, which had seemed so interminable earlier in the day, was now too short to allow her sufficient time to compose her thoughts. These were in confusion; it would be many hours before she could be calm again, many hours before her mind would be capable of receiving other and happier impressions.

The chaise bore her smoothly to Brighton, and she found Peregrine awaiting her in Marine Parade. She threw herself into his arms, her overcharged spirits finding relief in a burst of tears. “Oh, Perry, Perry, how brown you look!” she sobbed.

“Well, there is nothing to cry about in that, is there?” asked Peregrine, considerably surprised.

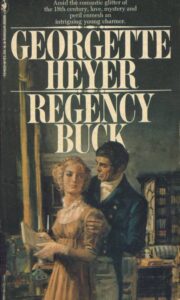

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.