Mary laughed. "That is no way to ingratiate yourself with a lady, Mr Maddox! You should be thankful that your profession does not require you to obtain information under cover of flirtatious gallantry.You would never resolve a crime again."

She had meant it as a joke, but his face fell, and she felt, for a moment, as remorseful if she had chosen her words on purpose to wound him.

"I am sorry, Mr Maddox, I did not mean — "

He waved his hand. "No, no. Think nothing of it. I was merely momentarily discomfited. The conversation is not going in the direction I had intended."

"And what did you intend, Mr Maddox?"

"To ask you to marry me."

She could not pretend it came as a surprise; she had been aware, for some time, of a particularity in his manners towards her, and since her convalescence, his attentions had become so conspicuous that even Dr Grant could not avoid perceiving in a grand and careless way that Mr Maddox was somewhat distinguishing his wife’s sister. But all the same, as every young lady knows, the supposition of admiration is quite a different thing from a decided offer, and she was, for a moment, unable to think or speak very clearly.

"I see I have taken you by surprise," he said. "You will naturally wish for time to collect your thoughts. Allow me, in the mean time, to plead my case. It is, perhaps, not the most romantic language to use, but you are an intelligent woman, and I wish to appeal, principally, to that intelligence. I know you have an attachment to Mr Norris — " she coloured and started at this, but he continued, "I have no illusions, Miss Crawford. My affections are, I assure you, quite fervent enough to satisfy the vanity of a young woman of a far more trivial cast of mind than your own, but I have known for some time that I would have a pre-engaged heart to assail. I know, likewise, that you will now be a woman of no inconsiderable fortune. But what can Mr Norris do for you — what can even your brother do — compared to what I shall do? I am not the master of Lessingby, but I am, nonetheless, a man of no inconsiderable property. If such things are important to you, you may have what house you choose, and have it completely new furnished from cellar to attic, and dictate your own terms as to pin-money, jewels, carriages, and the rest. But I suspect such things are not important to you. My offer to you is independence. Heroism, danger, activity, adventure. The chance to travel — to see the world. All the things that men take for granted, and most women do not even have the imagination to dream of, far less embrace. But you, I fancy, are an exception. What would be tranquillity and comfort to little Maria Bertram, would be tediousness and vexation to you. You are not born to sit still and do nothing. Even if he makes a complete recovery, which is by no means certain, you are no more fitted to be Edmund Norris’s sweet little wife than I would be. And if he does not recover, you will waste your youth and beauty pushing an invalid in a bath chair, buried in a suffocating domesticity. Do not make the mistake of marrying a man whose understanding is inferior to your own — do not hide your light under a bushel, purely to do him credit. You are worth more than that — you can achieve more than that. I know enough of you already to be quite sure that you would be an inestimable support to me in my profession — and not merely a support, but a partner, in the truest, fullest sense of the word. Your eye for detail, your capacity for logical thinking and lucid deduction, surpass anything I have seen, even among men whom I admire. You have a genius for the business, Mary, and if you do not choose it, it seems that it chooses you."

She drew back in confusion, aware that she ought to be displeased at the freedom of his address, but he had already taken her hand — not with lover-like impetuosity, but with cool deliberation; he lifted her fingers slowly to his lips, his eyes on hers in a gaze of passionate intensity. Something passed between them, that Mary felt all over her, in all her pulses, and all her nerves. Denial was impossible; there was a connection between this man and herself; an attraction that she had long been blind to, and even longer denied.

Such reflections were sufficient to bring a colour to her pale cheeks; a colour that Maddox saw, and seized upon. But he knew better than to press her.

"I am very sensible of the honour you are paying me, Mr Maddox," she began, dropping her eyes.

"But?"

"But I will need some time to consider it."

"Of course," he said, getting to his feet, and preparing to go. "Pray take all the time you need. My own affections are fixed, and will not change. I love you, Mary Crawford, and I give you my word, that in marrying me, you will lose nothing you value that is associated with that name, and you will gain a freedom that only Mary Maddox could dream of attaining."

The effect of such a conversation was not to be underrated, especially for a mind that had suffered as hers had done, and it required several hours to give the appearance of sedateness to her spirits, even if they could not bring serenity to her heart. She did not know what to think; she was flattered, tempted, disarmed. She could not deny that the prospect he described held an irresistible attraction for her; having done so little, and travelled so little, to have a life so full of novelty and endeavour! To be at once active, fearless, and self-sufficient — to move, at last, from a state of obligation to one of such brilliant independency! And yet, did she love him enough to marry him? Did she, indeed, love him at all? She had a regard for him, she admired his intellect and esteemed many of his fine qualities, but she also knew him capable of acts that were abhorrent to her principles, and she had challenged and condemned his gross want of feeling and humanity where his own purposes were concerned. Pity the wife who might fall victim to such barbarous treatment, and all the more so as she suspected that, however high she appeared to stand in his regard, he had no very high opinion of her sex in general. If he became her husband, would she not be more than half afraid of him?

With a mind so oppressed, she longed for the calm reflection of solitude, and after a quiet dinner with the Grants, she professed herself equal to a short walk in the park, and having allayed their very natural concerns, she set out at a gentle pace. The harvest moon had already risen, and was nearly at the full, hanging like a pale lantern over the sheep grazing peacefully on the farther side of the ha-ha. On the other side of the valley the labourers were once again at work, and she had no doubt that her brother was present to direct and dictate; Sir Thomas having determined that the improvements should, after all, be completed, Henry had insisted, to Mary’s very great pleasure, on offering his services. Though the triumph and glory of his scheme would never now be realised: Sir Thomas had decreed that the avenue was to remain, in lasting tribute to the daughter he had lost.

How it happened, she could not tell, but Mary found her footsteps were drawn towards the White House. It was not in hopes of seeing Edmund, for she knew that could not be; nor was it to recall what had happened there only a few short days ago. Had she been asked her purpose, she could not have told, she had only a sense of something unfinished, and incomplete. She unlatched the garden gate, and walked slowly across the lawn. The late summer shadows were lengthening under the trees, and she did not perceive at once that she was not alone. He had his back to her, his head resting against the chair, and a rug draped across his knees. It was so like the posture in which she had last seen him, so awful a reminder of what had been, and what might have been, that she stood for a moment, unable to move, her hand at her breast, and her heart full. Perhaps she made a sound, but at length he moved, and half-turned towards her.

"Mrs Baddeley? Is that you?"

She hesitated; then took a step closer.

"No, Mr Norris. It is not Mrs Baddeley."

There was a pause.

"Mary?" he whispered.

She had heard her name from another’s lips not three hours before, and she could not, at that moment, have told if she had longed or feared to hear it now. She went quickly forward, and stood before him.The change in his appearance clutched at her heart. His face was white and pinched, and his eyes had a hectic feverishness that did not seem to be solely the consequence of his recent misfortune; something more profound was amiss. Neither spoke for some moments, then he roused himself, and gestured towards the chair beside him.

"I am so much reduced, Miss Crawford," he said, in a bitter tone, "that I cannot even do the necessary courtesy to a lady by standing in her presence."

"In that case, Mr Norris, I will sit." They remained in silence a moment, but it was not a companionable silence; the minds of both were over-taxed.

"I had not thought to see you here," she said at last.

"Mrs Baddeley was so good as to wheel me to the garden. I wanted to take a last look at the place."

"Last? Are you going away?"

He shook his head. "Only as far as the Park. This house is to be sold, and everything in it. And it will still not be enough — nowhere near enough — to clear away all the claims of my creditors. My father’s wealth derived almost entirely from his estate at Antigua, and it is only now that I have discovered that it has been making heavy losses for a number of years. In consequence I find I have debts far greater than I could ever have conceived of, and no way to pay them with any degree of expedition, except by the sale of all I have."

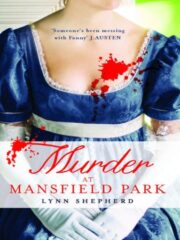

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.