She noted the formal character of his discourse, and felt it at her heart.

"It is a wonder," she said, at length, and with a break in her voice, "that your mother was able to keep up the appearance of affluence for so long."

He smiled sourly. "She has — had — a will of iron. But even she could not endure such a terrible burden for ever; the pressure was too great.That day in the park — the unexpected encounter with Fanny — it was not so very much, in itself. But it brought her to the brink of the abyss. She had already seen the wreck of all her hopes of my marrying Fanny; our debts had mounted to the point of imminent ruin; and now she had to endure contempt and disdain from the very person from whom she expected the utmost deference, gratitude, and respect."

He paused, and gazed across the lawn to where the moon was rising in the late afternoon sky.

"When you spoke to me at the belvedere, I knew at once. When you talked about the blood — the “blood on her hands” — I knew. That day, when I returned from Cumberland, she had not expected me; when I surprised her at the house, she was in a strange mood — excitable, nervous — she could barely keep in one place for a minute together. You know her character, and you know such behaviour to be quite unlike her usual self; I, certainly, had never seen it before. And when I went into the parlour, I found rags in the fire. Blood-stained rags in a fire that did not need to be lit so early on such a warm day. She told me she had dropped a jar in the store-room, and cut her hand, and there were indeed some marks that might have testified to such an incident. But how could I have suspected their real cause? Even later, when it became horribly, indisputably clear, I still could not believe — "

He swallowed, and went on, "When I confronted her, she said she had done it for me — for us. I saw at once that, even if she were the actual perpetrator of the crime, I bore my own terrible responsibility for what she had done. I should have made it my business to enquire into our pecuniary circumstances years ago; had I done so, I would have known the strain under which she had been labouring for so long, and been in a position to take action to alleviate it. Any man of the least decision of character would have done so, and more. How could I, knowing that, allow her to pay the price for my own blindness and incompetency? I did the only thing left to me. I went to Maddox, and confessed to everything."

"Not quite everything. That was how he knew you were not telling him the truth."

He turned to look at her. "So you knew? About Julia? And yet you said nothing."

"I was there when she died. It was impossible not to know. But I was bound by a solemn promise of secrecy. And besides, that day at the belvedere, I believed you to be the murderer. It was your name I had heard on Julia’s lips — it was you I thought had killed her. To keep her from betraying you."

His astonishment appeared to be beyond what he could readily express; he stared at her, then looked away. "There is a fine irony here, could I but appreciate it. Here I have been, thinking you despised me for a fool, a coward, and a dupe, and all the time you believed me capable of killing two defenceless young women in the most brutal, cold- blooded manner." He laughed, but it was a chill and hollow sound. "I should, I suppose, be flattered you deemed me capable of acting with such resolution! And yet, believing that, you trusted yourself, alone, in my company, that day at the belvedere. You took such a terrible risk — merely to warn me?"

Mary shook her head. "I do not think I really believed you guilty. I longed to hear you give a plausible explanation — to tell me some new fact that would prove you innocent."

"And yet no such fact was forthcoming. Indeed, your worst fears must only have been confirmed, when you heard of my subsequent confession."

"I do not wish to speak of that," she said with a sigh. "It is past, and should be forgotten."

"And you wish to think only of the future." It was a statement, rather than a question.

"I do not take your meaning."

"Come, Miss Crawford. The housemaids at the Park can talk of little else, and in my pitiful invalid state I cannot easily escape from their chatter. Mr Maddox is, I gather, growing extremely particular in his attentions."

She flushed, but would not meet his gaze. "I have received a proposal of marriage, yes."

"And when am I to wish you joy?"

"I have not yet made my decision. There are many things to consider."

Had Mary been able to encounter his eye, she might have seen a faint colour rush into his cheeks; the herald of an infinitesimal hope, when all before had been utterly hopeless.

"If things were different, Miss Crawford," he said slowly, "if I were a proper man — a man able to stand on his own feet, and not the useless, vacillating weakling my stepmother always said I was — then I would ask you myself — I would say — " He threw up his hands in anguish. "But how can I do so? Look at me — confined to this damned chair — with no money and no prospect of gaining any. How can I ask any woman — far less a woman like you — to make such a sacrifice? I can live on comfortably enough at the Park — Sir Thomas has been very kind — but a man should give a woman a better home than the one he takes her from, not condemn her to a miserable dependence on the benevolence of others. And it is not only my fortune I have lost. My reputation is gone — quite gone. As far as the world is concerned, I will for ever be a man who confessed to murder, and there will no doubt be some who will always question whether I did not, in fact, commit those dreadful crimes. And if that were not enough, how can I ask another woman to become Mrs Norris, in the shadow of what has happened to the last woman to bear that name?"

They were silent.

"It is true," she said gently, after a pause, "that you are not the happy and prosperous Mr Norris whom first I met."

"In truth, Miss Crawford, I was neither, even then. I did not know, at that time, that my prosperity was as much a chimaera as my happiness. You, by contrast, might now have both. You might marry whom you choose."

"And I do choose, Mr Norris. Do you think my feelings are so evanescent, or my affections so easily bestowed? Do you think I care for what people think? And though I have lived all my life under the narrow constraints of comparative poverty, I am now in the happy position of discarding such wearisome economies for ever. You talked just now of fine ironies; here is another: the fortune that will now provide for me, is the fortune you should have had. Had you married Fanny, as everyone wished, you would be the master of Lessingby now, and not my brother."

He shook his head. "Your words only serve to remind me of my own shame. I should never have allowed the engagement to persist so long. It was cowardice — rank cowardice. I should have spoken to Sir Thomas long ago; had I done so, he would never have allowed the connection to endure as long as it did. I would have been released, and she — she might still be living today."

"But everyone — everything — was against you. Duty, habit, expectation. Such an arrangement — established when you were so young, and supported as it was by your whole family — it would have taken great courage to give it up."

"A man should always do his duty, Miss Crawford, however difficult the circumstances. Indeed, there is little merit in doing so, unless it demands some exertion, some struggle on our part. Long standing and public as was the engagement, I had a duty to her, as well as myself, not to enter knowingly into a marriage without affection — without the true affection that alone can justify any hope of lasting happiness."

His words struck her with all the force of a thunderbolt. She knew — had always known — how wretched she would be if she were to marry a man she did not love, and yet only a few hours before she had been giving serious consideration to just such an alliance. She had even reasoned herself into believing that Maddox might be the only man in the world who could place a just value on her talents, and that they might — as he had insisted — have much in common; not merely a shared literary taste, but a general similarity of temper and disposition. But now the truth of her own heart was all before her. Whatever the inconveniences that might lie before them — whatever the attractions of another course — she loved Edmund Norris still; loved him, and wished to be his wife.

She rose to her feet. "I will detain you no longer, Mr Norris. I must find Mr Maddox, and beg a few minutes’ conversation with him in private."

Had she doubted his affection before, she could do so no longer; the expression of his face sank gradually to a settled and blank despair. It was as if a lamp had flickered and gone out.

"I hope you will be happy, Miss Crawford," he said, in a low voice, turning his face away.

"I hope so too, Mr Norris; but it will not be with Mr Maddox, if I am."

It was said with something of her former playfulness, and when he looked up at her, he saw that she was smiling.

"I have decided to refuse him. After all, how can I marry Mr Maddox when I have already given my heart to another?"

Chapter 23

It was a very quiet wedding. Neither Mary nor Edmund had any inclination for needless ostentation, but it would not have escaped the notice of those schooled in matters of fashion, that the refined elegance of the bride’s gown owed as much to the generosity of her brother, in sending for silks from London, as it did to her own skills as a needlewoman. They had been obliged to wait until the three months of deep mourning were over, but that period had been, all things considered, a happy time; Mary had worked on her wedding-clothes, and wandered about the park with Edmund all the autumn evenings, under the last lingering leaves, raising his mind to animation, and his spirits to cheerfulness. His health improved so well under this agreeable regimen that by the time the couple met at the altar he was able to walk from the church unaided, with his bride on his arm. Sir Thomas was not the only onlooker to observe the effect of real affection on his nephew’s disposition, nor the only one to attribute it to Mary’s lively talents and quick understanding. Mr Maddox had been cruelly disappointed by her rejection, even if he had not ranked his chances of success very high, but his self-control in her presence had been punctilious, and when he departed the neighbourhood some few days thereafter, he had called at the parsonage to bid her the farewell of one who wished to remain always her friend.

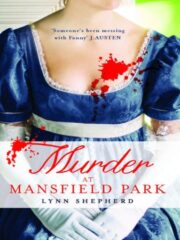

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.