Fedir inhaled; the tobacco was of high quality and he was a little sorry he couldn’t take his time and enjoy it without the distraction of this interview. He was now fully convinced he wanted to move into the Deputy Director’s organization. Any other outcome would result in a decrement in the satisfaction he enjoyed in his job. He sat up straighter. He remembered the stain but did nothing to hide it.

Ivanovich asked his name and he told him.

“That’s Ukrainian, is it not?”

“My mother was Ukrainian.”

“I see.” His tone was neutral. Fedir interpreted his response to be less than neutral. But before he could apologize for his bloodline, the subject shifted again.

“What do you think of Margarita Nikoveyena?”

Fedir was unaccustomed to the use of her name. It was irregular for Ivanovich to go to him for information regarding the prisoner. Fedir hesitated, uncomfortable that this might be perceived as circumventing his own supervisor. This could be some sort of loyalty test. The door to the outer office was still open.

“Wouldn’t you do better to review this with Deputy Director Petrenko?”

Ivanovich’s expression stiffened slightly. Fedir hastened to answer the original question. This man was still a superior.

“She’s had significant associations with known enemies.” He ticked off a short list. Ivanovich looked impressed. Fedir hoped with him.

“And a longer list of persons of interest,” Fedir went on. “I’m surprised that her case didn’t fall under your purview.” He wanted to say that it would have been his honor to investigate such a case, or any case, within the auspices of his organization. He crossed his leg over the stained fabric.

“What of the playwright Bulgakov?” said Ivanovich. “Have you discussed him?”

“I don’t think there is much there.”

Ivanovich seemed surprised. “She was found in his apartment.”

“But your people have investigated him, and found little, is my understanding.” He wanted to show his diligence to the larger picture.

Ivanovich smiled. “You’re correct. Are you enjoying the cigarette? You may have another if you like, for later.” He opened the case for him.

“Yes, I will,” said Fedir. “Thank you. These are wonderful. Where did you get them?”

Ivanovich didn’t answer his question.

“On the other hand, if interrogators such as yourself don’t pursue these answers, then we will never know.”

“I can question her again,” said Fedir. He was eager to please him.

“Only as you see fit.” His tone was mildly obsequious.

Fedir’s cigarette had acquired a subtle bitterness. He considered setting it aside.

Ivanovich went on. “What do you think Director Pyotrovich has in mind for your prisoner?”

“I don’t know.” He said this, even though he did. His supervisor, Pyotrovich’s subordinate, guarded such information closely, yet nevertheless had trusted him with it.

Ivanovich said nothing as though waiting for a different answer. At the start of their interview, Fedir had felt a bond growing between them. This seemed to have dissipated.

“I suspect he’s going to recommend exile,” said Fedir.

“Really? She’d make an excellent informant. Why lose that advantage?”

“Director Pyotrovich believes there are already too many informants of the literary ilk.” As soon as he said it, he realized that this could be an unpleasant revelation for Ivanovich. “He said he’d rather make an example of this one.”

Ivanovich’s demeanor shifted. “How interesting.”

Fedir felt obliged to provide some defense for these sentiments. Or perhaps simply soften their blow. “Truthfully, I’m not certain she’d make an effective informant.” It was difficult to articulate why. Perhaps she lacked sufficient fear of them. Or failed to show a desire for something they could threaten to take away. It seemed they had little to work with. “Occasionally the process of interrogation reduces the prisoner’s value as an informant.”

He was confused by the Deputy Director’s reaction to his words. He thought he saw a sudden admiration for his effectiveness as an interrogator. But there was something else as well—Ivanovich had retracted slightly into his chair. Behind his admiration, there was what could be described as a detached sense of horror, as one who was observing at some distance the antics of a grossly disfigured creature.

“We’ll continue to work on her, of course,” said Fedir. “Perhaps she can produce.” He tried to sound hopeful of this plan, despite his growing disquiet. The space had become warm. He started to lift the cigarette to his lips, then stopped. He wanted only to escape the room.

“Do you think she is actually an enemy of the people?” said Ivanovich. It seemed the first honest question he’d asked of him; the first question for which he didn’t already know the answer. He asked as if it was a question Fedir needed to consider himself.

The room seemed false. The interview as well. As though the furnishings, the bookcases, the portrait of Stalin had been hastily moved in and put up; that the walls themselves were temporary dressings tacked over the standard blue and white paint of the interrogation cell. If he had looked up, he believed he would see a lightbulb dangling; he’d see the single hook.

He had thought of them together, as a couple. He’d thought of coming home to her at night after work. Bringing her flowers and groceries. He’d thought other such ridiculous things.

“I find everyone is an enemy, if I look hard enough,” said Fedir.

Ivanovich seemed not at all surprised nor angered by the impertinence.

Fedir tamped out the remainder of his cigarette. He bowed and left the office. He left the building. He didn’t return to work the next morning, complaining of a head cold. Several months later, he passed away suddenly. The NKVD reported it as a mishap with an electrical appliance.

CHAPTER 25

The appointed time of their meeting had passed for the third straight day yet Bulgakov continued to wait at the small white-clothed table which abutted the front window of a tearoom located several blocks from Lubyanka. For the third straight day he ordered only a Narzan water and a lime, sliced. The server was an attractive young woman whose face had been disfigured by a well-healed scar that ran the width of her forehead, Bulgakov thought, as if someone, in Shelleyian fashion, had attempted to remove her brain through the top of her skull. She never looked at his face as he gave his request, a pencil held over a wad of paper in her hand, and when she heard it, neither did she write it down. Yet, for the hours he waited, his glass never emptied and each plate of rolled and wasted rinds was quickly replaced by another with more jewellike fruit. She seemed a crude experiment of the State’s, one of engineered industriousness that had ended surprisingly well. He had joked with her that first day: the limes were necessary since he feared scurvy. He could see she did not know what that meant and she did not ask. Who jokes about their fears, he thought and he considered her flat affect and scar as only a doctor would. Afterwards, he asked simply for the fruit and the water.

The street between the tearoom and the prison was crowded with people; streetcars ran according to routine. He watched as pedestrians hurried across the tracks before each passing tram; this could be any city in any country; there was little which particularized the scene to their time and place. Yet he could pick any one of these figures, follow them home, or to their workplace, and craft a story that examined the particulars of that life. Each was specific, personal, important. Each deserved notice in some way.

Another streetcar approached; he saw Ilya’s friend, Annuschka, from the restaurant so long ago. She was driving; she wore the driver’s hat and jacket. He caught the flash of her face; her youthfulness seemed to challenge the authority of the uniform’s gold trim and epaulets. Sunlight flared white across the line of windows; then it passed.

Ilya had called her “a working girl,” a neighbor. Was there more to that relationship? Could it be counted as coincidence that she had appeared, on this street, on this particular day, as though she was only doing her job, following arbitrary rails set into the road, as though there was nothing to witness, to ponder, to report upon?

Bulgakov rubbed his eyes. He was losing his mind. Yet he studied the street again. Strangers’ faces seemed both familiar and foreign. He watched for any that might linger in his direction.

Two hours after the appointed time, that third day, a man crossed the square and entered the tearoom. The bell nailed to the top of the door jangled anxiously.

He went to the counter directly, scaned the display case, and ordered several teacakes. He answered the girl, Bulgakov’s server, that yes, he needed them packaged, then casually inquired of directions to Pokrovskiye Gate. He waited, glancing at the specimens under the glass while she went to fetch the manager. The customer was tall and slim with youthful features, yet his brownish hair seemed to be graying prematurely. Bulgakov pretended disinterest, touching one of the empty rinds on his plate.

The manager appeared from a back room, wiping flour from his hands with a towel tucked into his waistband, and Bulgakov stood and motioned to the server to indicate he was leaving. The manager was marking the top of the display case with a still floury finger as if he were pointing to a road on a map. Bulgakov opened the door and their words were lost in the bell’s sound. Outside the light was curious. A thin layer of midafternoon sunlight was sandwiched between the earth and a low-lying bank of gray clouds. Large spots of rain began to darken the sidewalk. Bulgakov headed toward Patriarch’s Ponds. He dared not take a cab. Drops pelted his shoulders and back as he went.

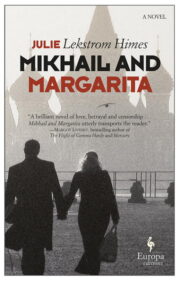

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.