What had caused the man in the painting to enter the jungle that afternoon, the declared realm of the tiger? There was no weapon in sight. Bulgakov imagined him empty-handed, sun-dappled leaves brushing his shoulders as he left the well-trod path.

“The address of your domicile?”

What of his planned course? Were those goals yet worthy? Or had he garnered a new faith? One that called to him from the shadows. One that promised a different reward; that exacted a more certain tribute.

The clerk repeated the question. Ilya raised his head. The clerk appeared to recognize this motion and ceased his questioning. The room was quiet for several moments.

“My apologies,” said Ilya. “My head is splitting.” It wasn’t clear to whom this was intended. “Vasily is here simply to take notes. This isn’t a formal inquiry. Call it a conversation. You don’t mind?”

Beneath the table, Bulgakov pressed his hands together. His arms were lost under its sharp edge; he saw the braided scar it’d made across the chair’s arm. He tried to sound unconcerned. “I’m still not certain why I’m here,” he said.

From the darker shades of the jungle, a pair of yellow eyes glowed. The creature drew him in with its sympathy, its desire. It understood him, loved him for what he really was. It was the tiger after all. We hunt what we love, wouldn’t you agree?

He could hear the predator’s breathing before he saw it, more rapid than a human’s. Its life force exceeded that of a dozen men. Nearby the call of an invisible bird plucked the evening air. Other concerns seemed difficult to recall. He no longer wished to deny the tiger. Desire and fear had melded into one. He stepped in further.

Such pain would be brief. Most were the fodder of worms. He could be a tiger’s feast.

“Is this about an overdue library book?” said Bulgakov. The stenotype’s clatter paved over his attempted joviality and he stopped speaking. Ilya waved his hand at Vasily and the secretary left through the same door.

Ilya produced a cigarette case. He offered one to Bulgakov and took one for himself. He lit them both then leaned back in his chair. He studied Bulgakov through a thin coil of smoke, then manufactured a smile.

“I admire you,” said Ilya. “These are challenging times—for writers in particular. This business with Osip Mandelstam for example.” Bulgakov tried to speak and Ilya waved his words away. “You were friends though I would imagine?”

“More acquaintances,” said Bulgakov.

“But you knew him.”

Everyone knew him. Would they arrest them all?

“It must seem what you do is a dangerous enterprise,” said Ilya.

There was an audible ticking from the other room. “I have no particular politics,” said Bulgakov.

“Everyone has their politics.”

Bulgakov threw himself onto the one truth he couldn’t abandon. “I simply want to write.”

“Of course. And why shouldn’t you? Are you working on something now?” It sounded innocent. A question of polite interest.

The room felt warm.

“Something new?” Ilya suggested.

“No—the play consumes all of my time.”

“That’s too bad.” Ilya’s smile changed slightly. Bulgakov couldn’t tell if it was triumphant or sympathetic. “As I said, these are challenging times. I have to wonder what is keeping you here. In this country, I mean.”

He remembered his conversation with Stalin. He could say he’d asked to leave but had been denied, though that seemed a trap. The better answer was to want to stay.

“There’s a lot to leave behind,” said Bulgakov.

“You have a sister with whom you’ve not spoken in several years. A mediocre career—and that is perhaps generous.” He didn’t wait for his assent. “Few friends. There is no disputing these things.”

Bulgakov felt suddenly depressed. “Where would I go?”

“The world is larger than Moscow. Though perhaps you believe there would be difficulties publishing abroad. Or even worse. Your work may be published but no one will understand it. No one, except perhaps another Russian.”

The rapidity of Ilya’s diagnosis seemed to extract air from the room. “I have considered that possibility,” said Bulgakov.

“Do you lack faith in your own greatness? Or in the ability of a foreign audience to recognize it?” His expression appeared to sour a little, as though a bad taste had entered his mouth. “Particularly if it comes to them so heavily accented.”

Bulgakov sensed in the bureaucrat a pointed dislike for him. It went beyond that which might be directed toward his profession; it was something else—something personal. It seemed a slip of a kind. Once again Ilya appeared sympathetic; any trace of a more ominous sentiment was gone.

“I would miss my homeland,” said Bulgakov.

“Nonsense.” Ilya’s voice boomed slightly in the small room. “Expatriates abound. You would have no difficulties. You might even find those willing to read your work.” He seemed momentarily distracted by a page left on top of Vasily’s stenotype. He picked it up; his brow furrowed as he read. “At one point you petitioned to leave,” he reminded him.

“Perhaps I’ve changed my mind,” said Bulgakov.

“Perhaps?” Ilya sounded mildly incredulous. He then changed his tone. “Perhaps. People change their minds all the time. About their politics, their philosophies. Even their gods. This building is particularly adept at helping people to change their minds.”

“I have a play about to open,” said Bulgakov.

“You do,” said Ilya. His tone was neutral, and Bulgakov wondered what he might know about its fate.

“I have—” Bulgakov was suddenly reluctant to continue. “I have—someone.”

Ilya did not answer immediately. “You do.” His skepticism was gone, as though he’d been momentarily disarmed by the words. “In some ways, it would be easier for me if you were to leave.”

Bulgakov was uncertain of what he meant. He remembered the night in the restaurant when they’d met Ilya. He’d had an inhuman quality, and perhaps that was the nature of one in his occupation. Only now there was a sense of regret, a reluctant acceptance of personal loss that was very human. Not all desires were going to be pursued in this lifetime. Did he have a woman? There was no way such a question could be posed.

“I’m not trying to make things difficult for you,” said Bulgakov.

With that, Ilya seemed restored. “Perhaps you believe that only in this country writing is respected,” he said.

There was an echo of Mandelstam. Bulgakov spoke carefully. “Respected or not, it is my home.”

Ilya then seemed to change the subject. “I’ve always wondered: what is the writer’s inspiration? How do you choose which imaginative peak to scale on any given day?”

Again, Bulgakov was surprised by this turn of conversation. “I can’t speak for everyone,” he said. “I suppose it’s an observation of some incongruity in life. Some paradox that I want to explore. The answer to what would happen if…” Ilya’s expression was unreadable. “Perhaps it has to do with my scientific training,” he added weakly.

“Of course,” said Ilya. “You were first a physician. A venereologist—your specialty in syphilis? Your practice in Kiev. Given up, because—why?”

“I suppose I lost my ambition for it.” He’d done nothing to prepare for these questions.

Ilya seemed ready to ask another, then appeared to change his mind. “I feel we have this in common,” he said. “I too pose such questions to the world—questions of what if. For example, what if a passably successful playwright met with such censorship that none of his plays could be produced?”

Bulgakov felt his chest contract slightly. “I should have no idea of that outcome,” he said.

“No? Then here’s another—what if a physician of comfortable means, bourgeoisie means, was faced with the loss of these luxuries at the hands of an invading proletariat army? What then—would he enlist in a failing Nationalist cause in order to protect the old ways? Would he betray his country’s destiny? That should be a fine plot for a story.”

Bulgakov’s mouth went dry. “It sounds rather flat, actually.”

Ilya went on. “And what if this physician, this traitor, seeking to hide from his past, left his home, and turning to another career, found himself still frustrated and pining for the old life—his petitions to emigrate refused again and again. What if he then took every opportunity to infuse his writings with seditious ideas, cloaking them in some guise of literature?” He leaned forward slightly, and now, for the first time, seemed agitated. The ash from his neglected cigarette fell to the table’s surface and noiselessly shattered.

Bulgakov grew strangely calm, even as the waves of accusation became stronger. They had nothing. Otherwise there would have been not a telegram, but agents at his door. This would be not an interview but an interrogation.

The ruddiness of Ilya’s face had deepened. “And what if—Writer—what if the leader of this great country was so taken in that even he failed to see these obvious sentiments, even he was blind to the treachery in the words. What if he protected this writer because he found him entertaining, unknowing of the real damage this spoiler caused? What would happen if this was revealed to him? What then—”

The room seemed to collapse, losing air, until there was space for only the two of them, their faces inches apart. Bulgakov gathered his breath. “Perhaps you should be the fiction writer,” he said.

“You think it fiction?”

“I love my country,” said Bulgakov.

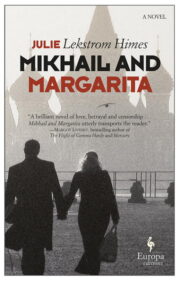

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.