You’re being stupid and predictable, she told herself. The combination of that damn potato chip and Jacob in those paint-splattered jeans (which looked as good on him as jeans could look on a man) and Valerie cheating on her husband, John, and Antoinette, who was cheating on no one because she belonged to no one, but who hinted she’d been having crazy sex herself lately, led Kayla down this path of suspicion. There had been times in the last five years when she’d watched Raoul sleep, when she’d reached over and touched his penis, hot and erect, and she’d wondered, Is he dreaming about me? How could she ever be sure? Raoul always assured Kayla that he thought she was beautiful, but she had gained weight after four children, and she waged a constant war with herself to stay in shape. She looked okay for forty-two, but not great-certainly there were women on the island who were ten times as attractive, thanks to gyms and plastic surgery and plain, old-fashioned good genes. Kayla closed her eyes for a split second. Maybe she was too sensitive; maybe she did need one of Val’s goofy books-You’re Okay But I’m Better, Ten Steps to Your Own Uniqueness; Stop Biting Your Nails, Start Building Your Future. When Kayla opened her eyes she relaxed, because she saw Raoul’s red truck coming down Monomoy Road toward her.

They stopped in the middle of the road, Kayla in the Trooper, Raoul in his big red truck, and he turned down the radio and smiled and said, “Hi, baby.”

Kayla unfastened her seat belt and slid her body out her open window far enough to kiss him. He tasted like himself.

“Where’d you go?” she asked.

“Town Building. I had to check on some easements. I bumped into Valerie, and she reminded me about your séance tonight.”

Kayla slithered back into her car. “It’s not a séance, Raoul.”

He checked his side mirror, but no one was coming. Even in summer, two people could sit in the middle of the road and have a conversation without interruption. “I’d just love to know what you ladies do out there in the middle of the night.”

“I’m sure you would,” Kayla said. “But it’s none of your business.”

“I know, I know. It’s a woman thing. Estrogen required for inclusion,” Raoul said. “Now tell me, how did Theo seem this morning?”

“The same. I asked him if he was excited about school next week, and he didn’t answer. I asked him to pick Luke up from camp at four o’clock, and he sort of grunted.”

Raoul tapped his head against the headrest. “Tell you what. This weekend I won’t work Sunday or Monday. I’ll take Theo fishing and have a heart-to-heart with him.”

“Let’s hope that works,” she said.

“What time are you leaving tonight?” Raoul asked.

“Eleven-fifteen,” she said. “I’ll be back in the morning before you go to work.”

“Good,” he said. He kissed his fingers by way of good-bye and drove off.

It was half past three, which gave Kayla enough time to dash into the Stop & Shop for two pints of raspberries; then it was down to Fahey & Fromagerie on Pleasant Street, where she bought a hunk of pale, creamy Saint Andre cheese and two slender baguettes dusted with flour. There was a selection of olives and red peppers, marinated mushrooms and salami-the kind of special, wonderful things her kids wouldn’t eat. They also had chicken salad without too many unidentifiable chunks, and a cucumber-dill-sour cream thing and she got two pounds of each for dinner. By the time Kayla left the cheese shop, it was two minutes to four, and she had to head over to the school to spy on her sons.

Kayla wished she didn’t have to do this, but Theo’s odd behavior of the last month or so left her no choice. She meandered through the back streets so that she cruised by the school at ten past four, and sure enough, there was Luke in his green Nantucket Day Camp T-shirt, holding two cupcakes on a paper plate and a purple balloon, squinting against the sun. Her fifty-year-old son trapped in an eight-year-old body. Luke had been an old man since he was born. He liked order, he liked adhering to rules, he liked promptness. Kayla had him on a schedule when he was only three weeks old, and later, he refused to eat unless he was wearing a bib. Kayla had read somewhere that the youngest child in the family was the most likely to be footloose and fancy-free, but not this one. Kayla and Raoul had dubbed Luke the child most likely to develop an ulcer. The inefficiency of the world around him was always letting him down.

Kayla pulled up next to the curb, and Luke opened the door. The plate of cupcakes covered neatly with plastic wrap went on the seat between them, and then he tucked the balloon into the car.

“Theo never showed,” he said, and in his voice was the unmistakable tone: Kids today. You just can’t trust them.

“It’s only ten after,” Kayla said, pulling into a vacant parking spot. “Let’s give him the benefit of the doubt. We’ll wait here five minutes and see if he shows up.”

Luke sighed deeply and fastened his seat belt. There was a faint pink juice stain above his upper lip. He tapped one of his little black soccer shoes against the floor mat,

“So how was the last day of camp? You had a party, I take it.”

Luke nodded, crossed his arms over the front of his T-shirt.

“I’ll bet you’re glad you don’t have to wear that shirt anymore,” Kayla said. “We can use it for a rag.”

Luke plucked the shirt away from his body and sniffed it. “Be sure to wash it first,” he said.

They watched the cars pass on Surfside Road. People were leaving the beach, the tops of their Jeeps down, damp towels wrapped around the roll-bars. Contractors who kept normal hours headed home in their pickups. A few cars honked their horns joyfully; it was, after all, the start of a holiday weekend. The last weekend of summer.

“Mom,” Luke said, staring resolutely out the window. “Theo isn’t coming.”

Kayla turned the key in the ignition. “Okay,” she said. “Let’s go.”

Predictably, at home, Theo’s Jeep was in the driveway. Luke refrained from saying anything, and Kayla followed suit. They headed inside. Theo sat at the breakfast bar in just his swim trunks, inspecting his toenails. He did not look up when they came in.

“Hello,” Kayla said. She put the groceries in the fridge. Theo stood up and intercepted the cucumber salad; he got a fork and started eating right from the plastic container. Luke glared at him as if to say: Barbarian. Luke wrote his name in block letters on a piece of masking tape and put the tape over the plastic covering his cupcakes.

“These are mine,” Luke said.

“Fuck off,” Theo said.

Luke looked at Kayla as if to say: Are you going to tolerate this?

“Theo,” Kayla said, as nonconfrontationally as possible, “that salad is for all of us.”

“You’re contaminating it,” Luke said. “With your fork.”

Theo stopped, stared at his little brother. “I said, fuck off.”

Kayla ushered Luke out of the kitchen, and he whispered to her, “You forgot to yell at him for not coming to get me.”

“I didn’t forget,” she said. “I’m just picking my moment.”

“I’m telling Dad,” Luke said.

“Me, too,” she said, and this seemed to satisfy him.

The girls were in the living room. Jennifer was watching Oprah, and Cassidy B. was reading the latest Harry Potter book, finishing the bag of Lay’s potato chips.

“I can’t believe you’re eating those,” Jennifer said to her. “You might as well be ingesting poison.”

Cassidy B. shrugged.

“Hi, girls,” Kayla said.

“Theo forgot to pick me up,” Luke announced.

“So?” Jennifer said.

Cassidy B. didn’t look up from her book. Kayla’s girls were like before and after pictures of adolescence. At fourteen, Jennifer was showing all the signs of womanhood: She had breasts, and long, shiny dark hair, her voice was throaty. She worried about her weight and her complexion; she read the nutrition information labels of everything she ate. Cassidy B. was eleven and still a child. She had baby fat and a clear, untroubled look in her eyes. When she had friends over, they read or played with Cassidy’s dollhouse.

Kayla loved her children so much that she kissed the three of them. First she kissed Luke’s juice-stained lips; then she kissed the side of Cassidy B.’s face while she read, and even Jennifer let Kayla kiss her, a quick, dry kiss on top of her sweet-smelling hair.

Theo came into the living room, still eating the cucumber-dill salad. “What the fuck is going on in here?” he said.

Now Kayla had three kids looking at her as if to say: Are you going to tolerate this?

And then the phone rang.

“Kayla?”

It was Antoinette. The woman had the sexiest voice on the planet. It was dark and exotic, like sandalwood, like expensive chocolate.

“Hi.”

“What’s going on?”

“You’re supposed to bring the lobster tails,” Kayla said. She checked the kitchen clock; it was half past four. “Can you swing it? If not, I’ll send Theo to East Coast Fish. He owes me.” Kayla turned around, and there was Theo, staring at her. He was such a handsome kid-brown hair bleached a shade lighter by the sun, golden brown eyes, and an incredible tan-he was his father all over again. Yet the way he looked at her was disturbing. Always, now, these disturbing looks, like he knew something about her that she didn’t know herself.

“I can swing it,” Antoinette said. “I have time.”

“Of course you do,” Kayla said. Antoinette was the freest person Kayla knew, and as if to illustrate the concept, Luke stepped through the sliding glass doors onto the deck, holding his purple balloon, and he let it go. It floated away.

Kayla put her hand over the receiver. “Luke, honey, why did you do that?”

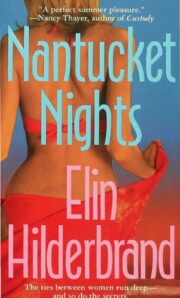

"Nantucket Nights" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nantucket Nights". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nantucket Nights" друзьям в соцсетях.