Pyotrovich stood and pulled his coat around him more closely. Even in their brief minutes together, the room had chilled further. In the fireplace, remnants of writing paper, black from combustion, clung to the andirons.

“I can see that better fuel is delivered to you,” said Pyotrovich.

“I have plenty,” said Bulgakov.

“Manuscripts don’t burn,” he said, gently it seemed. “If they did, I could have a different job.”

It had begun to snow and what little light remained was further diminished. Bulgakov did not light a lamp. He stared at the empty fireplace until it was only a dark shape on the wall. Both the vodka and the Nagant were his companions. His hand rested on its cool lines; it felt like the hand of a friend.

If he’d not met Mandelstam that night. Perhaps he would have learned of his arrest the next day. Perhaps later. He’d have gone to Nadya as a grieving friend long after Margarita’s departure. And if he’d seen her at the Writers’ Union (indeed, would she have come?) he’d have recognized her, of course, but it was unlikely that anything further would have transpired. That avenue would have stopped short, like so many unexplored. He’d not have known the difference.

He stroked the Nagant. It wouldn’t hold back the People’s army, but it would do the trick. Yet vodka was his friend as well and he refilled his glass. He listened to the gathering liquid. He didn’t want to die, but he didn’t want to live. Vodka promised to help with this.

Pyotrovich had said that manuscripts don’t burn. Yet people disappear. Whole countries of them.

Bulgakov went to his desk and gathered the final chapters. He knelt by the fireplace. He arranged some of the pages on the andirons; in the darkness, they seemed unaware of their new bed. With a match, he lit a corner. The paper held the flame poorly at first and he moved the match along its edge. As the flames caught, the orange light illuminated the words; he recognized a particular passage. He sat back a little; the flames progressed along the perimeter; then, growing, they leaned inward, cupping the pages. The edges darkened and curled; lifting up, fragmenting, more life to them than they’d ever known. He added more; again, the flames illuminated first, then consumed. The characters who’d lived there were gone. This seemed more than right. They should all disappear.

CHAPTER 38

Ilya had told her they were traveling to Irkutsk. There they would board the train for Mongolia.

He’d had false papers made for them. They were stopped only once. They sat in the car as the soldier reviewed them. Ilya maintained an air of disinterest and boredom. When the soldier bent down to look at her Ilya placed his hand high on her thigh, as if in absent gesture. The soldier straightened, his head disappearing, and concluded his business with them. Ilya’s hand slipped away. She looked out the window and the car started forward.

Later she asked to see them. She made a face at the typeset of her new name. “Who picked this?” Maryanka Vasileyna Solovyova. Ilya didn’t answer right away. He was driving.

“You don’t like it?” He sounded sheepish and in part apologetic. It somehow pleased her that she could do that.

“It sounds like the name of an unattractive girl.”

“No it doesn’t.” He looked to see if she could be serious.

“And you?” she said.

“Boris. Mikhailovich Solovyov.”

So she was married. As though she’d dressed that morning in someone else’s clothes. Of course, it was only paper.

“That is the name of a blacksmith,” she said.

“Perhaps in my next life, Marya.”

She stared ahead. The sky was a hard, steady blue.

“Are you all right?” he said after a moment.

She nodded. “The sun hurts my eyes,” she told him, by way of explanation.

She could hear the voice of Anyuta in her head. It seemed a nuisance memory replaying itself. The girl had been talking on and on about nothing and Margarita had just wanted some quiet to think. You’re not as nice as you look, Anyuta had told her, marching away. Was it a person’s responsibility to live up to the promise of their appearance? An hour later, it’d been forgotten, Anyuta chatting endlessly, but the memory refused to leave her.

She asked Ilya what he thought would happen to Vera and her husband. When at first he was silent, she thought he was considering the question. Then she saw his acute discomfort.

“They had no idea what they were doing,” she said.

“Some effort will be expended to find out if that is true.” He sounded coldly technical, though perhaps self-conscious for that.

She remembered the sound of her feet on the stairs to Vera’s apartment. The wear of the banister under her hand. All of the times she’d joined her at lunch. All of the ways she’d appealed to her nature. Criminal acts, every one.

“You spent time with them too,” said Margarita.

“Any information they provide will put the authorities on the wrong track. At least for a while.” He paused. “If they are forthcoming it might give us an advantage.”

She could still feel Vera’s arm around her waist. Speaking of the daughter she’d always wanted.

He stared at the road as he spoke; it was straight and unambiguous. As though to look instead at her would be a cruel thing. It seemed then he was taking them both to some terrible destination.

They slept in the car at night. Other than that first kiss he’d not touched her. She lay awake under the layers of fur and listened to his restless breathing.

Why writers, he had asked long ago. She’d asked it of herself.

The memory of a particular afternoon came back to her. It’d been raining and Bulgakov had returned to their apartment carrying its chill in the folds of his damp clothes. At first it’d seemed she wanted only to relieve him of his coat, but the fabric of his shirt beneath clung to him in a way that made him startlingly vibrant. She didn’t stop at his coat, his shirt; she wanted to feel the warmth of his skin. He let her; he held his arms slightly apart and quietly watched. He was both passive and complicit. Then she pulled off her own clothes.

Later, she told him he wasn’t such a genius. She was being playful.

“Actually, I am,” he said. He was smiling.

She stopped teasing and became thoughtful. “You’re a genius about people.”

He wouldn’t take her seriously. “I just pay attention. How else does one write?”

“Even the villains have their chance,” she said

“Well—don’t they?”

She reached across the dark car toward Ilya; her fingers stopped short of him.

Why Bulgakov? She thought back to Patriarch’s Ponds—had she known then? Before everything, had she known of those things of which she could be capable? She withdrew her hand.

Write your most flawed character, she wished to him so far away. She squeezed her eyes shut until the darkness turned red. She strengthened her prayer. Take all of your humanity and write your grandest villain, your most foul sinner. Write as though mankind depended on this. And render some parcel of that humanity for me.

The next day shortly before noon, they came upon a line of wagons stopped on the road. The reason wasn’t immediately apparent. The day was fine; the sky promised no difficulties. Much of the snow had melted; clover grew everywhere. Children played along the roadway, chasing each other between the stopped vehicles; mothers stood in the shallow ditch and chatted in small groups. Ilya slowed as they entered the queue, then stopped the engine. Faces turned to them, the car a relative novelty, before returning to other conversations.

Ilya stared over the top of the steering wheel; he seemed certain yet tentative. Perhaps it was nothing. “Stay here,” he said. He looked like he might say more but instead got out and began walking toward the front of the line. Effortlessly he took on the gait of a more common man, ambling, broad-based. He passed a group of children; he ran his hand over the head of one of the older boys playing. The boy glanced up, unperturbed; the old man appeared no different from any of those from his village. She thought—they needed to be forgettable. To disappear among the others. Perhaps he thought that she, like the car, was incapable of such.

There was a knock on her glass. A woman only slightly older bent low and beckoned her, smiling. Margarita lowered the window.

Had she brought something for dinner? asked the woman. Someone had suggested a picnic. The woman eyed the back of the car greedily. Surely someone driving such a vehicle would have something worthy to share. “I’ve never seen a car like this before,” she said.

There was Vera’s food. They couldn’t spare any yet this would be a way to disappear—even for a few hours.

“Is that your husband?” said the woman.

Ilya was returning.

His hands were in his pockets. He appeared to give off a casual air, yet Margarita sensed the urgency in his stride. Something was wrong. She shook her head at the woman. “We didn’t bring anything.” She tried to seem disappointed.

The woman straightened. “How did you find yourself such a pretty young wife?” she said to Ilya.

“Ah,” said Ilya. “But in the meantime I starve. She cannot cook.”

“She will learn,” said the woman. She smiled again at Margarita. “We all do.”

Ilya got into the car and the woman drifted toward the wagon ahead of them.

“They’re searching vehicles,” he said. “I’m not sure for what.” He looked at her then as though cataloguing her every feature. He paused at her midsection. “Can you make it so you appear pregnant?”

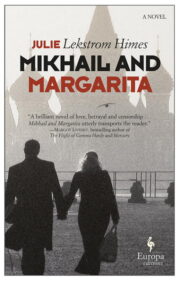

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.