She settled in the chair beside him with her own food and wine. She tasted cheese on bread, pâté on bread, then both plus relish. As he said, ambrosia. “How did you keep your strength up under such dreadful conditions?”

“I exercised. Ran in place, lifted the two stones that served as furniture, kept moving as much as I could.” He shrugged. “At the beginning, there was barely enough food to keep a rat alive, but the rations improved after Père Laurent was imprisoned.”

“The castle cook thought it outrageous that a priest was so ill used, so she sent larger servings down for you both,” Cassie explained.

“I owe the cook thanks. There was never enough food to feel really full, but it was sufficient to keep me from weakening.” He spread pickle relish on a piece of bread and cheese. “There was nothing better to do, so exercise at least filled some time.”

“Exercise and singing?”

He smiled a little. “That and remembering poetry and the like. I was not an ideal student. It never occurred to me that an education might help me cling to my sanity.”

“A well-furnished mind must be a great asset when one is imprisoned.”

“Père Laurent’s mind is extremely well furnished. I encouraged him to tell me everything he knew.” Grey spread pâté lavishly. “Cassie, what happens next?”

“We need to stay here a day or two until the roads clear,” she said. “Then north to the English Channel, where smugglers can take us home.”

“Home,” he repeated. “I don’t know what that means anymore. I was a typical young man about town, drinking and gaming and chasing opera dancers. A useless life. I can’t go back to that. But I don’t know what I can go back to.”

“Ten years have passed,” she said slowly. “You would have been a different man now even if you’d been safe in England the whole time. You might have married and become a father. You might have entered politics since you’ll be in the House of Lords in time. Many paths are open to you, and you can take your time in choosing.”

“Even thinking about a night at the opera, or a boxing mill, or a gaming club frightens me,” he said bleakly. “So many people! I don’t know if I can bear that. That was one reason I went out to the pond. Even half a dozen kind people were too many.”

“After ten years of solitary confinement, it’s not surprising if you find the thought of crowds appalling,” she agreed. “But you can avoid them until and unless you’re ready. You’re a nobleman. You can be a splendidly eccentric hermit if you like. Since you were outgoing and enjoyed people before, it’s likely you will again. In time.”

“I hope you’re right.” He glanced across at Cassie, his gaze hooded. “Do you have the apple brandy?”

“Since you’re unused to strong spirits, it might be wiser not to indulge in more,” she observed. “Unless you want to greet your first day of freedom with a pounding head.”

He let his head rest on the chair back. “I expect you’re right. Even though I didn’t drink that much by the pond, I seem to be babbling away quite frivolously.”

“It’s not surprising you want to talk about what lies ahead, and I’m the best choice because I know England,” she pointed out. “And I am safe. After we reach England, you’ll never see me again, and I am not of a gossipy disposition.”

“What you are is a mystery, Madame Cassie the Fox,” he said softly. “What is your story?”

Chapter 14

As soon as Grey spoke, Cassie drew into herself, strength and intelligence vanishing behind the façade of a tired old woman. He wondered how old she really was. He’d first guessed her at twice his age, around sixty, but she did not move like a woman of so many years. When she wasn’t trying to look feeble and harmless, she had the litheness of a fit younger woman despite her gray hair and lined face.

Wanting to hear her lovely, smoky voice, he continued, “Why are you here, looking and talking like a Frenchwoman while serving an English master?”

“I serve no master, English or otherwise,” she said coolly. “Since I wish to see Napoleon dead and his empire smashed, I work for Kirkland. He shares my goals.”

Grey thought about how much he didn’t know. “The war. Is Napoleon winning? Durand would taunt me with news of French victories. Austerlitz. Jena.” He searched his memory. “He mentioned many other victorious battles as well.”

“Durand told you only one side of the story,” she said, amused. “There have been great French victories, but not lately. The French fleet was destroyed at Trafalgar in 1805, and Britain has ruled the seas ever since. In the Iberian Peninsula, the British and local allies are driving the imperial army back into France.”

“What about Eastern Europe? The Prussians, Austrians, and Russians?”

“The emperor has defeated the Prussians and Austrians several times, yet they will not stay defeated,” Cassie said. “In an act of staggering stupidity, last summer he invaded Russia and lost half a million men to General Winter. The sands of Napoleon’s hourglass are running out.”

Grey exhaled with relief. “All of these years, I’ve wondered if England was about to be conquered.”

“Napoleon is a brilliant general,” she admitted, “but even he cannot defeat all of Europe. If he had been content to stay within France’s borders, he could have had his crown, but his lust for conquest is his undoing.”

What else did he want to know? “You mentioned my classmates at the Westerfield Academy. What of them? And Lady Agnes?”

“Lady Agnes is well and continues to educate her boys of good birth and bad behavior.” Cassie smiled. “I met her only once, but she’s not a woman one forgets.”

He felt a rush of relief. Lady Agnes was far from ancient, but ten years was a long time. She had been as important in his life as his own mother, and he was glad to know she was well. “What of the others? Kirkland is obviously alive and apparently active in the spying trade.”

Cassie nodded. “He divides his time between Edinburgh and London as he runs his shipping company. Intelligence gathering is a secret sideline.”

He thought of the friends who had become closer than brothers in his years at school. “Do you know how any of the others are doing?”

Her brows furrowed. “I’m not well acquainted with most of them. The Duke of Ashton is well, recently married, and expecting his first child. Randall was a major in the army, but he left after becoming heir to his uncle, the Earl of Daventry.”

Grey had a swift memory of Randall’s taut expression after receiving a letter from his uncle. “He hated Daventry.”

“And vice versa, I’ve heard, but he and Daventry are stuck with each other and have apparently declared a truce,” Cassie said. “Randall is also recently married. He seemed very happy the time I met him. His wife is a lovely, warm person.”

“I thought he’d be a confirmed bachelor, but I’m glad to hear otherwise.” If ever a man needed a lovely, warm wife, it was Randall. Thinking of his other classmates, he asked, “What of Masterson and Ballard?”

“Masterson is an army major, and Ballard is working to rebuild the family wine business in Portugal.” Her brow furrowed. “You must have known Mackenzie, Masterson’s illegitimate half brother. He has a very fashionable gaming club in London. Rob Carmichael is a Bow Street Runner.”

Grey’s brows arched. “Rob would be good at that, but it must have driven his father into a frenzy.”

“I believe that was part of the reason he became a Runner,” she said with amusement. “Those are the only Westerfield students I know, but when you’re back in London your friends will be happy to bring you up to date.”

The thought of London created a knot of panic in Grey’s gut. His friends’ marriages also made him sharply aware of how much time had passed. They had grown up and taken on adult responsibilities. Grey had merely … survived.

Uncannily perceptive, Cassie said softly, “Don’t compare your life to theirs. You can’t change the past, but you are returning to family, friends, and wealth. You can have the future you dreamed of in captivity.”

He wanted to blurt out that he was no longer capable of having the life he was born to. His confidence, his sense of himself and his place in the world, had been shattered. As a future earl, he would have no trouble acquiring a wife eager to spend his money, but where would he find a wife who was willing and able to deal with the darkness of his soul?

But whining was ugly, especially to a woman as fearless as this one. He was still amazed at how she’d come to see if he might be in Castle Durand, seen an opportunity to free him, taken down a guard, and led him and Père Laurent to safety through a blizzard. Maybe that strength was why he found her so attractive.

Madame Boyer was an attractive woman in her prime. Her daughter Yvette was a lovely girl with a face to inspire young, bad poets. Yet it was drab, aged Cassie the Fox who intrigued him. Though she might be his mother’s age, she had a lovely, delicate profile, a smokily delicious voice, and a core of tempered steel.

Wanting to know more of her, he stated, “Tell me about your family.”

She leaned forward to put another piece of wood on the fire. “My father was English, but we made long visits to my mother’s family in France. We were here when the revolution broke out.” She settled back in her chair, her face like granite. “I said we must return to England immediately, but my warnings were dismissed by the rest of the family.”

“Cassandra,” he said, remembering his Greek studies. “The Trojan princess who saw the future, but couldn’t convince anyone of the danger she foretold. Did you choose that name for that reason?”

She winced. “No one else has ever made that connection.”

“Cassandra was a tragic figure,” he said softly, wondering how closely her story resembled the myth. “Did you lose your family as she did?”

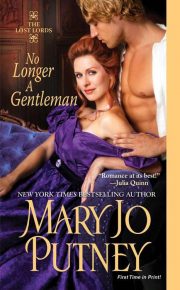

"No Longer a Gentleman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No Longer a Gentleman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No Longer a Gentleman" друзьям в соцсетях.