“The French have a cure for a headache,” said Ilya.

“Yes?”

“They call it the guillotine.”

That would be relief from this ride! Who was this man? What was lacking in his life which drove such singularity of purpose? Why had he chosen Bulgakov as the target of his efforts? Bulgakov tried to imagine him as someone’s son or a brother. He tried to imagine a wife or a friend. Ilya had never given any indication that such things didn’t exist, yet somehow Bulgakov felt certain that they couldn’t. If Ilya sensed any of this, he appeared unconcerned. He stared out the side window, his poor joke forgotten, as though the purpose of this shared ride had little to do with Bulgakov.

Across the back of Ilya’s coat was a single blonde hair. Long, like a woman’s. An innocent hanger-on, deposited in the crush of strangers. It glinted in the regular pulse of passing streetlights, disappearing in the intervening darkness as though its existence could never be proven.

“They don’t even see us,” said Ilya. He spoke to the glass. He seemed to marvel at the people outside. He half-turned to Bulgakov. “But we make certain they know of us, don’t we? We have our own particular ways of making ourselves relevant to them.”

The car pulled to the side of the street opposite Bulgakov’s apartment. Above, he could see the light in his window. Margarita passed; she stopped. He saw her face in the window’s frame. Her hair was pinned up; she wore it thus when she was cleaning. She moved off again.

He was relieved she was home; more so than what he knew to be rational. He thought of the questions he would ask her, how he might phrase them. He’d ask about the film first, then about her friend’s opinion of it. Had he met this friend before? Someone she worked with? He would express interest, he hoped, rather than probing curiosity. His questions seemed a temporary solution, lines thrown to her, transient entanglements to keep her near until he could think of a better remedy.

Ilya stared at the window above. “So she stays with you,” he said.

“Some nights.” Nearly every night, he thought, though he was uncertain how that would seem.

“You didn’t bring her to the lecture.”

“She’s generally not interested.”

Ilya’s face was hidden in shadow. “She’s comfortable with you?” The question didn’t concern itself with Margarita so much as it did with Bulgakov, as though his integrity of character made this conclusion questionable. Ilya wanted to know if he was taking care of her. Was he mindful of her welfare? Was being with Bulgakov a good thing for her?

“I’m not keeping her hostage, if that’s what you mean.”

Ilya didn’t react to his indignation. He looked up at the window again as though even the briefest view of her could confirm or refute such a statement.

Ilya had wanted to see her. That had been the reason for the suggested ride. Of course he could have come alone. Sat in front of their building for hours. Perhaps he’d done this already. Perhaps every night. Only tonight, for some reason, he’d wanted Bulgakov to know.

That he desired Margarita?—he probably cared little if Bulgakov knew. Rather, that regardless of how he might feel about it, they were not so dissimilar.

Bulgakov got out of the car and crossed the street. At the building’s door he thought to turn back. To tell him that in fact, yes, she loved him.

He pulled open the door instead and went upstairs. He needed to know if she did.

CHAPTER 18

She was removing the curtains from the windows. Panels of material lay on the floor in untidy piles and the night sky, grey-orange from the city’s light, now hung on their walls like uncertain art. She was on a chair beside the third and final window; she unpinned the fabric from the cord which served as a curtain rod.

“I’m surprised you’re home so early,” said Bulgakov. He shut the door behind him.

Margarita pushed a stray lock of hair from her eyes; it immediately fell back. “The film broke,” she said.

“I’m sorry.”

She put the pins in her mouth as she worked her way across the window.

“Can’t they normally fix that?” he said. “I mean, restart the rest of the film?”

She took the pins from her mouth. “I meant the projector broke. The bulb.” The curtain fell to the floor. She put the pins on the sill then started on the last panel.

“They didn’t have another?”

“I guess not.”

“So the film is O.K.”

“I guess so.” She sounded tired.

He really wanted to stop. “Do you need some help?” he asked.

The curtain dropped next to the other one. He offered his hand as she climbed down from the chair.

She asked nothing of his evening, of the lecture, its attendees; of those he might have conversed with, flirted with, longed for, as though she was indifferent—and, he thought, stubbornly indifferent, sticking to this stance as if she would teach him indifference—and in this she seemed even more guilty of some concealment. He was closer than he’d ever been to achieving his dream—the play catapulting upward to some new and better orbit, yet at the same time and seemingly in some strange and cruel reciprocation, it felt as though she was quickly falling away and there was nothing he could do to stop her.

“What’s your plan with this?” he asked, gently touching a crumpled pile with his shoe. He wanted her to answer a different question. He wanted to know what her plan was for him.

“Laundry.” She sat on the bed and began to unclasp her stockings from their garters.

The windows seemed to harbor a curious gaze into their lives. “And until then?” he asked

“Until what?”

He changed the subject. “I’m sorry the film didn’t work out,” he said.

“You said that already.” One stocking snaked translucent and docile from her hand. She laid it over the chair in front of her.

“You used to like to wear my trousers when you worked,” he said.

“Are you complaining about me?”

“No—I’m just noticing.” He sat on the bed beside her. “I like looking at your legs too.” He wanted to stroke his finger along the curve of her knee, to where it disappeared under her skirt. She stared at her leg as well, as though expecting this too. She seemed ambivalent about it and when he didn’t she went to work on the other stocking.

It was then that he decided to lie.

“I saw Stanislawski tonight.” His mind raced ahead. “I wasn’t going to say anything—I didn’t want you to worry. Perhaps it’s nothing.” He glanced away. “He seems concerned.”

She slowed her movements. “What is it?”

“The censors want another viewing.” He wondered how to modulate the tone of his words. Fearful? Resigned? He maintained a flatness instead; she seemed not to notice.

“It’s already passed. Why another?”

“I don’t know. He didn’t know. Of course he can’t refuse them.” He wondered how she might discover his lie. On the rare chance the director attended a Party event, she was never there.

“This is just muscle-flexing,” she said. “Some bureaucrat trying to show how important he is.” She patted his leg and went back to her stocking.

“There’s something else,” he said. He thought quickly. “There’ve been other visitors from Lubyanka.”

Her seriousness returned. “Ilya Ivanovich?”

“No, not him,” he said.

“He’s been there before. Remember?”

He’d forgotten. They’d seen each other there—or she’d seen him.

“It wasn’t him,” he repeated. “Someone else. I don’t know who.”

“Maybe it’s nothing,” she offered. “Maybe they are no one.”

He was conscious of his own breathing. “Stanislawski doesn’t think so. He’s started rehearsing Hamlet. He’s talking of it as a replacement.”

“Oh, my dear,” she said. Her stockings were forgotten. She touched his hand.

He thought, first, not of the pleasure of her touch. He thought of his betrayal of Stanislawski, who’d stopped all rehearsals weeks before; who’d embraced him warmly. Here he’d delivered an image of the director’s cowardice, of his expediency. He’d besmirched his name in the necessity of a lie. To seduce a woman.

“Perhaps I’m overthinking this,” he said. If he sounded miserable, he thought, this was an honest thing.

She kissed him. He was conscious of the texture of her lips in a way he hadn’t noticed before. As though this was their first kiss—or, he thought then, their very last.

She eased back on the bed, urging him back with her. For a time they simply lay next to each other, still clothed. She kissed him purposefully, as though she could expunge his sad and fearful thoughts. When she went to unbutton his shirt, he started a little.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

“Whatever for?”

What was he sorry for? Her head was bent slightly against the pillow as she worked. He was sorry that somehow she needed to feel pity in order to find love for him.

“I’m sorry you have to worry,” he said.

She brought her face close to his, her expression resolute, and for a moment he was uncertain of what she intended. Her lips touched his and she filled his mouth with her tongue, as though to fill it with something other than words. It seemed, then, gloriously full. He began to pull her clothes from her. Flesh-to-flesh—he couldn’t be close enough. Somewhere below, he heard what sounded like the distant tattling of fireworks; the fabric of clothes ripping. It grew louder.

Later, they lay together, her cheek against his shoulder. He touched the smoothness of her stomach; he spread his hand, his fingers wide, over it.

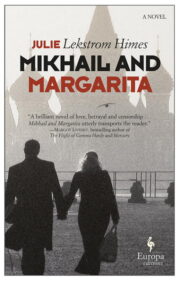

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.