He straightened as she stood. His only hope was to give her the truth.

“I have another confession,” he said.

She might have thought he was admitting to other domestic shortcomings, but when she looked at him she became more serious.

“I’ve been wanting to meet you,” he told her. “For quite some time actually.”

He could see she was surprised by this. She blushed a little.

“Is it so difficult to meet someone?” she said.

Perhaps he blushed too. “As horrible as all of this is—and it is horrible—a small part of me is glad that it’s brought you here.”

As quickly as her face had warmed with his words, it cooled in consideration of their larger circumstances. Hurriedly, he asked her to dinner. He hoped she wouldn’t think too hard on the specifics of their situation and consider being with him a disloyalty to Mandelstam or a belittling of his arrest. He hoped she’d say yes as a kind of reward for his own confession. Or perhaps feel sorry for him, as he was attracted to someone who did not yet feel the same way; he could see she had that capacity. Or perhaps—just perhaps—she was attracted as well. He didn’t care which of these might be true; he only hoped there’d be one, and because of it, she’d answer yes.

She agreed to dinner. She made it clear this would only be a meal. There was the letter to discuss, and he had failed—miserably, in fact—on his promise of tea.

The restaurant was smoky and dim and seemed smaller than he’d remembered. The trio playing in the foyer was loud and poorly balanced. He asked if she’d ever been there but he didn’t hear her answer. They were seated in the back near the kitchen; he’d requested a better table but the waiter raised his hands at this impossibility. Bulgakov ordered soup for them both. She thanked him. He knew this by watching her lips shape the words.

The song ended abruptly; it appeared that the bassist had lost a string and was without its replacement. The instruments were put away and the musicians retreated into an alcove to argue with the manager.

The lack of noise seemed to fill his ears and at first when she spoke he couldn’t hear. He leaned closer. He thought she smiled more easily than at his apartment. The candle between them was set in an ordinary dish; it illuminated her face in a way that was particularly agreeable. She repeated herself. She was going to order the sturgeon.

A muffled crash came from behind them, followed by a second, more distinctive shattering of china, and the swinging doors of the kitchen opened and roughly extruded a large man, a patron. He turned unsteadily and appeared at once to both gesture rudely and apologize profusely to those who’d just cast him out. All who were seated turned in curiosity. The doors swung inward then reflexively out again, and the man, who by any standard was inebriated, sprawled against a nearby table as if trying to escape their reach, upsetting a glass of wine on the blouse of the woman seated there. He stared at her bosom as he pushed himself up and muttered that he liked her dress. Her dinner partner threw his napkin to the floor in anger but did nothing else. The drunken man appeared not to notice and catching sight of Bulgakov’s half-amused, half-concerned expression he stopped. His face was ruddy and shiny and loose as a child’s, and he looked at the same time both belligerent and half-asleep. He leaned over Bulgakov and it seemed he might topple on their table as well. At the last moment he swayed back.

“The sturgeon,” he said, nodding, as if he shared Bulgakov’s concerns. He made a face. “It’s inedible.” He gestured toward the kitchen. “I warned them.” He then noticed Margarita. She looked up at him pleasantly, then away.

The man muttered, “Perhaps your appetite lies elsewhere.”

“We’ve not ordered,” said Bulgakov. He kept his voice amicable and gave a conspiratorial air. “We’ll be wary of the sturgeon, though.”

The drunkard turned his attention back to Bulgakov as if trying to understand the meaning of his words, then burst into laughter, and Bulgakov was left with the impression that the man’s amusement lay not in what he’d said but in the fact that he’d tried to converse at all. The man slapped him on the shoulder as he moved away. “You do that,” he said, and he went back to his table. His companion, a younger woman sitting near the front of the room, appeared unaffected by his behavior. She leaned close as he spoke, then, seemingly on cue, looked at Bulgakov with interest, as if she’d just learned he was a test pilot or an amateur parachutist. Someone who might at any moment die an extraordinary death.

“Would you rather leave?” Bulgakov asked Margarita. He hoped she’d say yes. He felt their evening had been blemished in some way.

“What an astonishing person,” she said, staring across the room.

He was surprised by her choice of words and followed her gaze to reassure himself that they were speaking of the same person.

“No—I want to stay,” she added, “—and I have every intention of trying the sturgeon.”

He thought to talk her out of it—bad fish was bad fish even though freely given advice might not always be the most reliable—but she ordered it. Midway through their meal a bottle of wine appeared; according to their waiter, it was given with the apologies of the man who’d earlier disturbed them. A solid vintage, he said, though Bulgakov suspected he knew little to nothing about wine. The cork broke, however, with half remaining lodged in the bottle’s neck, and the waiter’s efforts to retrieve it only resulted in it being pushed back down into the wine. Bulgakov watched it bobbing through the dark glass as the waiter poured.

Margarita held the bowl of the glass in her hand. The wine swirled red along its walls.

Bulgakov hesitated. “I’m thinking of a toast,” he said, lying. He fingered the glass stem. He wanted to say something about her.

“There is only one,” she said. “To Osip’s release.”

With that they drank.

The wine was slightly sour, threatening to turn. As he lowered his glass, the drunkard was standing between them.

“Thank you for accepting my apology,” he said. “Most gracious. May I join you?” He pulled over a chair from the table vacated earlier by the doused woman and settled into it rather heavily. “With sobriety comes regret, I’m afraid.” He seemed somewhat more articulate, though his face was as red as before and his eyes still as glassy. A glass was brought for him.

“Where is your friend?” said Bulgakov.

“Annuschka? She is my neighbor. She is a working girl,” he said. “She must be off.”

“Thank you for the wine,” said Margarita. “It’s wonderful.”

Her assessment surprised Bulgakov. Perhaps she was only being kind. Bulgakov tapped his glass and nodded. “Wonderful, yes.”

But it was clear the man heard only Margarita. Despite his size, he’d draped himself in the chair and over its arm, leaning toward her in a manner that could be considered almost graceful. Bulgakov decided perhaps he wasn’t as large as he’d originally thought; that instead it was his raincoat, grey and unadorned, that provided the effect. For a moment, he had a fantastical imagining of what form the man might actually take beneath it.

Margarita’s words drifted to him through the fog of his thoughts. She was going on at some length about modern poetry, respectfully though at a superficial level as one might adopt with those of a general education. He wondered how they’d come to that subject. He listened as though he had missed some critical connection that was unlikely to be revealed again.

Had the stranger overheard their toast of Osip?

She spoke of Gumilev and Akhmatova. She didn’t appear to notice the man’s stare. They were notorious dissidents, but the man reacted as though she had listed the ingredients for soup.

It was possible—he told himself—that the drunkard was no one in particular.

Margarita continued seemingly unrestrained by such worries and his nervousness increased. He made a noise, and she turned to him expectantly as if he’d disagreed with her.

“Wonderful, yes,” he said again. His words came out weakly.

The man gave a vague smile. He shifted in his chair and attained equipoise between them both.

Perhaps he was no one.

“Is she still alive?” asked the man, referring to Akhmatova. She’d been popular for a time he remembered, then, it seemed she’d vanished—and with this he waved his hand—“like a fad.” Margarita assured him that she was very much alive and still writing.

“Remarkable,” he said. He didn’t sound terribly impressed.

Margarita glanced past him at Bulgakov. Her eyes had brightened with conversation. She seemed not to notice the flatness of the man’s tone.

He looked at Bulgakov. “Are you likewise a poet?” He apparently had little admiration for this, the question asked in politeness.

“He is a playwright,” she said.

The man’s response showed a bit more enthusiasm. He admitted he did enjoy a good play. Had he seen any of Bulgakov’s? He was always reluctant to ask—there seemed to be a great many more plays being written than could ever be performed.

Bulgakov wanted to say that he suspected not, but Margarita answered for him.

“I should think so. He wrote Days of the Turbins.”

It seemed for the first time that night, the man’s reaction was genuine. “So that was you,” he said, with both interest and incredulity. “You are younger than I would have guessed—but perhaps not.” He seemed to appraise Bulgakov. “It struck me as a rather—and don’t take this poorly—but as a personal piece. Well-constructed, though.” He conceded it’d made for an enjoyable diversion. There was an evasiveness to his manner, in the movement of his hands across the table, the adjustment of his position in the chair; Bulgakov sensed a vague dislike or resentment. He was unable to guess its basis.

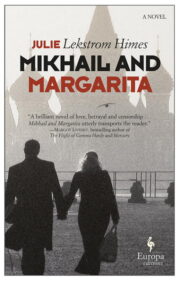

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.