“Are you married?” she asked. The subject was changed. She seemed more cheerful.

Margarita told her no.

“Boyfriend, then.” This wasn’t a question. “He won’t wait. If that’s what you’re thinking. They never do. Perhaps you’ll meet someone here. It happens.”

“Perhaps,” said Margarita. She tried to sound somewhat forlorn. The woman patted the table between them.

“It happens,” she said. “Not hungry? Oh well. I guess that’s understandable.” She carried the dishes to the sideboard. “Don’t forget to leave the sweater when you go tonight. Chances are good you won’t be back.” With those words, she was positively giddy. Raisa was gone. This girl would be gone too. Margarita had miscalculated. The wife now had the ammunition she needed. Her husband could make no argument. She would consider the lunch a win.

Margarita returned to the factory alone. Vera was cleaning her windows. Margarita glanced along the corridors she passed, at the closed doors, a shallow alcove here and there. Places to hide when the guards came for her. At her desk the pile of ledgers requiring her notation had grown. Others around her worked quietly. There was under the desk. They would look there first.

She went back to the apartment. She stood outside the door for a moment. The interior hall was quiet; the midafternoon light was uneven through the windows at either end. She heard a dull movement from within, a piece of furniture across the floor. She took off the sweater and folded it over her arm. She’d failed with the camp doctor but she wouldn’t with the wife. Fear was a better motivator. She knocked, then opened the door.

Vera had stepped down from a chair; one foot was still perched on the seat, the skirt of her dress bunched around her thigh. She reached to cover her bare leg as she lowered her foot. Her first reaction was alarm, even as she recognized Margarita. Margarita shut the door.

“I lied,” Margarita began. “I knew Raisa. I knew her well. She told me things.” She touched the table. “I don’t intend to keep those secrets as she did. Look what happened to her.”

Vera stared at her. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“You have a beautiful apartment,” said Margarita.

The clock ticked.

“We’ve done nothing,” said Vera.

Margarita considered her next words. Nothing terribly specific. She may indeed have done nothing. Her fear would have kept her in check. Not that it mattered. Plenty of people had done nothing.

“How on earth did you come to acquire such lovely things?” Margarita picked up the figurine of a ballerina from the sideboard and inspected it. She set it down in a different spot.

“We’ve done nothing,” Vera repeated, her voice stronger. Partially restored. “I don’t know what you think you know.”

“You’re a clever woman,” said Margarita. She inspected the walls. There was a portion of wallpaper that did not align in pattern with the rest. A poorly rendered repair or something hiding beneath. Margarita smiled and touched the spot. “Prison is filled with clever women.” She became serious again. “Well, one less now, I suppose.”

Vera sat down.

“Raisa—I watched her die. Did you know this?” As if she had a power to be reckoned with. But this was truthful and Margarita envisioned those last struggled breaths. She remembered her own careless words to Anyuta. The way she’d come to have this job. Some would live and some would die. She could try to be unmoved by this.

Vera began to protest but Margarita cut her off. Enough had been said.

“Just beautiful.” Margarita laid the sweater on the table. She smoothed its threads with a gesture of possession. “Thank you for lending this.” She pressed down on the fabric. “I will see you tomorrow.” She took another careful look about the apartment, then departed, the door standing open behind her, and returned to her desk.

At the end of the day, the manager seemed regretful of the pile of remaining ledgers on her desk. She told him she’d take care of them in the morning. He scratched the back of his head, but said nothing other than all right. It’d been her first day, after all. It would be as she said.

Across the room, Vera stood, watching her. Once again, Margarita felt calculation in her every movement. Her desk, in slight disarray, she did not tidy. Her chair, she did not push in. She left them both as she intended to find them. The other woman did not move to object, her expression indiscernible.

On the bus that evening, Anyuta and Klavdia were sitting together. Klavdia was speaking, staring down at her open hand while she pointed to it with her other. Neither Anyuta nor Margarita spoke as she passed; the bus started forward and Margarita grabbed the seatback next to Anyuta’s shoulder. She took an empty seat several rows behind them. Anyuta turned and followed her movements. Only then did Klavdia look around.

That night in the barracks after Klavdia had departed for her side of the room, they lay on their bed boards and Anyuta broke loose with detailed stories from the day. They’d painted ceilings and floors on the factory’s fifth and sixth levels. A dead rat had been discovered in a can of paint where it’d drowned itself. After lunch, Nika and Svetlana had managed to paint themselves into a corner. Her papery voice rose up from beneath and Margarita imagined the factory rooms now haunted forever by their ghostly footprints. But quickly, the stories became about Klavdia. Did she know Klavdia had once been a dancer? She’d even auditioned for the Bolshoi. She’d gone to the University in Moscow for a year but had been expelled for protesting the monarchy. Despite the fact her marks had put her at the head of her class. Even before the men. Her great-grandfather had been part of the plot responsible for the assassination of Tsar Nicholas I. Her birthday was next month. If they could find some thread, she’d promised to teach Anyuta to tat.

Margarita rolled onto her side and whispered into the air. “Does she know as much about you?”

The voice ceased. After a time, Anyuta fell asleep.

The next morning the bus stopped beside the factory. Anyuta, who had sat with Klavdia as before, was asleep, her cheek resting against the older woman’s shoulder. As Margarita passed, Klavdia looked up as though to speak. Her lips parted; Margarita saw the pink of her tongue flicker between her teeth, but then she was silent, her mind changed, and her lips stretched thin into a weak smile. Anyuta snored suddenly, but Klavdia did not move, and Margarita sensed that she herself had lost something and this woman had retrieved it, pocketed it, and refused to give it up to her. As she crossed the walk into the building, the closing of the bus door sounded distant behind her. The snow on either side of the path seemed dirtier than before.

Inside, at Margarita’s desk, the cardigan lay on the arm of the chair. Margarita set it aside and began to work. By the end of the morning, about half of her coworkers had introduced themselves and she had an invitation to join them at lunch in the break room. She met the rest during lunch. There was still no sign of the wife. When she returned to her desk, a red-pink peony in a slender bud vase sat on the corner of her blotter. She touched its petals, wondering where on earth one would lay hands on such a bloom in winter, then saw it was artificial. A metal coil wedged it in the vase. Perhaps pulled from an old hat. Fleetingly, it occurred to her to bring it back for Anyuta—she’d like it. She touched the flower again, with less care this time, then went back to her books. A few hours later she looked up. Vera was standing beside her desk and smiling. Her hands were pressed against her midsection, one atop the other, as if she was trying to hold something in.

“Did you like your flower?” she asked.

Margarita nodded, her words swallowed up in a yawn.

“Did you sleep poorly last night?” she said, her smile melting into concern. She lowered her voice. “Is it hard to sleep?”

“I’m all right,” said Margarita.

“Well, you look nice today anyway.” Vera eyed her hair, then her face. “Very attractive.” She bent closer to her ear and whispered. “I have a surprise for you.”

“I don’t understand,” said Margarita. She patted the pile of ledgers.

Vera motioned with her hand and Margarita followed her to the factory’s vestibule.

The receptionist was speaking with a man. She went then to knock on the manager’s office door. The man turned. It was Ilya. He smiled, as if confused.

“You’re the manager?” he said to Margarita.

It was Ilya.

Vera giggled, covering her mouth with her hand. This was one of their assistants, she explained, a hand behind Margarita’s back. A newcomer to their little family. Ilya nodded and smiled as if he’d never seen her before.

The receptionist returned. The manager would see him now.

Ilya bowed to the women and followed her.

“Handsome, isn’t he?” Vera brought her hands together “I saw him earlier—he’s from one of the factories in the south. Perhaps you’d think a tad old for you, but I’d say well-seasoned. Yes,” she giggled again.

“I don’t think he’s too old,” said Margarita.

“You’re blushing,” said Vera, triumphant.

Margarita could not eat that night or the next morning. She made some excuse of an unsettled stomach and Klavdia looked at her as though she might be infectious. Anyuta helped herself to her untouched portions. Would this be her final meal at the prison camp? The next morning the shoe factory seemed no different than before. The collection of ledgers on her desk had not changed. Other workers arrived with regular greetings. There was nothing that might indicate the propitiousness of the day. She tried to appear busy but could not focus on the ledgers. Midmorning, the manager arrived; he was alone. He greeted the receptionist, then disappeared into his office. Ilya was gone; it was as though she’d imagined him.

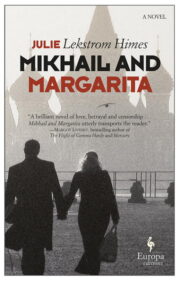

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.