They passed the Moscow Arts Theater. A single workman on a ladder was using a long pole to dislodge the lettered tiles from the theater’s marquis. The word Cabal had already been removed. He, like his play, could easily disappear. Beside the ladder the box of tiles waited, bearing the scrambled hopes of some other writer.

The car slowed. They drove through the gates of the Kremlin. His escorts straightened, then; they faced ahead, alert, as if aware of the possibilities.

They drove past the Cathedral of the Annunciation and the Cathedral of the Assumption to a small, more modern building. They parked and entered. There, his papers were reviewed and he was searched, thoroughly though not impolitely, then conducted on foot to an annex of the Armory. From within, the low long building appeared to be a motor pool, with twenty or more sedans parked at a slant along the interior perimeter, a variety of models, all modern and expensive. In the center of the garage stood a particularly beautiful vehicle, a convertible; it crouched, golden brown, on low haunches. Bulgakov did not know its maker. Its hood was propped open and a mechanic was bent over it. His escorts stopped inside the door; they gave no further instruction. One remained expressionless. The other, the driver, regarded Bulgakov with what seemed respectful curiosity. Across the room, the would-be mechanic straightened and called to him, and the driver looked ahead.

“Bulgakov—lend a hand, man. What? Afraid of a bit of grease?”

It was Josef Vissarionovich Stalin, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Chairman of the Council of Ministers, People’s Commissar for the Defense of the Soviet Union, the “Coryphaeus of Science,” the “Father of Nations,” the “Brilliant Genius of Humanity,” the “Great Architect of Communism,” and the “Gardener of Human Happiness.”

The Great Man laughed and waved him closer.

Bulgakov recognized him, of course, then thought—absurdly, really—he was thinner than his pictures portrayed. A measurable breadth of time seemed to pass before he understood that he needed to approach. Stalin waited, motionless, and—it appeared to Bulgakov—with a manner of tolerance that the powerful will extend toward their supplicants. A sympathy toward those more fragile beings.

Of course he was nervous; even Stalin could understand this.

His sleeves were rolled past his elbows like a workman’s. His hands were streaked in grease. Bulgakov stopped beside the car; its open body lay between them like a bathtub.

Stalin leaned toward him. “Do you know anything about cars, Playwright?”

He shook his head.

Stalin lowered his chin. “Neither do I.” He smiled. “Much to the sorrow of my chief mechanic.”

He wiped his hands with a cloth and closed the hood. He opened the driver’s-side door and extended his hand to Bulgakov to join him. Bulgakov got in. Stalin took the place behind the wheel.

“Perhaps we’ll tinker another day,” he said. He no longer smiled, only started the engine. His words seemed to mean something else.

A strip of light appeared down the center of the far wall; the large garage doors moved apart as if compelled by his fancy, and they drove into the sunny midday. The brightness was momentarily dazzling. They went past palaces and gold-domed cathedrals. Stalin was talking about the car.

It used the Hotchkiss drive, unlike the Phantom I that used the torque tube. He held the steering wheel firmly as he drove. It was a matter of how to propel the car forward. The torque tube carried the force from the traction of the rear wheels turning against the road, to the transmission, and then through the engine mounts to the frame of the car. The Hotchkiss drive transmitted the force directly to the car frame through leaf springs. The Hotchkiss also used two universal joints instead of the one, providing a smoother drive. “You getting this, Playwright? It’s a matter of how we push the earth away.” He nodded. It was he who moved the world; he liked that idea. “You know nothing of cars, do you? You’ve heard of Piaquin? The painter? No? Well you won’t now, either, I suppose. Piaquin was like you.”

Bulgakov had heard of Piaquin.

Stalin turned from the wide boulevard onto a smaller road, tree-lined, driving away from the buildings. Loose rocks from the roadway twanged against the mounts of the body work. The engine droned in a continuous metallic yawn. The road was empty of pedestrians and other vehicles, and the car accelerated; the wind roared in their ears. Stalin raised his voice to be heard.

“Had him under the hood. God knows what the fool thought he was doing.” Stalin released the wheel and held up his hands to Bulgakov, knuckles forward, his fingers folded into his palms. “Chopped off his own fingers in the fan blade.” Stalin laughed, incredulous. He dropped his hands back down to the wheel. “Every single one. Blood everywhere. A damned mess. And the sobs. I told him he could hold the damned brush between his teeth.” He fingered the leather for a moment. “Hold the brush in your teeth, I told him. Should’ve worked. I think it should’ve worked. Sound advice. It would’ve worked.” He glanced at his side mirror. “He managed to tie the noose with his teeth.”

A bird flew low across the road in front of them. There was a muffled slap as it hit the grille. Bulgakov scanned the passing trees; there was no one else around.

“Why does my favorite playwright wish to leave his homeland?” Stalin looked ahead as if the question was for the road. Or the world beyond it. He seemed to wait for the world to answer.

Already he’d seen the letters, or perhaps just that last draft with its final words.

He went on. “‘If a writer cannot publish, perhaps he should go somewhere his work will be accepted.’ Or some such nonsense.” Rather melodramatic, didn’t he think? Self-indulgent as well. This was not a time for self-indulgence.

Bulgakov waited until he was finished. Later, he’d consider that he should have simply agreed with whatever Stalin had said. He’d wonder why he thought he could converse with the Man. By all appearances they were two men. Did they not ride in a car together as two men would? He would wonder if somehow he’d been deceived; that the humanlike appearance of Stalin had duped him somehow.

Instead, he tried to explain. “My work does not pass the censors.”

“Then write what can.” Stalin’s words were stiff. Bulgakov sensed disappointment rather than displeasure.

“I am a satirist,” he said. Strangely, he very nearly added, “Father.”

“I have no use for satirists.”

If Stalin had affection for him, he sensed it in that moment, in those words. There was no apology in them, yet they were more than simply matter-of-fact. They were words of caution from a man who provided no warnings. Even to a recalcitrant wife who’d become a political liability. She’d been found one sunny day like this one, in a pool of old blood, a gun near her hand. The medical examiners were tortured until they agreed to list the cause of death as appendicitis. Afterward they were executed anyway.

Stalin slowed the car and pulled to the side of the road. The sound of the wind stopped.

“Get out,” Stalin said then, cheerfully, and he motioned for Bulgakov to go around to the other side. “Do you know how to drive? I will teach you.” He maneuvered into the passenger seat. Bulgakov hesitated at the door’s lever, but could think of nothing to say and got in.

The steering wheel extended towards him, over his lap, yet seemed uncertain of this arrangement as well.

The road ahead glowed. Trees rose up on both sides. The sky paved blue overhead.

“Are you nervous, Playwright?” said Stalin.

The world stood with mute alertness; it was nervous for him.

He instructed Bulgakov on the placement of his feet. The engine roared momentarily, then stalled. He went through the pedals once more, and again started the engine. This time the car lurched forward.

“Easy, easy, there you go.” The engine purred. Bulgakov looked up at a sizeable tree as Stalin grabbed the wheel sharply. “You have to steer as well,” he said. Bulgakov took his foot off the accelerator and the engine stalled. Stalin restarted it.

After several tries, they were driving along the straightaway in second gear. Bulgakov rehearsed the rhythm of the pedals in his head as they drove. Before them, the road turned abruptly to the right; the wall of the fortress lay in their path. Stalin was talking; Bulgakov wasn’t listening; he was anxious to slow the car without inadvertently heading into the stone.

“You should seek work as a librettist and a translator,” said Stalin. He seemed unconcerned about the barrier in their path. He said he would make the arrangements.

“Should I—” Bulgakov’s feet wobbled over the pedals; the car groaned.

“Well, of course. I imagine the Theatre Director will wish to meet with you. I can’t comment on the specifics of how these arrangements come about. I imagine you will need to ring them up.” He sounded annoyed.

Bulgakov’s world was losing air. The wall ahead grew in size, seeming to taunt. Would he try to run through it? Did he think he could? He’d better stop short, play it safe, live a bit longer. Go home and write a catchy score.

Though, if he wanted to, go ahead—try to break through.

He touched the accelerator and the engine squealed in protest.

“Damn it, man. The brake—”

Bulgakov stamped down. The car shuddered—with uncertainty or relief—and the engine died. Bulgakov stared at the wall.

Stalin gestured toward the door. “Lesson’s over,” he said. Bulgakov went around to the other side as he slid into the driver’s seat. He drove them back toward the garage. The breeze hummed over their heads. He rested one hand on the steering wheel, the other out the open window.

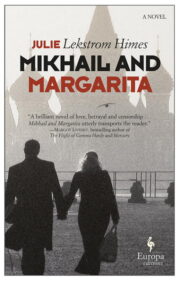

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.