"I'm leaving all my friends. It takes years to make good friends, and now they're gone."

"If they were such good friends, how come not one came by to say goodbye to you?" I asked.

"They're just angry about it," she replied.

"Too angry to say goodbye?"

"Yes," she snapped. "Besides, I spoke to everyone on the telephone last night."

"Since your accident, Gisselle, most of them hardly have anything to do with you. There's no sense in pretending. They're what are known as fair-weather friends."

"Ruby's right, honey," Daddy said.

"Ruby's right," Gisselle mimicked. "Ruby's always right," she muttered under her breath.

When Lake Pontchartrain came into view, I gazed out at the sailboats that seemed painted on the water and thought about Uncle Jean and Daddy's confession that what was thought to have been a horrible boating accident was really something Daddy had done deliberately in a moment of jealous rage. He had spent every day since and would continue to spend every day hereafter regretting his action and suffering under the weight of the guilt. But now that I had lived with Daddy and Daphne for months, I felt certain that what had happened between him and Uncle Jean was primarily Daphne's fault and not Daddy's. Perhaps that was another reason why she wanted me out of sight. She knew that whenever I looked at her, I saw her for what she was: deceitful and cunning.

"You two are going to enjoy attending school in Baton Rouge," Daddy said, flicking a gaze at us in his rearview mirror.

"I hate Baton Rouge," Gisselle replied quickly.

"You were really there only once, honey," Daddy told her. "When I took you and Daphne there for my meeting with the government officials. I'm surprised you remember any of it. You were only about six or seven."

"I remember. I remember I couldn't wait to go home."

"Well now you'll learn more about our capital city and appreciate what's there for you. I'm sure the school will have excursions to the government buildings, the museums, the zoo. You know what the name 'Baton Rouge' means, don't you?" he asked.

"In French it means 'red stick'," I said.

Gisselle glared. "I knew that too. I just didn't say it as quickly as she did," she told Daddy.

"Oui, but do you know why it's called that?" I didn't and Gisselle certainly had no idea, nor did she care. "The name refers to a tall cypress tree stripped of its bark and draped with freshly killed animals that marked the boundary between the hunting grounds of the two Indian tribes at the time," he explained.

"Peachy," Gisselle said. "Freshly killed animals, ugh."

"It's our second-largest city and one of the country's largest ports."

"Full of oil smoke," Gisselle said.

"Well, the hundred miles or so of coastline to New Orleans is known as the Petrochemical Gold Coast, but it's not just oil up here. There are great sugar plantations too. It's also called the Sugar Bowl of America."

"Now we don't have to attend history class," Gisselle said.

Daddy frowned. It seemed he could do nothing to cheer her up. He looked at me and I winked, which made him smile.

"How did you find this school anyway?" she suddenly inquired. "Why couldn't you find one closer to New Orleans?"

"Daphne is the one who found it, actually. She keeps up on this sort of thing. It's a highly respected school and it's been around for a long time, with a long tradition of excellence. It's financed through donations and tuition from wealthy Louisianans, but mainly from an endowment granted to it from the Clairborne family through its sole surviving member, Edith Dilliard Clairborne."

"I bet she's a dried-up hundred-year-old relic," Gisselle said.

"She's about seventy. Her niece Martha Ironwood is the chief administrator. What you would call the principal. So you see, you're right in what we call the rich old Southern tradition," Daddy said proudly.

"It's a school without boys," Gisselle said. "We might as well check into a nunnery."

Daddy roared with laughter. "I'm sure it's nothing like that, honey. You'll see."

"I can't wait. This is such a long, boring ride. Put on the radio at least," Gisselle demanded. "And not one of those stations that play that Cajun music. Get the top forties," she ordered.

Daddy did so, but instead of brightening her outlook it lulled her to sleep, and for the remainder of the trip, Daddy and I had some quiet conversations. I loved it when he was willing to tell me about his trips to the bayou and his romance with my mother.

"I made a lot of promises to her that I couldn't keep," he said regretfully, "but one promise I will keep: I will see that you and Gisselle have the best of everything, especially the best opportunities. Of course," he added, smiling, "I didn't know you existed. I've always thought your arrival in New Orleans was a miracle I didn't deserve. No matter what's happened since," he added pointedly.

How I had come to love him, I thought as my eyes watered with happy tears. It was something Gisselle couldn't understand. More than once she had tried to get me to hate our father. I thought it was because she was jealous of the relationship that had quickly developed between us. But she was forever reminding me that he had deserted my mother in the bayou after he had made her pregnant while he was married to Daphne. Then he compounded his sins by agreeing to let his father purchase the baby.

"What kind of a man does such a thing?" she would ask, stabbing at me with her questions and accusations.

"People make mistakes when they're young, Gisselle."

"Don't believe it. Men know what they're doing and what they want from us," she'd said with her eyes small, the look cynical.

"He's been sorry about it ever since," I had said. "And he's trying to do what he can to make up for it. If you love him, you will do whatever you can to make his suffering less."

"I am," she'd said joyfully. "I help him by getting him to buy me whatever I want whenever I want it."

She's incorrigible, I thought. Not even Nina and one of her voodoo queens could recite a chant or find a powder to change her. But someday, something would. I felt sure of that; I just didn't know what it would be or when.

"There's Baton Rouge ahead," Daddy announced some time later. The spires of the capitol building loomed above the trees in the downtown area. I saw the huge oil refineries and aluminum plants along the east bank of the Mississippi. "The school is higher up, so you'll have a great view."

Gisselle woke up when he turned off the Interstate and took the side roads, passing a number of impressive-looking antebellum homes that had been restored: two-story mansions with columns. We passed one beautiful home that had Tiffany glass windows and a bench swing on the lower galerie. Two little girls were on it, both with golden brown pigtails and dressed in identical pink dresses and black leather saddle shoes. I imagined they were sisters, and my mind started to create a fantasy in which I saw myself and Gisselle growing up together in such a home with Daddy and our real mother. How different it all could have been.

"Just a little farther," Daddy said and nodded toward a hill. When he made another turn, the school came into view. First we saw the large iron letters spelling out the word GREENWOOD over the main entrance, which consisted of two square stone columns. A wrought-iron fence ran for what looked like acres to the right and to the left. I saw some buttonbush along the foot of the fence, its dark green leaves gleaming around the little white balls of white. Along a good deal of the fence were vines of trumpet creepers with orange blossoms.

From both sides of our car we could see rolling green lawns and tall red oak, hickory, and magnolia trees. Gray squirrels leapt gracefully from branch to branch as if they could fly. I saw a red woodpecker pause on a branch to look our way. There were stone walkways with short hedges and fountains everywhere, some with little stone statues of squirrels, rabbits, and birds.

An enormous garden led to the main building--rows and rows of flowers, tulips, geraniums, irises, golden trumpet roses, and tons of white, pink, and red impatiens. Everything looked trimmed and manicured. The grass was so perfect it looked cut by an army of grounds workers armed with scissors. Not a branch, not a leaf, nothing appeared out of place. It was as if we had ventured into a painting.

Above us the main building loomed. It was a two-story structure of antique brick and gray-painted wood. Dark green ivy vines worked their way up around the brick to frame the large panel windows. A wide stone stairway led up to the large portico and great front doors. There was a parking lot to the right with signs that read RESERVED FOR FACULTY and RESERVED FOR VISITORS. Right now the lot was nearly full of cars. There were parents and young girls meeting and greeting each other, old friends obviously renewing friendships. It was an explosion of excitement. The air was full of laughter, the faces full of smiles. Girls hugged and kissed each other, and all began talking at once.

Daddy found a spot for us and the van, but Gisselle was ready to pounce with a complaint.

"We're too far from the front, and how am I supposed to get up that stairway every day? This is horrible."

"Just hold on," Daddy said. "They told me there is an approach built for people in wheelchairs."

"Great. I'm probably the only one. Everyone will watch me being wheeled up every morning."

"There must be other handicapped girls here, Gisselle. They wouldn't build an entryway just for you," I assured her, but she just sat there scowling at the scene unfolding before us.

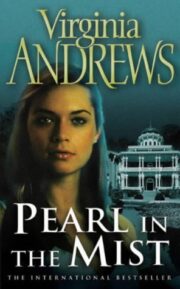

"Pearl in the Mist" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pearl in the Mist". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pearl in the Mist" друзьям в соцсетях.