Some of the girls were deliciously scandalized at the chance to talk to an imprisoned English milord. Nicolette was a kind girl with some interest in Grey as an individual. Occasionally she dropped an apple or other fruit between the bars. He devoured her offerings, amazed that he’d ever taken apples for granted.

Nicolette told him of her sweetheart and bid him a fond farewell when she left the castle to marry. He gave her his blessing, for he had nothing else to give.

None of the other maids visited as much, but he still had occasional visitors. For a time there was a boisterous young ostler from the stables who taught Grey highly obscene French drinking songs until the man was fired for drunkenness.

Grey treasured those moments of normality. They helped keep him sane.

Chapter 7

France, 1813

Madame Leroux was right, and Cassie did a brisk business at the small market in the village square. She rather enjoyed being a peddler. Since she didn’t depend on selling to support herself, she could be flexible on prices. It was a pleasure to be able to sell a pretty ribbon to a girl who had never owned anything pretty.

The thieves’ oil was popular, too. With winter illnesses rampant, buyers would try anything that might help. Customers were also interested in news, as isolated villagers always were. Yes, the news from Russia was bad, but the emperor had escaped safely, and wouldn’t this length of lace look lovely on your daughter’s wedding dress?

By noon there were no more customers, so it was time for the castle. Cassie ate a bowl of thick bean soup at La Liberté, thanked Madame Leroux for her help, and left St. Just du Sarthe. Instead of heading for the next village, she drove up to the castle. The narrow road was bleak and windy, and the castle was equally bleak when she reached it.

The castle proper was surrounded by a looming wall that had never been mined for stone. The massive gates stood open so people and vehicles could come and go easily, but the gates looked as if they could still be closed in an emergency.

She drove through the gates unchallenged. The walls cut the bitter wind once she was inside. Not seeing anyone, she drove around to the back of the castle and left pony and cart within the shelter of the mostly empty stables. Then she slung her peddler’s bag over one shoulder and went hunting for the entrance to the servants’ area.

After two locked doors, she found one that opened under her hand into a short passage leading into the castle kitchen. The long room was warm and there were pleasant smells, but there was no one in sight. Cassie called, “Hallooo! Is anyone here?”

A hoarse woman’s voice replied, “What do you want?”

A heavy-set woman pulled herself from a wooden chair by the fire and limped toward Cassie. Her round face looked designed for smiles, but she was wrapped in shawls and coughed every few steps.

“I’m Madame Renard, a peddler, and I see that you’re a candidate for some of my throat lozenges. Here, a sample.” Cassie fished a packet of honey and lemon lozenges from her bag. They tasted good and did help soothe a cough.

“Don’t mind if I do.” The woman removed a lozenge from the packet, then sank onto a bench. “Merci. I’m the cook, Madame Bertin.”

“I was told most of the people here at the castle were ill.” Cassie glanced around the kitchen. A pot hung on the hob by a fire that had burned down to embers. “You look like you could use some help. Shall I build up the fire for you?”

“I’d be most grateful,” the cook said. “There’s chicken broth in the pot there. Could you get me some?” She coughed wrenchingly. “Everyone is sick in bed, can’t even manage stairs. I’ve got hot food for anyone who wants it, but no one has made it this far and ’tisn’t my job to wait on other servants.” More coughing.

“I hope no one is dangerously ill?” A ladle hung by the fire, so Cassie scooped warm broth into a porringer on a nearby table.

“The housekeeper died early on, but she was old and sickly already. I don’t think anyone else is in mortal peril, but this winter’s influenza makes a body weak as a kitten for days.” Madame Bertin sipped the hot broth appreciatively. “I kept the fire from dying and managed to make this broth, but now I’m too tired for anything else.”

Seeing an opportunity, Cassie asked, “Would you be willing to pay a bit for some help, madame? I could carry trays of bread and broth to the servants who are ill, and perhaps do some chores around the kitchen.”

“’Twould be a real blessing. Let’s see, who lives in …” The cook thought. “There are six maids in the attics and two men in the stables. The stairs are just through that door, but it’s five long flights of steps to the attic. Can you manage that much?”

“I’m spryer than I look. I’ll be happy to help out. When people are ill, they need something warm.” She stirred the broth with the ladle. “And I’ll be glad to earn a few coins, too. Where do you keep the bread? Cheese would also be good. Strengthening.”

“The pantry is there.” Madame Bertin pointed. “A good thing Citoyen Durand isn’t here. He’d be raging and whipping people to do their jobs even if they’re too ill to stand. But what is going to happen in a quiet place like this in the dead of winter? We can all rest a day or two until we’re ready to work again.”

“Fortunate,” Cassie agreed. She filled mugs, cut bread and cheese, and carried a tray out to the stables, where she was gratefully received. After returning to the kitchen, she prepared more trays for the maids. With six of them, she needed to make two trips up the narrow stone stairs. No wonder Madame Bertin hadn’t even tried.

As the cook said, no one seemed at death’s door, but all the servants lay limp in their beds, weak, tired, and very glad for sustenance. Cassie made a silent prayer that the thieves’ oil would protect her. Becoming that ill while traveling would be very bad.

She returned to the kitchen, where the cook was drowsing in her chair by the fire. Cassie tucked a knee robe around her. The time had come to learn if there really was a dungeon with prisoners. “Is there anyone else I should take food to?”

Madame Bertin frowned. “There are the guards and the prisoners in the dungeon. The head jailer, Gaspard, usually sends a man up for food, but one is ill, Gaspard is off somewhere, and the one there now wouldn’t dare leave his post.”

“So the guard and the prisoners need feeding? How many prisoners are there?”

“Only two. With everyone ill, they’re being neglected.” The cook crossed herself. “One of the prisoners is a priest. ’Tis very wrong to lock up a priest, but Durand would be enraged at the impertinence if anyone told him so.”

“Shocking!” Cassie agreed. “What is the other prisoner?”

“They say he’s an English lord, though I’ve never seen him, so I can’t say for sure.” She shook her head sadly. “No doubt an Englishman deserves a dungeon, but surely not the priest. He is old and frail and needs hot food in this weather.”

“I’ll take food down to all of them.” Cassie started to assemble a tray. “You say you’ve never seen the prisoners. They are never brought up for exercise in the yard?”

“Oh, no. Citoyen Durand is very strict about his prisoners. They are never released from their cells, and the guards never enter. Food is put through a slot.” Madame Bertin crossed herself again. “The poor devils must be half mad by now.”

Cassie’s lips tightened as she prepared the food. After ten years of uncertainty, Kirkland’s search might be about to end. But his long-lost friend might be broken beyond any chance of mending.

Chapter 8

Castle Durand, 1805

Grey regarded the sparrow that perched on his sill. “Enter, Monsieur L’Oiseau. I’ve kept a bit of bread for you. I hope you appreciate what a sacrifice this is.” The bird cocked its head, undecided, so Grey whistled his best imitation of sparrow song. Reassured, it glided from the sill to the floor and pecked at the bit of bread Grey had saved.

He enjoyed talking to the birds. They never contradicted, and he was amused by their saucy willingness to approach. “Cupboard love,” he murmured, tossing another crumb. “Not so very different from being an eligible prize in the marriage mart.”

He’d been old enough to experience some of that in London before his disastrous decision to visit Paris. Kirkland and Ashton, who paid more attention to politics, had both warned him to keep his trip short since peace wouldn’t last, but he’d characteristically brushed them off. He was the golden boy, heir to Costain, to whom nothing evil could happen.

Two years later, here he was, slowly going mad with boredom and grateful for the fleeting companionship of a sparrow. But at least he was stronger and more fit than before, and his singing voice had improved.

He tossed another crumb. The sparrow seized it, then cocked its head for a moment before flying up and out the window. Grey watched the bird leave with an envy so deep that it was pain. Oh, to be able to fly free! He’d wing his way over the channel and home to the beautiful hills and fields of Summerhill.

Since his company had left, he rose and began running in place, calling up images of his childhood home. Those had been happy days at Summerhill, which was blessed with a mild south coast climate. Fertile fields and plump, happy livestock. He’d loved riding the estate with his father, learning the ways of a farmer without even thinking about it. His father had been a good teacher, challenging his heir’s mind and curiosity.

The earl had also talked government and the House of Lords and what would someday be expected of Grey when he became the Earl of Costain. But that had been unimaginably far in the future. His parents were young and vigorous, and Grey would have many years to sow wild oats before it would be time to settle down.

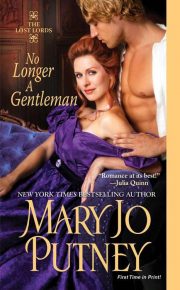

"No Longer a Gentleman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No Longer a Gentleman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No Longer a Gentleman" друзьям в соцсетях.