Luke came back inside, glared at Theo, and marched off, stomping his soccer shoes.

“Do you want to borrow a couple of kids?” Kayla asked Antoinette.

“Looks like I might be seeing my own this weekend,” Antoinette said.

“Your own what?”

“My own kid.”

Kayla was silent. Back in the reaches of Antoinette’s past was a daughter whom she’d given up for adoption and never seen again.

“You mean…”

“She called a few days ago. Her name is Lindsey. Lindsey. A white name if ever I heard one.”

“Is… is she white?” Theo was still glaring at Kayla, and she covered the receiver again with her hand. “Do you mind?” she asked.

“No,” he said coldly, his eyes not leaving her face. “I don’t mind.”

Kayla stepped out onto the deck and scanned the horizon for Luke’s balloon, but it was gone already.

“She wasn’t white when I knew her,” Antoinette said. “She wasn’t black or white. She was… well, I remember thinking she was the color of a wine cork. Obviously I’m a woman who drinks too much. This whole thing has hit me sideways. This whole thing is fucking me up.”

“Yeah, I believe it,” Kayla said. “So she’s coming this weekend?”

“Tomorrow. I tried to explain to her that I live in the woods on an island thirty miles out to sea. I tried to explain to her that I wasn’t much of a people person. Didn’t seem to faze her.”

Kayla felt vaguely uncomfortable, and when she turned around, there was Theo standing in the sliding glass door, staring at her.

“Let’s talk about it tonight, okay?” Kayla said. “I have to go.”

“Lobster tails?” Antoinette said.

“Yeah.”

“You’ll pick me up at quarter to twelve?”

“Not a minute later.”

Kayla clicked off the phone, and Theo immediately lost interest in her. He put the top back on the cucumber salad, delivered it safely to the fridge, and deposited his fork in the dishwasher. Model child. He disappeared while Kayla stood there thinking about Antoinette’s long-lost daughter showing up, tracking Antoinette down like something off Geraldo or Oprah. Tracking down a birth parent-it was cliché by now, wasn’t it? And yet Kayla, at least, was interested. What had it felt like to give up a child? And what would a child of Antoinette’s look like? Antoinette never told Kayla if her husband was black or white, and Kayla had been too afraid to ask. The color of a wine cork? What did that mean? More white than black? More black than white?

Before she determined why this question intrigued her or if it even mattered, Theo was back-he’d put on a T-shirt and a pair of flip-flops, and he was rattling his car keys.

“You’re going out?” she said.

He, naturally, did not respond. Pointless to ask where he was going or if he’d be back for dinner. He climbed into his Jeep and drove away. Kayla stood in the door and watched him go.

“Do you think they’ll all act this way?” Kayla asked Raoul later that night. She told Raoul about Theo forgetting Luke, about the foul language, the staring, the aggressive silence. It was more of the same.

Raoul leaned back in the dining chair and it creaked. It was almost ten o’clock. Luke and Cassidy B. were in bed, Jennifer was sleeping at a friend’s house, Theo hadn’t returned. Kayla and Raoul finished up the cold salads by candlelight.

“I don’t know, Kayla.”

“Do you think we should take away the car?”

“Then you’d have to shuttle him around,” Raoul said. “No. Grounding him is grounding ourselves.”

Kayla sighed. “You’re going to have to talk to him,” she said. “Maybe all he needs is one-on-one with you. Maybe the fishing will do it.”

“Maybe,” Raoul said. He rubbed his eyes. “This will pass, Kayla.”

Easy for you to say, she thought. You’re never home. And so, all of Theo’s defiance seemed aimed at her. The summer had started out fine. Theo worked at the airport, and he drove around in his Jeep. Did Kayla need errands done? Theo was there to help-to run to the Stop & Shop, Bartlett’s farm, East Coast Fish. Nights, he squired his friends and an endless stream of girls to parties and bonfires at the beach. Theo was already close to being the most popular kid at Nantucket High School, and when he got the car, the phone never stopped ringing. Kayla could have easily filled her day being Theo Montero’s personal secretary.

And then, at the end of July, something happened. Theo turned, like sour milk. He stopped answering phone calls from his friends; he vanished for long periods of time without explanation. He swore. He locked himself in his bedroom and masturbated- Kayla heard him more than once, the heavy breathing, the moaning-and she sneaked away from his room hot-faced, embarrassed. It was natural, she knew, but it was as if he wanted her to hear him being openly and defiantly sexual in the house.

Kayla scanned her mind over the last few weeks. Nothing unusual jumped out. By that time, the summer had a rhythm: the sun, the garden, burgers on the grill, baby-sitting, camp, the phone ringing. One night while Theo was out, she and Raoul searched his room. Kayla felt evil and intrusive, doing this thing she swore she’d never do-opening his drawers, checking between his mattress and box spring. They were looking for Baggies of weed or warm beers, but they didn’t find so much as a Playboy. Theo’s room was messy with baseball mitts and boxer shorts and a copy of The Scarlet Letter. Raoul picked up the book.

“Somehow I don’t think Hawthorne is behind all this,” he said.

It was a phase, Kayla kept telling herself. Theo was eighteen, a year older than the rest of his classmates because he’d contracted mono in the third grade and they’d decided to hold him back. Theo was suffering from growing pains, maybe. Many of his friends were a year ahead of him, and they were graduating, leaving the island for Amherst, Burlington, Charlottesville.

Back when the behavior started, Kayla stumbled upon Theo in the kitchen in the middle of the night. He was standing before the open refrigerator drinking milk from the plastic container. She watched him a minute before she spoke, the light from the fridge cast a bluish glow on his half-naked body-her beautiful, angry son.

“Theo,” she said. “Is something bothering you?”

He paused his guzzling. “Yeah,” he said. “You.”

“Did you have a fight with your friends? Did something happen at work?”

Theo didn’t answer.

“Theo,” she said, “just tell me what you’re thinking.”

Theo put the milk back into the fridge and returned to his room, slamming the door.

Two weeks ago at her yearly checkup, Kayla told Dr. Donahue that Theo’s behavior was keeping her up at night. Dr. Donahue was sixty-nine years old, working through retirement, and he was infamous for healing what ailed you, or what didn’t ail you. He prescribed Ativan, a sedative, for her nerves. “How old is that boy?” he asked. “Eighteen? He’ll be out of the house before you know it.”

In another hour, Raoul was fast asleep and Kayla got ready for Night Swimmers. She changed into sweatpants, a red MONTERO CONSTRUCTION T-shirt, tennis shoes. When she stepped out onto the deck, the yard was bathed with moonlight. The first full moon in the history of Night Swimmers. Maybe it was a sign.

Here was how Night Swimmers began:

When Kayla was twenty-two years old and new to Nantucket and didn’t know a soul, she rented a room in a cottage on Hooper Farm Road for the summer. The cottage was small and poorly constructed, but she had just finished living in a dorm at UMass, so to her, the cottage was a castle. Also renting rooms in that cottage were Valerie Mclntyre and Antoinette Riley. Like Kayla, Valerie was just out of college, and headed to law school at NYU. Val wanted to take law school by storm-impress the professors, date the smartest guy in her section, and land a job with Skadden, Arps in New York City. She wanted Law Review and a year clerking for Judge Sechrist on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. All this so she could one day get married, have children, and open her own practice on Nantucket. Kayla admired Valerie’s ambition; she admired her plans. Kayla had no plans other than to buy a bicycle and find a job and maybe a boyfriend and go where the summer took her.

Antoinette was three years older than Kayla and Val; she was dark-skinned like an Egyptian priestess. That was one of two things Antoinette told them about herself on the day she moved in. “Three quarters African American, one quarter French Huguenot. My maternal grandmother was the Huguenot. Now you know, so you can quit gawking.”

Kayla never imagined having a black roommate. But she was thrilled. Valerie, who was into her self-help books even then, said to Kayla, “There is one big difference between us and Antoinette, and it has nothing to do with skin color. You and I are fusers. We like other people. But Antoinette, she’s an isolator. She prefers to be by herself.”

It seemed true: Kayla and Valerie were fast friends. They each got jobs in town. Kayla worked at Murray’s Toggery peddling Lilly Pulitzer skirts and Top-Siders, and Valerie sold tiny gold lightship baskets at a jewelry store. They spent their free days on Nobadeer Beach, and their free nights doing the bump at the Chicken Box. Kayla reveled in the new friendship, but she felt uncomfortable excluding Antoinette. It did feel like a racial issue-the two white girls leaving the black girl at home. And so, Kayla invited Antoinette everywhere-to the movies, to the bars, to the beach. Antoinette always declined in the same taut, definitive way. “No.” And then, as an afterthought, “Thanks.”

Antoinette didn’t have a job that summer; she was spending her time “recovering.” That was the other thing she told them when she first moved in: She had come to Nantucket to recover. Recover from what? It was an endless source of speculation between Kayla and Valerie. Antoinette wasn’t a recovering alcoholic-she purchased cold chablis at the liquor store, poured it into one of the Waterford goblets she had brought to Nantucket, and drank alone in her room. She wasn’t a recovering drug addict- when Kayla and Valerie lit up a joint before they went out to the Chicken Box, Antoinette would poke her head out of her bedroom and ask if she could have a toke. They pushed the dope on her eagerly, hoping it would make her talk, but it shut her up even more. After smoking, Antoinette’s eyelids drooped, her mouth clamped shut, and she retreated back to her room, arms crossed over her chest.

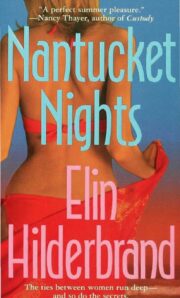

"Nantucket Nights" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nantucket Nights". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nantucket Nights" друзьям в соцсетях.