Mary looked at him in consternation, unable to take in all this new information. "Then why in heaven’s name did you not arrest her at once?"

"I needed proof, Miss Crawford, proof. I needed to hear her say it — admit what she had done in the presence of a witness.You were my only hope. I guessed that you would try to see Mr Norris, and having let it be known that he would be moved on Thursday, I made sure that today was your last opportunity. I knew, likewise, that if Mrs Norris was indeed guilty, she would have to intervene to prevent you speaking to him. And knowing how much she hated you, I relied on that hatred to make her voluble."

"And while you waited for this confession of yours, you stood idly by and watched her try to kill her own son?"

For the first time in their acquaintance, she saw Maddox flush. "That, I confess, was an error on my part. I had not expected her to act so soon. I attended the funeral, as you did, having left Stornaway overseeing matters here."

"And he did nothing whatsoever to prevent her?"

"I have not yet had the opportunity to question him fully, but I suspect he did exactly what I instructed him to do. Watch and wait. But I had not, I regret, anticipated either the speed, or the method she would employ. If she resorted to laudanum a second time, I relied on Mr Norris being able to discern the taste; I did not bargain for the dulling effect of curried mutton. No doubt she chose it for precisely that purpose."

"That does not excuse you, Mr Maddox. You put Mr Norris in deplorable danger, and I can never forgive you. He may, even now, be dying at her hands."

Maddox looked grave. "I will regret that, Miss Crawford, for as long as I live. But there is something I regret even more. That I should have so endangered you. You are brave, and you are capable, and I thought that would be sufficient to protect you.To my infinite regret, I found that it was not, and I am more sorry for that than I can say."

They looked at one another for a moment, then she looked away. "You saved my life," she said, her voice breaking.

He smiled gently. "You are most welcome, Miss Crawford. And now I will leave you. I hear a little commotion in the hall, and I fancy your brother has returned with Mrs Grant."

He gave a deep bow, and went out into the garden, leaving her wondering at what had happened, and wondering still more at what was yet to come.

Chapter 22

A week later, Mary was sitting in the garden at the parsonage, a parasol at her side, and a book, unopened, in her lap. It was such a lovely day that her sister had finally relented and permitted her to take the air outside. It was the first time she had been out of doors since the events at the White House, and she breathed the fresh air with the purest delight, noticing how the last flowers of the summer had already started to fade, and the first edges of gold were appearing on the leaves. But her pleasure was not wholly unalloyed. She had not yet been able to visit the Park, whither Edmund had now been removed, and she knew that his recovery was neither as complete, nor as swift, as Mr Gilbert had hoped. They had kept it from her at first, fearing a relapse in her own condition, but Mrs Grant had, at last, admitted that while Mr Norris was now out of danger, the family were apprehensive for his future health. Mary had not yet heard from Mr Gilbert that morning, and when she saw her sister approaching from the house, she presumed at first that she was coming with a message from the physician.

"There is someone to see you, Mary," said Mrs Grant. "I have explained that you have already seen Sir Thomas today, and are still too delicate to receive so many visitors, but he will not be gainsaid."

Mary smiled. "Let me hazard a guess — it is, perhaps, Mr Maddox to whom you refer?"

"The man has scarcely been out of the house since the day you — well, since the day of your accident. I am more than half tempted to start charging him board and lodging."

"I do not recommend it!" laughed Mary. "I am sure our table is better stocked than Mr McGregor’s, so he will very likely take you at your word, and then where will you be?"

Mrs Grant smiled, despite herself. "With an unwanted lodger taking up the only spare room, that’s where I would be. How do you go on with your book?"

Mary smiled. "Not well. It is very entertaining — the author blends a great deal of sense with the lighter matter of the piece, and holds up an excellent lesson as to the dangers of too great a sensibility, but I fear my spirits are not yet equal to the playfulness of the style."

"Well, if you do not wish to read, perhaps you have energy enough for conversation? Shall I fetch Mr Maddox? He says there is something he wishes to discuss with you. I’ll wager it’s about what is to be done with Mrs Norris — there have been messages going to and fro between him and the magistrate for the best part of a week. Mrs Baddeley told me she is to be shut up in a private establishment in another part of the country — some where remote and private, by all accounts, and with her own mad-doctor in constant attendance. If you ask me, she should have paid the price for what she did, but it appears she has quite lost her reason, and become quite raving, and Dr Grant says that even if there were a possibility of her ever standing trial, the jury would be forced to acquit her by reason of insanity. As you might imagine, Sir Thomas will not hear of a public asylum."

"I am not surprised at that. I have acquaintances in London who have visited Bedlam, and I would not wish even Mrs Norris incarcerated in such a terrible place. People make visits there as if it were some sort of human menagerie — they even take long sticks with them, so that they can provoke the poor mad inmates, purely for the sake of entertainment. It is unforgiveable. Sir Thomas would never permit such inhumane treatment, even for the murderess of his own daughter."

Mrs Grant stood up and touched her sister on the shoulder. "You have become quite the daughter to him, these last few days."

Mary blushed. "I think he wished, in the beginning, to thank me for what I have tried to do for the family, and especially for Julia. But since then we have spent more time in conversation, and have found we enjoy one another’s company."

"I am sure that you are more than half the reason why he seems to be becoming reconciled to Henry as a nephew."

Mary shook her head. "I have scrupled to plead Henry’s cause directly — that is not my place. Sir Thomas knows I do not approve of what my brother has done, but I do believe Henry to be sincerely desirous of being really received into the Bertram family, and very much disposed to look up to Sir Thomas, and be guided by him. For his part, Sir Thomas has acknowledged to me that he feels he should bear some part of the blame for what happened — for the elopement, at least. He feels that he ought never to have agreed to the engagement with Edmund in the first place, and that in so doing he allowed himself to be governed by mercenary and worldly motives. He is too judicious to say so, and too mindful of the respect owing to the dead, but I think he had very little knowledge of the weak side of Fanny’s character, or the consequences that might ensue from the excessive indulgence and constant flattery she received from Mrs Norris. As for Henry, if he knew Sir Thomas as I now do, he would value him as a friend, as well as someone who might supply the place of the father we lost so long ago. Sir Thomas and I have talked together on many subjects, and he has always paid me the compliment of considering my opinions seriously, while correcting me most graciously where I have been mistaken. I admire him immensely."

"As he does you, no doubt. And as Mr Maddox does also," said Mrs Grant with a knowing look. "Good heavens! That gentleman will be wondering where I have got to! I will shew him into the garden, and fetch you something to drink from the kitchen. And then I must return to unpacking the new Wedgwood-ware. The pattern is pretty enough, in its way, but I think they might have allowed us rather larger leaves — one is almost forced to conclude that the woods about Birmingham must be blighted."

Despite all her other cares, Mary could not but laugh at this, and she was still smiling a few minutes later when Maddox appeared, carrying a tray and a pitcher of spruce-beer.

"I come bearing gifts," he said, "but I am not Greek, and you need not fear me."

"Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes. I did not know you read Virgil, Mr Maddox."

"And I did not know you read Latin, Miss Crawford. There is a good deal, I suspect, that we do not yet know of one another."

Mary noticed that "yet", but she did not remark upon it.

"My sister says there is something you wish to discuss with me?"

"Quite so. May I?" he said, indicating the chair.

"Of course. Pray be seated."

He sat for a moment, looking at her face, and she became self-conscious. The wound had started to heal above her eye, but there would always be a scar. It was little enough in itself, considering what might have been, and she had never prided herself on her beauty alone, seeing it as both ephemeral and insignificant; but she had not yet become accustomed to her new face, and his intent gaze unsettled her.

"My apologies," he said quickly. "I did not mean to stare in such an unmannerly way, only — "

"Only?"

"It occurred to me, just then, that we have a good deal in common, besides a liking for Virgil. And a scar above the left eye."

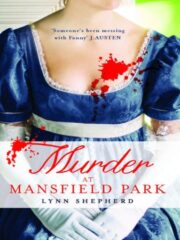

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.