"Look. Everyone knows everyone else. We're probably the only strangers at the school."

"Nonsense," Daddy said. "There's a freshman class, isn't there?"

"We're not freshmen. We're seniors," she reminded him curtly.

"Let me go find out how to proceed first," Daddy said, opening his door.

"Proceed home, that's how," Gisselle quipped. Daddy waved to our van driver, who pulled up alongside our car. Then he went to speak to a woman in a green skirt and jacket who was holding a clipboard.

"All right," Daddy said, returning. "This is going to be easy. The gangway is off right there. First you go to registration, which is being held in the main lobby, and then we'll go to the dormitory."

"Why don't we go to the dormitory first?" Gisselle demanded. "I'm tired."

"I was told to bring you here first, honey, so you can get your information packet about your classes, a map of the grounds, that sort of thing."

"I don't need a map of the grounds. I'll be in my room all the time, I'm sure," Gisselle said.

"Oh, I'm sure you won't," Daddy replied. "I'll get your chair out, Gisselle."

She pressed her lips together and sat back with her arms folded tightly under her bosom. I got out. The sky was crystalline blue and the clouds were puffy and full, looking like cotton candy. There was a magnificent view of the city below and beyond, a view of the Mississippi River with its barges and boats moving up and down. I felt like we were on top of the world.

Daddy helped Gisselle into her chair. She was stiff and uncooperative, forcing him to literally lift her. When she was situated in it, he started to wheel her toward the gangway. Gisselle kept her gaze ahead, her face twisted in a smirk of disapproval. Girls smiled at us and some said hello, but Gisselle pretended not to see or hear.

The gangway took us through a side entrance into the wide main lobby. It had marble floors and a high ceiling, with great chandeliers and a large tapestry depicting a sugar plantation on the far-right wall. The lobby was so large the voices of the girls echoed in it. They were all standing in three long lines, which line they were in depending on the first initial of their last names. The moment Gisselle set eyes on the crowd, she moaned.

"I can't sit here like this and wait," she complained loudly enough for a number of girls nearby to overhear. "We don't have to do this at our school in New Orleans! I thought you said they knew about me and would take my problems into consideration."

"Just a minute," Daddy said softly. Then he went to speak to a tall thin man in a suit and tie who was directing the girls into the proper lines and helping them to fill out some forms. He looked our way after Daddy spoke to him, and a moment later he and Daddy went to the desk upon which was the sign A-H. Daddy spoke to the teacher behind our desk, and she then gave him two packets. He thanked her and the tall man and quickly returned to our side.

"Okay," Daddy said, "I've got your registration folders. You're both assigned to the Louella Clairborne House."

"What kind of name for a dorm is that?" Gisselle said.

"It was named after Mr. Clairborne's mother. There are three dorms, and Daphne assured me that you two are in the best of the three."

"Great."

"Thank you, Daddy," I said, taking my packet from him. I felt guilty getting the preferential treatment along with Gisselle and avoided the jealous gazes of the other girls who were still waiting in line.

"Here's your packet," Daddy said. He put it into Gisselle's lap when she didn't reach for it. Then he turned her around and wheeled her out of the building.

"They told me there's an elevator to get you up and down in the main building. The bathrooms all have facilities for handicapped people, and your classes are all pretty much on the same floors so you won't have great difficulty getting from one to the other in time," Daddy said.

Reluctantly, Gisselle opened the packet as we descended the gangway. On the first page was a letter of welcome from Mrs. Ironwood, strongly advising that we read each and every page of the orientation materials and concern ourselves especially with the rules.

Two of the dormitories were located in the rear and to the right and the third dorm, our dorm, was located in the rear to the left. As we drove slowly around the main building toward our dorm, I gazed down the slope and saw the boathouse and the lake. A solid layer of water hyacinth stretched from bank to bank, their lavender blossoms pale with a dab of yellow on the center petals, surrounded by light green leaves. The water of the lake shone like a polished coin.

To our left, directly behind the building, were the playing fields.

"What beautiful grounds," Daddy said. "And so well looked after."

"This is like being in a prison," Gisselle retorted. "You have to go miles to find civilization. We're trapped."

"Oh, nonsense. There will be plenty for you to do. You won't be bored, I assure you," Daddy insisted.

Gisselle fell into her sulk as our dorm came into view. Structured like an old plantation house, the Louella Clairborne dorm was almost hidden from view by the large oaks and willow trees that spread their branches freely in front. It was a building constructed out of cypress, and it had upper and lower galeries enclosed with balustrades and supported by square columns that reached to the gabled roof. As we drove up, the gangway, built on the side of the front galerie, came into view. I didn't want to say it, but it did look like it had been especially made for Gisselle.

"Okay," Daddy said. "Let's get you two settled in. I'll go tell the dorm mother we're here. Her name's Mrs. Penny."

"That's all she's worth, probably," Gisselle quipped, laughing at her own sarcasm. Daddy went up the front steps quickly and disappeared within.

"You're going to have to push me all the way from this place every day to the classes, you know," Gisselle threatened.

"You can roll yourself along easily, Gisselle. The walkway looks smooth."

"It's too far!" she cried. "I'd be exhausted by the time I arrived."

"If you need to be pushed, I'll push you," I assured her with a sigh.

"This is so stupid," she said, folding her arms tightly under her breasts and glaring at the front of the dorm. Moments later Daddy appeared with Mrs. Penny, a short, plump woman with gray hair woven around her head in thick braids. She wore a bright blue and white dress over her stout body. When she drew closer, I saw she had innocent blue eyes, a jolly, wide smile with thick lips, and cheeks that ballooned to swallow up her small nose. She clapped her hands together as I stepped out of the car.

"Welcome, dear. Welcome to Greenwood. I'm Mrs. Penny." She extended her small hand with its thick, stubby fingers, and I shook it.

"Thank you," I said.

"You're Gisselle?"

"No, I'm Ruby. That's my sister, Gisselle."

"Great, she doesn't even know which is which," Gisselle muttered from within. If Mrs. Penny heard her, she didn't let on.

"This is so wonderful. You two are my first set of twins ever, and I've been dorm mother at the Louella Clairborne House for over twenty years. Hello, dear," she said, leaning over to look into the car at Gisselle.

"I hope we have a room on the ground floor," Gisselle snapped.

"Oh, of course you do, dear. You're in the first quad, the A quad."

"Quad?"

"Our rooms are designed around a central study area. Four bedrooms share two bathrooms and the sitting room," Mrs. Penny explained. "All of the other girls, except one new girl," she added, her smile flicking off and then on again, "are already here. They're all seniors like you two. They can't wait to meet you."

"And we're just dying to meet them," Gisselle sang sarcastically as Daddy brought her chair around again. He helped her into it and we headed for the house.

The dorm had a large front parlor with two large sofas and four high-backed cushion chairs around a pair of long, dark wood tables. There were standing lamps beside the sofas and chairs and standing lamps, chairs, and smaller tables in the corners. In one corner a small settee and another high-backed chair faced a television set. All the windows in the room had white cotton curtains and light blue drapes, and the hardwood floor had a large blue oval rug under and around the sofas. An enormous portrait of an elegant-looking older woman adorned the rear wall. It was the only painting in the room.

"That's a picture of Mrs. Edith Dilliard Clairborne," Mrs. Penny said in a reverent voice and nodded. "When she was a lot younger, of course," she added.

"She looks old there," Gisselle said. "What does she look like now?"

Mrs. Penny didn't respond. She continued her description of the house instead.

"The kitchen is at the rear," she said. "We have set times for breakfast and dinner, but you can always get a snack when you want. I try to run the house as if we're one big happy family," she told Daddy. Then she looked down at Gisselle. "I'll take you for a tour once you're settled in. Your quad is right this way," she added, indicating the corridor on our right. "First we'll show you where you're at, and then we'll get your things in. How was your ride from New Orleans?"

"Nice," Daddy said.

"Boring," Gisselle added, but Mrs. Penny ignored her and never changed her smile. It was as if she couldn't hear or see anything unpleasant.

Along the walls of the short corridor were hung oil paintings of New Orleans street scenes interspersed with portraits of people I imagined to be descendants of the Clairbornes. The hall was lit by two hanging chandeliers. At the end of it was the sitting room Mrs. Penny had described: a small room crowded with two pairs of cushioned chairs like the ones in the main lobby, an oval dark pine wood table, four desks at the rear, and standing lamps.

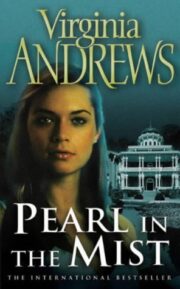

"Pearl in the Mist" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pearl in the Mist". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pearl in the Mist" друзьям в соцсетях.