“Have you spoken with Alyosha—about this?” said Bulgakov. His father shook his head.

“My concerns are not of a spiritual nature,” he said. He regarded his son with what seemed like brief forgiveness. For not being more than the child in their relationship. “I see more of myself in you than in your brother.” As if this was some excuse for his choice.

All his father had desired was the company of his son for a few hours, conversation that might fill the drink of time with something other than his own meditations. Not long, he might have thought to say, though he didn’t.

“I wonder what your mother has planned for supper,” said his father, preparing to rise.

“I have to go back to the University,” said Bulgakov.

“Of course you do,” he said. His voice had deepened, the resentment returned.

Margarita had awakened. She pulled the sheet across her and sat on the edge of the bed. In the dim light, undressed as she was, she was stunningly vibrant.

“I’m afraid,” he said. “I’m afraid of dying.”

There was no helping it. Would she answer as he had, so many years before? Would she deny their truth, as he had done? Was it not enough that he had been so unable to bear it in his father that he avoided him entirely? Even when his father had said it plainly. Even then he had denied him altogether.

She still hadn’t moved.

“I’m afraid of disappearing,” he whispered.

“You won’t disappear.” As if by the force of her will she would maintain him.

“You can’t say that.”

She looked away and he was suddenly afraid that she’d never look at him again.

She turned back. “You’ll not disappear.” She seemed to possess new resolve.

He felt her warmth close in, skin to skin, and he thought he could never be parted from her. That would be unbearable, unthinkable. He wouldn’t think it.

He pressed her closer. She could say the words and he would believe them every time.

Like a child, he asked her to say them again.

Bulgakov arrived early at Lubyanka that morning. The foyer of the former insurance company, though several stories high and paneled in rose-colored marble, had been repurposed for office space and was a maze of desks and cabinets of various vintages that were sorely at odds with the drama of the room’s architecture. Those few who were at their desks at that hour looked at him with something between curiosity and concern. Only Committee members or their entourage used that entrance. When it was determined he was none of these he was directed to an empty row of folding chairs along the foyer’s side wall and told to wait. He sat down. A dead moth lay in the corner near his foot. He kicked it under the chair where he couldn’t see it.

On the distant wall, below the room’s peak, a large clock hung. He watched its second hand catch itself at the top of each turn about the dial, taking four to five tries, sometimes more, to achieve its apex. Bulgakov waited nearly an hour by its time then went back to the woman who’d directed him to his seat and asked if she knew her clock was broken. She requested his name and again pointed to the same row of chairs. He told her he’d already seen that view.

“Most who visit are not so eager for another,” she said with a tilt to her head. She seemed to understand that people fell into one of two categories; however, she was still uncertain to which Bulgakov might be assigned. She appeared agnostic to this; no doubt such determinations were made without error. It was her indifference which sapped what little confidence he had and he did as he was told.

The moth lay near his foot again as though it’d moved. He reasoned he could leave. He could say he was going out for a breath of air and never return. He rubbed his palms across the tops of his knees. The cloth felt damp. Perhaps this was a mistake.

A uniformed figure appeared. Bulgakov was uncertain of the insignia. The officer seemed exceedingly enthusiastic and indicated Bulgakov was to follow him. Bulgakov hesitated and the man looked confused.

“You are Playwright Bulgakov?” said the officer. When he nodded the man’s enthusiasm returned. As they passed the woman’s desk, she was preoccupied with a co-worker, smiling at the younger man who leaned against her desk. Bulgakov wanted to point out his escort to her: evidence that he was a respected guest. As they entered the adjacent corridor, she broke into laughter. It sounded incredulous. It seemed to follow him down the hall, as if to say:

You think there are mistakes? Even coincidences? Do you not choose with care every word you lay down, dear Playwright? The moth, the clock, even myself—all have been placed with the same consideration, I assure you. Take nothing for granted.

Her laughter disappeared. The air was chillier than before.

They continued for what seemed to be the width of the block. They passed doors spaced intermittently; some opened into offices. Telephones jangled; the wavering buzz of an intercom punctuated the voices of clerks and secretaries working within. They turned down a second, then, midway, took another turn down a third corridor. Immediately, the atmosphere quieted; the ceiling heightened; the doors, slightly larger, were made of polished wood with carved cornices. The nameplates on each were brass; the names etched in script. After passing several, they came to a painting, hung between two doors, and here the officer stopped. He held out his arm like a docent. This was a Vereshchagin. Truly, he said. He smiled. In this place.

The officer waited patiently, as if inviting Bulgakov to admire the work.

The painting was dominated by the outstretched wings of vultures swarming over the ground. Long shadows of evening stretched from the bottom of the frame. Further in, in the rosy twilight of a secluded glen, a majestic tiger reclined. Between the animal’s arms lay the corpse of a man. Its head and shoulders were in the tiger’s embrace; the creature’s open mouth was poised above him. To the side, other vultures waited; some beat their wings; their eagerness at odds with the languorous gestures of the beast.

“Many of his works were barred from exhibitions,” said the officer. “The romantics of his day had little stomach for his brutality. We Russians,” he smiled. “We always have something to say about our Art.”

The plate under the frame named the piece: Cannibal. The officer went on. “He gives a strange nobility to the victim; don’t you think? There is honor in one’s life culminating in the provision of sustenance to the beast. And even as we recognize the victim, we struggle to see him. In death we are so changed.”

Bulgakov disagreed. The man was not a victim; in his repose, he looked more the willing lover giving himself over to the creature. There was no protest, no scuffle or thrashing of limbs. The man had willingly accompanied the creature into the glen; he’d lain down with it. He had allowed for their differing concepts of love.

The officer told him the painting had once hung in the Summer Palace of Prince Orlov. Now it belonged to the people. He didn’t seem to consider the irony of this. The officer opened the door on the other side. This one had no nameplate.

It was a small antechamber to another office. There was a table with an ashtray and several chairs. The walls were bare. The inner door was closed. The officer sat down and brought out a cigarette case from his breast pocket. He motioned to Bulgakov to sit, then offered him one. The officer lit it for him and they smoked in silence. They were clearly waiting for someone. Bulgakov thought back to the painting in the corridor. The objects in the room, the few that were there, also seemed anticipatory. Like the moth and the clock. He was grateful for the cigarette; it gave him something to do with his hands.

The officer spoke. “I am a fan of yours.” His manner was as a friendly conspirator. “How many times did I see Days?” He took a quick drag, as though this was needed for courage. “I write,” he confessed. He seemed slightly embarrassed. “I keep a journal. Write stories. If you could read one for me, tell me what you think—I’d be quite grateful.”

Bulgakov told him he’d be happy to read his work. Typically this wouldn’t be true, however, in his asking, it seemed that the officer had made up his own mind as to Bulgakov’s innocence and Bulgakov was suddenly and wholly grateful for this and willing to read even the most pedestrian of offerings. The officer was at odds with everything else there. Bulgakov glanced at the inner door.

“I could send it to you,” the officer said.

There was movement from the adjacent room—the closing of an outer door, the sliding of a chair. The officer put out his cigarette; Bulgakov did the same and they stood.

A clerk entered, pushing a small metal cart that held a stenotype; he was followed by Ilya.

Ilya told the officer to leave them and he departed, the details of his manuscript review left unsettled. Ilya took the seat that had been unoccupied. The clerk, a smallish, older man, pulled the remaining chair against the wall, where he then sat. No one spoke as he guided the cart into position in front of him. Bulgakov cautiously took his seat. The clerk began to type. Ilya held his brow in his hand, between his thumb and his forefinger. His eyes were closed.

“State your name,” said the clerk. His voice was nasal as one with a chronic sinus condition.

Bulgakov hesitated. Ilya opened his eyes.

“He knows my name. He’s talking to you.” Ilya had already closed them again. Bulgakov complied. The stenotype rattled anxiously over his words.

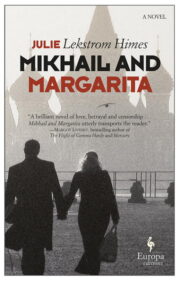

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.