He reached into the backseat and gathered some clothes loosely in one of the pillowcases. She undid the clasp of her skirt and tucked the bundle under her waistband and blouse. She settled back in the seat.

Her arms circled the mound. It was a remembered gesture; a remembered loss. It was her younger self that seemed difficult to recall.

He nodded. “Try to look a bit more matronly.”

Ahead, soldiers moved from wagon to wagon.

The occupants stood to the side while their belongings were examined. When finished, the soldiers moved to the next. They had not yet found what they’d come for.

“Try not to speak,” he said as they watched.

The soldiers went through the cart in front of them. Several had climbed into the back, over irregular forms covered in tarps. They opened crates and bags of various sizes. Off to the side at the verge of the ditch, the woman from before stood watching. Several children clung to her. One of the soldiers broke away, walking toward their car. His rifle slung over his back, he didn’t appear threatening. He knocked on Ilya’s window. Ilya lowered it and the man’s face appeared.

“This is quite a car,” he exclaimed. He grinned openly. He’d get to talk about it for the next few days.

He was Margarita’s age. Startlingly handsome. Eyes that were sharp blue. His hat was pushed back slightly on his head. He looked at Ilya first, then at her. His expression changed slightly. She was the type of girl he’d have pursued. She saw his recognition of this, then his slight puzzlement. Why was she here, with this much older man? He noticed her midsection then, and returned his attention to Ilya as though it’d always been there. “You’ll need to step out,” he said. The car was forgotten.

Margarita opened the door. Ilya’s arm reached across her.

“Would it be all right if my wife remained?” Ilya patted her belly. “I think the midwife is overly concerned, but she wants her to stay off her feet as much as possible.”

Ahead, the woman watched them. Would she notice the change should Margarita get out?

The soldier nodded; of course, if that was necessary.

Ilya opened his door and the steppe’s breeze moved between them as though eager for the chance; it shifted her clothes. She cradled the bulk in her arms protectively.

The soldier asked a question about the car. Ilya got out and closed the door. She didn’t hear his answer.

Several other soldiers approached. She listened to the muffled conversation. The more senior one wanted all of the vehicle’s occupants removed in order to search properly. Ilya tried to appear apologetic, yet shook his head.

She got out of the car. “It’s all right. I’ve been sitting too long.” She hugged the bundle to her. They’d not fastened it in any way and she risked losing it.

The handsome soldier looked concerned for her.

“What an amazing day,” she said to him brightly.

“It is,” he said. As if they were anywhere but along this road.

She sensed Ilya watching this scene, disapproving.

She could tell the soldier that she wasn’t really pregnant. That it was Ilya who’d made her disguise herself. Ilya who’d told her not to speak. Yet she could speak. She could say that all that had happened was his doing. The soldier would believe her. He would believe she was blameless.

The woman ahead saw her; even at that distance, Margarita could see her surprise. She lifted her arms away from the children as though to take a step toward them.

A whiff of fear rose through her. Then she thought, Come to me.

There was a cry from the back of the wagon ahead of them. One of the soldiers standing on the bed had straightened, holding a dark sack, and the soldiers left the car. The woman and her family were surrounded and escorted on foot toward the front of the column. Ilya motioned to Margarita to get in.

“Black market,” he said, once the doors were closed. He seemed relieved, then he looked at her. “Leave that in place until we get past them entirely.”

She touched the mound. It was as if she was incapable of disobedience. Her mouth, her hands were subordinate to him; she could hate them for that.

The column of vehicles began to move. Ilya followed the others. It was a slow exodus.

The soldiers had lined the family up in a row along the top of the ditch. Someone—the husband—had been given a pickax and a shovel. Rifles were trained upon him as he worked to clear the sod nearby.

The woman was watching her younger child, a girl, perhaps three or four years of age, crouched, her dress blossomed about her, picking buds of new clover, her small fingers working them into a chain. The woman called to her; she would want her close, the silkiness of her skin, the comfort of that, but the girl was intent upon a necklace to wear. There came the sound of the ax striking the earth behind her. Her son, older, understanding, gripped her other hand. She dared not move. She called again. She tried to sound sweet. “Come, child, come.” Her daughter pretended not to hear.

Ilya told her to cover her ears. Margarita lifted her hands to her head.

When they stopped for meals, they stood as they ate, sharing a single cup, the corner of the car hood between them. Ilya would distribute their food. She would note the disproportion between them. “I’m not as hungry as you think I am,” she complained, lightly at first.

“You are starved.” This seemed a criticism and she did her best. She sensed they would not leave until she was finished; even should the People’s Army appear over their horizon.

“Please, take some,” she would beg. He would light a cigarette instead and gaze at the scenery as though something in it had changed.

After the family’s arrest, when they next stopped, he took nothing for himself, providing her with a modest portion. She ate several bites, then pushed the rest toward him. “This tastes like sawdust.”

“Taste doesn’t matter,” he said.

He made no effort to push it back; neither did she reclaim it. It lay between them like a forlorn thing.

He lit a cigarette. She as well could pretend disinterest. She sensed that any movement on her part, even the rise of her chest, was in revolt of him. Dry leaves scuttled across the road as though unaware. The breeze pushed her scarf across her cheek; it would set her into motion regardless of what she wanted.

“I won’t eat it,” she said.

He brought the cigarette to his lips.

“Why are you doing this?” she said.

“I’ve told you.”

“I mean why are you doing this?” She extended her arms to the world. He could have left her in that camp.

He gathered the food, carried it to the side of the road, and scattered it across the ditch. He looked for a moment as though he would go further, even stomp it into the ground. He got into the car and started it. He would leave her there, she thought, and she got in quickly.

The car started forward. The forgotten cup flew across the windshield and then away.

“I want to see Mikhail,” she said.

They drove in silence for several hours. He tried an old trail, then after a kilometer he turned and backtracked. He took another, less-likely road. Surrounding fields were still covered in snow; there were intermittent swaths of brush where animals might hide.

“Do you even know where you’re going?” she asked.

Amid the darker grays of a stand of trees, the black timbers of a small hut emerged. The car’s headlights danced across its walls. Its shutters were closed. It appeared abandoned. Ilya turned off the engine and got out.

She stared through the windshield. He pushed the door of the hut with his foot. The lower hinge was broken and it opened only partway. He disappeared into the black interior. The temperature in the car seemed to drop perceptibly and she followed.

Inside, he had lit a match. The orange glow around his hand penetrated little into the darkness, but he seemed to move with foreknowledge to a high shelf built around the room’s perimeter and took down several oil lamps. He lit one, then, with a second match, lit several more. The lanterns extended fingers of light to the walls. There was a hearth, chairs and a table, a cabinet and a bed frame. The place had been left in good order, as if someone had thought to return someday. A small stack of wood remained and he built a modest fire.

He straightened and brushed off his hands lightly. “You should be safe here,” he said.

“Where are you going?” she said.

He gestured to the flames; this wouldn’t last, he told her, and he left as though to gather more. She heard the car engine start and she ran outside.

He’d backed the car across the path they’d taken to the door, then turned the car down the track. Would he leave her? She ran after him. The car bounced over the ruts, gaining speed. Within moments he was gone.

The silent land spread away as if this was all there was. She stared at the road, distant, where it was no longer discernible from the snow. There were no birds; nothing moved. She heard only her own breaths.

There came the howl of a wolf. She went back to the hut. Already the fire was dying.

Once when they’d stopped for petrol, she returned to the car to find a small bundle of daisies on her seat. The wife of the man who operated the distribution site kept a greenhouse. At first Ilya wouldn’t admit to them, then said they’d reminded him of her. He refused to tell her what he’d traded for them. She held the bouquet for a time, then it seemed as though her hands and arms had become dotted with moving grains of sand. The undersides of the petals were covered with spider mites. Ilya tossed the clutch from the window as he drove. She tried to refrain from continuing to examine her arms, rubbing them instead as though it was the chill of the air.

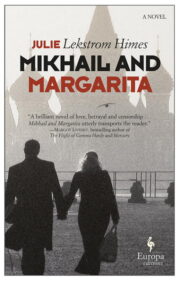

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.