“This isn’t going to work,” he said. He took some ash from the fireplace and smeared it lightly over her chin. “It’s hopeless,” he said, in a kind of wonderment.

She looked at her reflection in the small mirror of his shaving case. She couldn’t capture the entirety of her head in it.

“I can try to scowl like a teenager,” she said.

He studied her; he seemed contemplative of something else.

“Perhaps you should cut it,” she said after a moment. She removed the cap.

He looked away as though her gesture had unsettled him. “If I thought it would help, I would,” he said. He went to manage the luggage. She put the cap back on.

Her other clothes and papers were placed in the hidden compartment of the suitcase. The new papers he produced made her his nephew.

Outside, the air was still. Fresh snow covered the ground and settled on the larger branches. The sky was pale with thin high clouds. The sun, hanging low in the east, was a tepid yellow ball. She got into the car with him. Today, he told her, they would leave Russia forever.

He smiled; they were nearly there.

He started the car. She touched the back of her neck where the chilled air had slipped past the collar of her coat.

They stopped along the roadside briefly. In the distance a town clung to shallow-sloped hills. It was cold and bright with a steady breeze. Ilya had brought some food and she spread a cloth across the hood of the car and laid out the small meal. He set a flask of vodka where their cup would have stood. She took a drink and he smiled at this. It felt like a dare and she drank again.

“When I become too drunk to walk,” she said. “What will you do with me?”

“I will carry you home,” he said.

His use of the word surprised her. She imagined a flat they might share, the cluttered messiness: stacks of books, dishes, shoes about the floor. Both his and hers. Did he make the bed or allow the sheets to collect in a mound at the foot? Would he measure first before hanging a picture or tack it askew? It seemed disconcerting that she didn’t know such things.

She went on more carefully. “And when I become too heavy to manage?”

“I will pitch a tent around us and wait until your drunkenness passes.”

“A tent?”

He seemed to feign surprise. “I carry one for just such occasions.” He touched the brim of her cap; he smiled a little, as though it was remarkable in some way.

“And should I catch a cold from spending the night in your tent?”

“I will feed you tea and honey and aspirin until you are better.”

She imagined them lying together, her pregnant with their child. She imagined him stroking her stomach, cupping the swell, talking to it, sternly at times. Counseling it on the finer points of hockey; assuring that it would know how to skate before it could walk.

And if it’s a girl, she’d mildly protest.

I see that it makes no difference, he’d say. He’d put his daughter against any lineup of boys.

“And if I should become diabetic from the honey and my toes collect sores?” she said.

“I will clean and dress them until they are healed.”

She imagined herself wasted with disease in a hospital bed. She imagined him arguing with doctors, sneaking portions of soups and casseroles past militant nurses. While she slept he would doze in the chair beside her. When she was awake he would tell her gossip of the neighbors, stories to distract. He’d hide his heartbreak from her.

“And if my toes fall off?”

He looked off, at the distant town. “I will give you mine.”

When they were done she gathered the small cloth by the corners and shook the loose crumbs out over the expanse. In the distance, the hills were spotted with shadows cast from high white clouds. She wiped her eyes with the back of her hand.

The train depot in Irkutsk had been built in the time of Tsar Nicholas, shortly before the arrival of its first train in 1898. The ceilings were high and arched; places where its plaster had fallen revealed dark underlying timbers. The stone chosen for its tiled floor was overly porous and its former brilliance had been ground to a toothlike grey even in those few decades. It was poorly heated. Timetables were rarely adhered to and its rows of benches were filled. Some drowsed as they waited. Several grudgingly shifted to make room for them.

A few soldiers milled about though they appeared no older and with no greater seriousness towards life than teenagers. Their uniforms reminded Margarita of the camp guards and she was chilled by the thought that they’d been sent to retrieve her. She laid her glove over Ilya’s and they sat hand in hand as a young couple might, despite their disguise. Margarita knew this could expose them. She hadn’t counted on the pervasiveness of her distress, and she was surprised he tolerated the risk. Perhaps he felt a similar despondency; how could they succeed, in which case, what did it matter? Better to find comfort in their last moments. An old woman swathed in black stared at them. She lifted her hand in what Margarita thought would be a gesture of silence, but instead she crossed herself.

Nearby, a young girl played on the floor with a small and crudely made doll. When she saw Margarita she came over. Holding the doll in one hand, she stroked the sleeve of Margarita’s coat. Her eyes were steel blue and unblinking; short, fair-colored braids could be seen from under a knit cap. She as well seemed unimpressed by Margarita’s disguise. Who was this child—why did she choose Margarita for her attentions? “Someone’s made a friend,” said Ilya; he sounded more curious than concerned. “Where is your mother?” Margarita asked. The girl appeared not to understand or care to be helpful; she seemed to have laid claim to her.

“It’s all right,” said Ilya. His tone had changed. There was a hollowness to it. He was staring at the soldiers.

Where Margarita had counted two, there were now four; they’d coalesced and were moving along the benches, examining the travel papers of those waiting. Only one appeared to have any real interest in this activity; he carried a folded page printed with several photographs. He was shorter than the others, though built broadly through the torso. Despite his youthful face, a day’s growth of beard covered his cheeks. He reminded her of a young bear. A woman was instructed to stand and remove her outer garments. He held the paper alongside her face and studied it, then moved further down the row. Another woman was told to similarly disrobe.

“You should leave,” she said to Ilya.

“Where would I go?” he said.

She thought he meant that there was no world beyond this room; no existence to be counted without her in it. She wanted to tell him how absurd he was being. Then she saw the fifth soldier, standing at the station entrance, rifle in hand.

From the platform, the train’s whistle sounded. The crowd murmured. The soldier carrying the photographs gazed over the heads of those waiting, then climbed onto a bench.

“You may not leave until your papers have been reviewed,” he announced. He seemed unaccustomed to the possession of such authority. His comrades as well gazed at him in mild surprise. He repeated his words in a stronger voice. You will not leave. The crowd seemed to bristle slightly, perhaps at his youth, and he added, as though in a conciliatory way, that no one would miss the train.

He surveyed them once more as he stepped down and Margarita sensed his eye catch and with that there was the turn of decision—should he go straight to her or should he have her wait with the rest; her anxiety growing, he would know. One of the other soldiers had already instructed another woman to stand for examination and he stepped forward with the photographs he carried. It was simpler to go one by one. He would get to her momentarily.

As though he’d gained new confidence, he took his time over this next one. He held the photograph at her ear, then, taking her chin, turned her head to each side. She was young and slim. Would she be mistaken for Margarita? He gestured to a corner of the room and a soldier led her there. He ignored the protests of her family at first, then indicated that they should join her as well. Any remaining conversation was silenced. All eyes followed his every movement, and he, as though aware of this, seemed to harden his expression, his words harsher than necessary. The next young woman was similarly corralled with the first; this time her family let her go. She stood with the others, clutching her hat to her chest, her face stony in its fear, her hair still in disarray after he had had her unpin it.

“You must go,” she whispered to Ilya.

He picked up the child and set her in Margarita’s lap.

Nearby, there was a sudden eruption of sound and motion. A man stood, then stumbled back as though the floor had tipped up on him. Oh dear god—it was Bulgakov! How could this be? Had he seen her? How was it that she’d not seen him until now? All about him seemed unkempt—his clothes flapped loose as he moved, his hair long and uncombed. Was he intoxicated? Had he been there the entire time? He shook his fist in the air, then stumbled forward as though to wield it upon a waiting passenger. A woman shrieked and another man rose to his feet, his arms raised in defense of himself. The soldiers looked around as though skeptical of this disruption separate from their own; a measure of their authority had been lost; a rumble of concern from the other passengers grew. The soldier who carried the photographs nodded to another to go and subdue the drunkard. There was a flash of something in Bulgakov’s hand and a shot was fired.

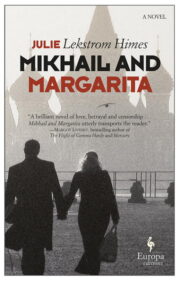

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.