He was to tell her what Pyotrovich had promised, he was to convince her that it was genuine. But what if it was not? And then his next and most terrible thought—how could it be?

She’d been exiled not for her crimes but his. Had any of this changed? Would they let them both go without some warrant? If he vowed not to write, would they believe him? Not to speak—would it be possible?

Pyotrovich wanted only Ilya; the rest of them were a footnote. Promises made would not be kept if for so little as the untidiness of it all.

“Oh, my love.” His voice faltered. There was no answer for them.

“They know about Ilya,” he said.

Fear returned to her face. Certainty as well. She did not question him.

“I’m supposed to tell you that if you turn him in, they will release you,” he said. “That we can then be together.” He paused. “I’m supposed to convince you of this.”

She waited. He knew she would trust whatever he told her.

It seemed impossible to believe that he would never see her again.

“Whatever happens, you mustn’t be caught,” he said. “Promise me.”

The door opened and the guard returned. Bulgakov pressed his pocket watch into her hands. Her expression was a glaze of loss, even as she held it, and then he thought, in some small part there was relief. She could stop pretending that he could give her happiness.

He could stop pretending as well.

CHAPTER 35

Anyuta asked her, repeatedly, what was wrong. She seemed to vacillate between concern and annoyance. What could Margarita say?

She wore Bulgakov’s watch around her neck from a string. It touched her skin between her breasts. Could she wait? The dress was finished. She needed to decide. Eight years—the extent of that gulf was unfathomable.

In addition to its alterations, Vera had taken a scarf and sewn it with a scalloped stitch along the neckline. Up in her apartment nearly every day, Margarita was witness to its transformation. Now it was the last day. The dress hung over the side of the screen. She touched the fabric of the skirt, the scarf, its tidy track of stitches.

Ilya would arrive tomorrow.

Vera’s husband was finishing his breakfast at the table.

“Come up in the morning and put this on,” said Vera. “I’ll make a special lunch for you here. Just for the two of you.”

The manager put his arm around his wife’s waist. “She’s been so excited, planning this,” he said, inclining his head toward Vera.

Vera suddenly noticed his coffee-stained shirt. “Look at this,” she chided good-naturedly. “He’d go about like this if it weren’t for me.” She nodded to Margarita. “See what you may have to put up with yourself.” She tried to shoo him behind the screen to change, but he wouldn’t let go of her until she gave him a kiss.

Margarita looked at the dress as if it was this that overwhelmed her. “I don’t think I can do this,” she said.

“Of course you can,” said Vera. “I’ll hear no other talk.”

“She’s just nervous,” said the manager. “He seems like a stand-up person.” He grinned a little. “I don’t think you’ll need a chaperone.”

Vera gave an exclamation of mock despair. She hugged Margarita, then propelled her to the door. “Don’t listen to him,” she told her. “It’s just a lunch. No pressure.” She regarded her kindly. “Smile and you will light up the room.” She closed the door behind her.

Before descending Margarita paused at the end of the hallway and gazed out across the snowy fields. The crisp expanse was untouched; it glittered in the morning sun. Bordering forests were less distinct; mists hovered among the dark tree trunks, stretching ghostly fingers of white across the perimeter.

She imagined the snow clinging to the hem of her coat as she waded through; she imagined looking back and seeing the path of her choosing manifest to the world.

It was March 3rd, International Women’s Day, and it was decided the inmates would be treated to a single shot of vodka that night with dinner. No one, not the guards nor the prison-workers who went from table to table and provided the measured taste into their cups, could say who had approved the directive or why. The guards joked about the women who’d be loaded up and “jollied” that night. Later, when it was determined the vodka had been laced with ethylene glycol, used as an extender since there was insufficient liquor, a brief investigation was launched by an assistant director of the local Chief Administration of Corrective Labor Camps and Colonies. Bureaucrats arrived at the camp unannounced one morning and interviewed guards and reviewed purchase orders and infirmary records for several hours before disappearing without a verdict. The camp director complained to the head of the district Administration and threatened to write letters up through the chain of officials at the Commission and, subsequently, the investigation was quietly terminated and the assistant director transferred. He would be later arrested on charges of sabotage and sentenced to hard labor within the GULAG system.

Most downed the drink without comment. A brief frown, then the cup was set aside. Some would not finish it. It was too sweet, they complained. They swirled their portions doubtfully. If they feared poison, they didn’t say it aloud. A few, Anyuta in particular, drank their own then filled up on those that had been abandoned. Anyuta went to other tables, allowing the teetotalers to pour theirs in. When she returned and clambered back over the bench, her cup was brimming. Margarita told her this was a bad idea and looked to Klavdia for support. Klavdia watched Anyuta with a strange combination of amusement and disdain.

“Let the girl have some fun,” she said.

Anyuta lifted her cup to Margarita. “Fun,” she said, in pointed defiance. Her already small eyes had narrowed to slits and her nose and cheeks blushed with a glossy redness. “Do you even know what fun is, Comrade?” she asked with a feigned sadness then broke into laughter. She dropped her head onto her handless arm in helpless giggles.

Suddenly, Anyuta looked around, then climbed over the bench. She carried the cup; her other arm was straight and swinging hard, the fabric of the sleeve flapping loosely. Other women stared at her but no one moved to stop her. She jostled against another table unsteadily then continued. She headed toward a cluster of guards standing by the door.

Margarita turned to Klavdia. “There’s something terrifically wrong with you,” she said. The older woman continued to eat. Across the room, Anyuta was talking to the guards. They stood around her in grey jackets and fur-lined hats, nearly double her size, listening intently. One glanced toward the room as she spoke, vigilant, as if the girl might be a deliberate distraction. The others appeared not to concern themselves. Margarita went to her side.

One of the guards was speaking. “What are you asking?” he said to her. He seemed to understand her well enough.

“Isn’t it obvious?” said a larger guard. He was a mountain of a man with a barrel-shaped chest and a face that rippled with old pock scars. His arms were crossed and he loomed over her like a ledge of rock. Anyuta stared up at him.

“I’ve been told a girl can measure the package by the length of the earlobes.” She bobbed back and forth to examine his. “I’d say you were swindled out of a bit or more, Comrade.”

He did not appear to react to her words.

“Really, Anyuta,” Margarita chided. “Our worthy Guards are issued the same standard equipment.” She looked up at the Ledge. “All manufactured with exceptional quality,” she added sweetly.

He seemed no longer interested in Anyuta. “Did you enjoy your vodka?” he asked Margarita. “Did you enjoy it as much as this one?” The other guards were grinning quietly.

Anyuta was furious. She drove her shoulder against Margarita’s, half-turning her. “No one asked you. You always step in. Go back to your precious desk job.” Those last words resounded of Klavdia. Anyuta nearly fell as she stomped away, but recovered herself, her handless arm held aloft. She stumbled against a group of women. The vodka surged from the cup and sprayed across the backs of several. They erupted in protests but she continued past, waving them off with the dripping cup. She disappeared into the corridor that led to the barracks. Margarita turned to follow but the smaller guard grabbed her arm.

“I thought you wanted to inspect our equipment,” he said, jeering at her.

“I’m certain I am unqualified for the task,” she said. She pulled against his grasp but he held her as if by the bone.

“Let her go,” said the Ledge. He appeared to have lost interest in the proposition. He turned to the other guards. One laughed at his subsequent comment. She followed Anyuta into the barracks. The girl was not to be found.

Margarita sat on her bunk board and watched the door. She suspected Anyuta was sick and in the latrine. Sick and drunk and angry. She’d get over all of this by tomorrow. Tomorrow. Margarita got up and looked through her clothes in her box. Tomorrow could well be the day. Could she leave this place? In her box she found a chemise. It was a summery thing. Embroidered in a green and blue pattern. Anyuta would like it. She’d make this a gift to her.

Other women were filing into the barracks. None of them had seen the drunken Anyuta since the dining room. Some looked more concerned than others. One commented on the temperature outside. Klavdia, who had been chatting with several women, said nothing. She turned toward her own bunk board. A planned retreat.

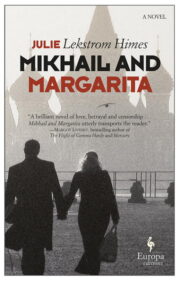

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.