He’d brought clothes for her. Not in her style but she only had those that she’d worn that day. He suggested she consider changing her style. She remembered a particular skirt she’d once owned. She could recall precisely where it’d hung in their apartment in Moscow. She remembered the occasions when she’d worn it. She mentioned it once, as though it was an amusing mystery. “I don’t understand why I miss the thing,” she said. “Was it a favorite of his?” he asked her. She couldn’t remember. Perhaps she’d never known. What did it matter; it was not as though she was going to go back for it. Several miles had passed before she realized that she hadn’t answered. The steppe could do that.

He wore a ring on his right hand. It was a simple band, braided silver. She asked him about it once when he was driving, touching it as his hand held the steering wheel. It’d been a gift, he told her. He’d been engaged at one time. “She changed her mind. I was not the love of her life,” he added lightly. He glanced at her. “It was long ago,” he said, as though she was the one in need of some comfort. Yet the wound seemed still fresh in some way. Perhaps it was the familiarity of the land they traveled which caused old memories to bloom.

“I didn’t know,” she said.

Ilya watched the road unfold. “It was long ago,” he repeated.

It seemed she could not stop touching it. “Was she the love of your life?” she asked.

He smiled a little at the sky ahead as though it was the amusing thing.

It was utterly black outside. She added to the fire. The dark walls seemed to come to life, painted in folk art. Centuries-old and faded, stylized animals and birds and flowers paraded about the perimeter with flourishes of yellow and rust and blue. The images told an ancient story: wolves were chasing an abducted bride. The plot line disappeared behind the cabinet. This was a tale she’d been told as a child. Would the hero slay the beasts in time to save his beloved? She pulled at the cabinet’s corner. It resisted; gripping the floor, too long in its place. She pulled harder. Something was there, written in the wood. She brought a lantern and held it near the wall.

In delicate script, by a woman’s hand, were names in a tidy column, one atop the next, repeated over and over, and beside each, a short line and an age. Ilya at six, Pavel at seven. Ilya at seven, then eight. The lines formed an uneven ladder up the wall. Youngsters bound across the room in hand-sewn overalls, knocking into walls, laughing, taunting as brothers do. Their mother calls them animals. Pavel at ten. Ilya at twelve. There is a girl whose name when spoken will cause Ilya to blush; Pavel takes his advantage with such knowledge. Ilya at fifteen. He finds it amusing that he must bend down to kiss his mother’s cheek. He does this often to show off his stature to her. Pavel at fifteen. There the names stopped. Men are not measured by the hand of their mother.

Margarita turned back toward the fire. Outside, wolves could be heard. The sound didn’t frighten her. She and they would wait together. They would all try not to think too hard.

CHAPTER 39

The concrete steps leading to the small regional police station hadn’t been shoveled. A trail of boot prints had packed down a sullied path. Ilya smoked a cigarette and watched the building from a stand of trees. The glow from an interior desk lamp reflected in one of the windows.

He could hope it would be anyone but him. He crumpled his cigarette against the bottom of his shoe and flicked it into the snow.

The officer seated in the chair looked up as the door opened, then, as recognition widened his gaze, he pushed away slightly and craned his head back. His hair was flecked with gray. His face was broad and flattish in aspect, some ancient Nordic lineage; his cheeks were heavy yet his eyes remained powder blue. He smiled as though pleased for the visit; as though this was all it could be counted as. Ilya measured his expression for its surprise; he didn’t appear to have anticipated Ilya’s arrival, yet Pavel had always been difficult to read.

It startled him how much he resembled their mother.

Their mother told the story of once when they were small, she’d taken a switch in order to punish Ilya for some transgression. But before she could lift the piece against him, she would say, the younger Pavel had stepped between them and, with solemn eyes, asked that he might take the punishment instead. She was amazed, and with every retelling, this seemed new. As it would happen, she’d then conclude, no one was punished that day. Neither of them could remember the event yet they had never doubted her account. Only years later did Ilya reconsider it. He wondered why he’d not been made the hero of that drama. He wondered what she’d read on his young heart that she might want him to believe in some perpetual fealty owed to his brother. He wondered which son she thought she was protecting.

“I can’t believe it’s you,” said Pavel. He touched the top of his head with his hands as though it was necessary in order to contain such news. Abruptly, he stood and hugged Ilya, kissing him on both cheeks and hugging him again. He gestured to the chair beside the desk, easing back into his own.

“How many years has it been?” he asked, as though such a thing must be incalculable.

“Thirty.”

“Thirty.” Pavel shook his head. The number itself seemed tragic. Half a man’s lifetime.

There were only a few things that might estrange a brother from a brother. Perhaps only one. Yet Pavel smiled, as if determined to overcome any obstacle. “I will take you home,” he said. “We will share a meal.”

“Sure. I’ll come,” said Ilya.

They were both suddenly quiet in the face of his lie. Somewhere in the back of the small room, a primus flame hummed. There was no photograph of her on his desk. There was a telephone but Pavel’s gaze passed over it. He could wait to tell her, thought Ilya. In fact, it was unlikely he’d tell her at all. Olga.

The wood grain of the desk was marred by a watermark. It’d been there when it was Ilya’s desk. “You’ve done well?” Ilya asked.

“I’ve had the burden of trying to live up to the reputation of my older brother.”

“Children?” It seemed a required question.

Pavel shook his head. “She couldn’t.” The years of heartbreak that went with that would go unspoken.

“And Olga?” Was this required as well?

“She is fine,” said Pavel. His brief smile sealed that avenue from anything further. “Did you marry?”

Ilya shook his head. What was there to say, other than it was long ago. Even that seemed needless.

Perhaps on this point Pavel agreed. He gestured expansively. “And now my important brother has returned for a visit.”

Ilya had wanted information about Pyotrovich; he wanted it badly enough to risk this trip to the police station. To risk seeing his brother, though Pavel was not a threat. To risk seeing her—even in a photograph. He wondered vaguely if this visit might implicate Pavel in some way. It was unlikely the room was wired. Pavel appeared to have no concerns.

The blowing whistle of a kettle sounded and Pavel got up to prepare tea. Watching him go through the mechanics provided a breath of normalcy. His gait was lumbering, perhaps painful, and Ilya noticed a limp. This was new—new in the last thirty years, and he felt some small guilt for failing to know of it, for his part in the silence between them.

“I wrote you about Mother,” said Pavel, his back turned. There was the mildest sense of rebuke in his voice.

“It found me eventually.”

“I wasn’t certain.”

At the time it’d seemed to have arrived from a different world. “It was nearly summer when I got it,” said Ilya.

“Mail was tricky then.” He paused. “I’ve always wondered when I would see you again.”

In his motions the sense of their mother returned more sharply. The quiet of her disappointment in his setting aside of family, her questioning of this; it would have been a personal thing. When his brother turned, he held a cup in each hand.

Pavel’s gaze seemed to stop short; it focused on his mouth.

“Do you still take milk? I have some powdered in the cabinet,” he said.

When they were children, Pavel had always been able to find him. Even when alone in the forest, desiring the quiet of his own thoughts; even then, Pavel would appear, as though his brother’s wanderings were mapped on his heart.

Pavel set the cups on the desk. One covered the water-mark. He sat down heavily.

How easily they slipped into familiar patterns, as though they’d done this every morning. Time seemed a flimsy thing. What ran in one’s blood that allowed for this?

Pavel sipped his tea. His lips retracted from the hot liquid. “You might want to let it cool a bit,” he said. He glanced at the telephone.

Ilya fingered the cup. It had begun to snow.

For thirty years he’d thought his brother happy. The master of happiness. Supreme in this. It had been enough to keep him away.

But something was wrong. “What happened to Olga?” said Ilya.

Pavel watched the steam rise up from the cup. “She died about a year after you left.”

All that time he’d imagined the world with her somewhere in it. How could he not have known? Behind them the whirring of some small office machine could be heard.

“Pyotrovich has been here twice,” said Pavel, touching the cup’s edge. “Unpleasant man. What is it they say about promotions? There is always one too many?”

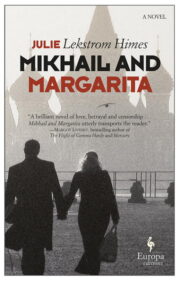

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.