I close my eyes. “What did she say?” I ask, trying to keep him talking.

“The same thing everyone says before they die. ‘No.’ ‘Please.’ ‘Stop.’” He scoffs. “It’s all so disappointing and boring—before that, though . . . before that, she lied. Once I started dragging her, she told me she liked me. But then she tried to run.”

I pretend he isn’t talking about Ruth. “It sounds like she had it coming, Ralph.” I remind myself that the excruciating pain in my leg is evidence that I’m alive. “I get it.”

“Yeah.” He nods. “I was polite—I asked, you know—I wanted permission. Weeks earlier I’d said, ‘Ruth, let’s hang out maybe,’ and Ruth goes, ‘Sure, Ralph, sure. Whatever.’ So instead of making plans, which is so formal in my opinion, I meet her halfway the night I know she’s coming to your house, right?”

“Right, of course.”

“And I just want her to talk to me, you know? But even though she’d already promised me, once I’m actually standing there she changes her mind—looks at me like I’m special needs. Tells me to back off. And that’s when I realized she was just a scarecrow—a fake person. A fucking cunt.” If they don’t get here soon, there won’t be any evidence that I was ever here. “Can you believe that, Kippy? I’d had it, you know, just had it. So I grabbed her and shook her and finally she started listening.”

“That’s smart,” I whisper. I have to buy time. “I mean you had to punish her, right?”

His lazy eye rolls. “I wasn’t even planning to cut her open, you know. It was only when she was hanging there that I thought, Maybe I should see what she looks like on the inside.” His eyes change. He’s heard the sirens. He looks toward the window and looks back at me, silent.

I give him my most pleading look, and even try to smile. “Remember when your parents brushed my hair?” I whisper. Outside the windows, the sky goes yellow with lightning. “Ralph, please. I want to stay.” For a second he searches my face, his eyes bright with what I think is love. Then he grabs me by the hair, and slams my head against the wall, over and over, mimicking the way I just said, “Please.”

The ringing in my ears is a welcome distraction from my leg, and I am thinking about how much Dom will suffer if I am gone, and how he will never be all right again, and isn’t that the saddest part about this? It seems strange to be thinking so clearly while someone is trying to murder you—to not be able to fight back even though you thought you were the kind of person who would. Ruth and I both held stock-still before we died. She wouldn’t move, and I couldn’t.

“You stupid girl,” Ralph mutters. “You know for a brief moment I wanted you to catch me. It seemed such a pity for someone else to be taking credit.” There’s blood in my eyes, but I can hear him opening the door to the basement, and I know this is it, that no one will find me—that Ralph will find a way to make excuses. And as the world around me gets fuzzy, fading to a bluish black that is speckled with stars, I am pretty sure I hear the sound of breaking glass and Davey’s voice, calling for me through the dark.

BIG GAME

The images come in bursts, like flashes from a strobe light.

I am on my side, on the floor, prying open one bruised eye with tired fingers, and there is Ralph, swinging at Davey’s head with a large frame yanked from the wall. (Is it a family photo? One of the staged glamour shots the Johnstons did every spring?) Glass from the frame shatters on the carpet, but instead of falling, Davey kicks Ralph in the stomach, sending him tumbling back on top of me.

“Get the fuck off her!” Davey shouts, grabbing Ralph by the hair and dragging him away. “Hold on, Kippy, I’m coming—stay awake—force yourself to stay awake.”

“You’re alive,” I whisper. I hear Ralph screaming. Keep him alive, too, I am thinking, we need them to arrest him. My fingers are falling asleep and so am I, but then I can feel myself being lifted and Davey whispering in my ear, “Be okay. Hold on.”

The sirens are right outside and I manage to put my arms around his neck. “Your leg,” he says. I look over his shoulder and see Ralph hanging upside down in his sleeping bag from one of the ceiling beams, shouting at us. Davey puts his lips against my forehead and explains to me that it’s some kind of special-ops maneuver.

“You’re so cool,” I keep murmuring, and I am waking up to the pain of my leg—I am always waking up lately. And even though I am covered in blood, and mud, and vomit, and urine, Davey holds me. Even when the cops come storming through the broken front door and Dom is running toward us across the yard, screaming my name, he doesn’t put me down.

HUNTING PARTY

Apparently Ralph confessed loudly and proudly from his upside-down position, his face deep orange from a combination of gravity and bear spray, admitting to the cops what he’d done and how he’d planted straw and stuff in Colt’s truck. How Ruth teased him and deserved it. How Mrs. Klitch was dispensable. All of it.

Davey didn’t even know that I was really conscious during any of this, because he’s got his head on my belly now, retelling me everything in low tones.

“It was so hard not to kill him,” he says over and over. “I knew exactly how to do it. And I’d been trained to do it. And nobody would have faulted me for it.” The machines around my metal bed are beeping sleepily. “But I didn’t.” Dom will be back from the cafeteria soon with ginger ale and candy. “Before I knew what he did to Ruth—when I saw him hurting you—I wanted to kill him.” Davey squeezes my waist.

“I’m proud of you,” I say. He’s not fishing for compliments or saying explicitly that he managed to control himself—and he’s not saying he trusts his brain again—but that’s because he’s Davey and he’s a boy, and I guess also because he trusts me to read him, which I can now, I think.

I stroke his hair. “I told you you’re not crazy.” It hurts my head to smile. “I’m so glad you’re okay.”

Davey sits up and searches my face, and I’m suddenly self-conscious about the bandage on my head. “Just so you know, I wasn’t ever mad at you,” he says. “Unfortunately I don’t think you could ever do anything to change my feelings about you.” He puts his thumb on my lips.

Forgiveness feels like hope and like a challenge. “I won’t push it,” I say.

Davey had to leave for a little bit and clean up his house. His parents are coming home early now that Ralph has been arrested. He printed off the latest email for me:

Davey, honey,

Optimism and closure feel delicate but have arrived. How do you feel? Your father is crying, obviously. I am cracking jokes. FART has been good for both of us.

We want you to know we are certainly real jerks for up and leaving you. . . . All I can say is it seemed like the right thing at the time. Please forgive us. Everything is so fluid and tenuous. All I mean to say is we will grapple with the future as a family. We love you.

Kippy deserves a medal. We cannot bring ourselves to call her for various reasons. She became over the last decade a member of the family, but even more than you, she is a reminder of what we lost. We would like to thank her but it feels too much. . . . Please find a way to convey this for us.

Your mother

I asked him why the cross-outs, and he said he didn’t want me to not believe what he’d said about how his parents had disparaged his severed-finger, but he changed his mind. He explained what the sentences said. “They were pissed at first,” he insisted. “And it wasn’t about Ruth, it was about the fact that I’d fucked up.” I told him that maybe the point of being close like this was just to believe each other, period.

“I guess it’s also gonna be tough, them wanting to talk about feelings and work shit out constantly,” he added.

“Yeah, but if it wasn’t hard, it’d be boring,” I said, and he seemed to like that.

Now he’s gone and it’s just me and Dom. It’s a little awkward, to tell you the truth. My leg is throbbing inside the cast, but instead of convincing the doctors to give me more painkillers, like I told him to, Dom keeps bustling around getting things: balloons from the gift shop, way too much candy from the cafeteria. I know he’s feeling guilty, or whatever, because his eyes are all red like he’s been crying, but I’d rather he just sit still and apologize instead of feeling sorry for himself. Not to be a jerk, or anything.

“Quit spending all Mom’s insurance money on crapola,” I snap, when he comes in with an armful of miniature teddy bears. “Just sit with me, for instance.”

“Okay,” he says, too cheerfully. He positions each of the bears carefully on my windowsill, then lowers himself into the chair beside my bed. “Lots of people are calling the hospital about you, Pickle. The doctor can’t tell them anything, obviously, but I made a list of names in case you wanna call somebody back.” He digs in his back pocket, pulling out a crumpled sheet of paper.

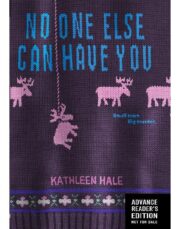

"No One Else Can Have You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No One Else Can Have You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No One Else Can Have You" друзьям в соцсетях.