'Why not? They talk of us in drawing-rooms as barbarians. They say we burn villages and shoot the Spanish guerrilleros, but how can any man not give way to fury after seeing such sights? All we want is to give them back a taste of what they have done themselves, make them pay – for all that.' His voice changed suddenly as he added, quite calmly, as though making a simple statement of fact: 'There have been times in that hell when I have thought I was going mad – yet even then, I never managed to forget you. I think I even accepted it all because of you.'

'Because of me?'

'Yes, as if it were a price I had to pay.' And suddenly he turned on Marianne a pair of eyes so blue and innocent that she almost gasped. 'I know that you are far from me by birth, that you are an aristocrat, but all that counts for very little in the Emperor's armies, because there are ways of lessening the distance. Men whose fathers were innkeepers or blacksmiths have been known to rise to high rank, earn pensions and titles and marry duchesses. And however much I might pretend I had gone there to forget you, the truth was that I was hoping to become someone – someone who could address you as an equal. But now, it is all up with that – all up with everything! What can I do to compete with the Emperor? I have not even the right to be jealous of him, while as for bearing him a grudge – that I could never do.'

He turned on his side abruptly, and hid his face in his folded arm. Marianne found herself gazing in perplexity at the shirt covering one thin bony shoulder and a mop of tousled fair hair.

For a second she was unable to speak. The boy's naive and touching confession that he had done his best to hate her and only succeeded in loving her the more, and had undergone the most frightful dangers in the vague hope of one day winning her, wrung her heart. She suddenly wanted very much to be done once and for all with all misunderstandings and get back to the comradeship they had shared on board Black Fish's boat, when they were no more than escaped prisoner and fugitive. She realized that those were the only moments which had really mattered to her and that this odd, rough, unsophisticated boy was dearer to her than she knew.

As she bent over him, she heard him muttering:

'I cannot fight my Emperor – all I can do is go back there, when I am better, and hope that this time it will make an end of me.'

Tears sprang to her eyes and she put out her hand and began gently, very gently to stroke the roughened hair.

'Jean,' she said softly, 'please, don't cry! I do not wish to cause you such unhappiness. I can't bear to see you so distressed.'

'There's nothing you can do about it, is there?' he answered in a muffled voice. 'It isn't really your fault that I fell in love with you … and not your fault at all if you love the Emperor… if anyone's to blame it is myself.' He looked up suddenly and his blue, tear-drenched eyes fastened on Marianne's. 'It is true that you do love him, isn't it? That, at least, was no lie?'

'It is true – I swear it on my mother's memory and it is true that I am very nearly as wretched as you are yourself and you would do wrong to be jealous of him. I may not have the right to love him for much longer. And so – I wish we could be friends now, you and I.'

Jean sat up suddenly and, taking Marianne's two hands in his, drew her down to sit beside him on the bed. He was smiling a little wistfully but his anger had gone.

'Friends? You are sorry for me, is that it?'

'No. It is not pity. It is something else, something deeper and warmer than that. I have met many people since I saw you last, but very few have made me want their friendship. But I do want yours. I – I think I am fond of you.'

'In spite of everything that happened between us?'

Before Marianne could answer, a harsh voice spoke from behind the curtains close to her ear.

'And I should like to know precisely what it was that did happen between you.'

At the sudden appearance of Napoleon, Jean Le Dru gave a cry of alarm but strangely enough, Marianne showed no sign of shock. She stood up quickly, hugging her shawl more closely around her, and folded her arms.

'Sire,' she said boldly, 'I have learned to my cost, on more than one occasion, that listeners hear nothing to their advantage and in general miss the real sense of what they over-hear.'

'By God, madame,' the Emperor said in a voice of thunder, 'are you accusing me of listening at keyholes?'

Marianne curtseyed, smiling. This was in fact precisely what she meant, but he must be made to admit it without an outburst of wrath for which the injured man might suffer.

'Not at all, sire. I merely wished your majesty to know that if you desire any further information as to my past dealings with Jean Le Dru I shall be happy to supply it myself, later on. It would be unkind to question one so truly devoted to his Emperor, and who has suffered so much in his service. I cannot think your majesty has come here with that in view.'

'I have not. I desire to ask this man some questions…'

The curt voice left no doubt of his intentions. Marianne sank into a deep, respectful curtsey and with a smile and a pleasant word of farewell to Jean Le Dru, left the room.

Back in her own apartment, she had little time to prepare herself for the storm she guessed was coming. This time she would not escape close questioning. She would have to tell him everything, except the episode in the barn which nothing on earth would force her to confess. And this not for her own sake alone. She was herself too much in the grip of jealousy not to feel strongly tempted to tell Napoleon frankly that Jean Le Dru had been her first lover. But there would be no enjoyment for anyone but herself in arousing the imperial jealousy and poor Le Dru would very likely have to bear the consequences. Moreover, she was under no obligation to mention an amorous incident which she only wished to forget. It was enough – but Marianne's reflections were interrupted at this point by the Emperor's return.

At first Napoleon merely threw her a glance loaded with suspicion and began striding nervously up and down the room, his hands clasped behind his back. Marianne forced herself to keep calm, and going to a chaise-longue near the fire reclined upon it in a graceful posture, arranging the shimmering folds of her dress becomingly about her ankles. Above all, she must not appear ill at ease, must not let him see the small, nagging fear within her or the unnerving effect his anger always had on her. Any moment now, he would come to a halt in front of her and fire his first question…

Almost before the thought was formulated, he was there, saying in a harsh voice:

'I imagine you are now ready to explain, madame?'

The formal address made Marianne's heart contract. No hint of softness or affection showed in the marble severity of his face – no trace of anger, either, which was infinitely more disturbing. Even so, she managed to conjure up a gentle smile.

'I thought I had already told the Emperor the circumstances of my meeting with Jean Le Dru?'

'Indeed. But your confidences did not extend to the most intriguing parts of what – er – happened between you. And it is just this which interests me.'

'And yet it is hardly worth it. It is a pathetic tale, the tale of a boy in unusual and tragic circumstances falling in love with a girl who could not return his feelings. Out of pique, perhaps, he preferred to listen to certain slanderous stories presenting her as the irreconcilable enemy of his country and of all he held most dear. The misunderstanding grew to such an extent that the time came when he denounced her as an agent of the princes and an émigrée returned to France illegally. That is more or less the whole of what happened between Jean Le Dru and myself.'

'I do not care for "more or less"! What else?'

'Nothing, except that his love changed to hatred because Surcouf, the man he worshipped most next to yourself, dismissed him for what he had done. He entered the army, was sent to Spain – and your majesty knows the rest.'

Napoleon gave a short laugh and resumed his walking up and down, although more slowly now.

'From what I saw, not an easy tale to believe! I'll take my oath that had I not come in, the fellow would have taken you in his arms. I'd like to know then what faddle you'd have told me.'

Stung by the contempt in his voice, Marianne rose, white-faced. Her green eyes met the Emperor's, flashing a greater defiance than she knew.

'Your majesty is in error,' she retorted proudly. 'Jean Le Dru would not have taken me in his arms. It was I who would have taken him in mine!'

The ivory mask had grown so deathly pale that Marianne found herself exulting wickedly in her power to hurt him. Disregarding the menacing gesture he made, she stood her ground as the Emperor bore down on her, eyeing her relentlessly. Nor did she flinch when Napoleon caught her wrists in a grip of steel.

'Per bacco!' he swore. 'Do you dare—?'

'Why not? You asked for the truth, sire, and I have told it you. I was about to take him in my arms, as one would do to anyone one wished to comfort, like a mother with a child—'

'Cease this farce! Why should you comfort him?'

'For a bitter grief – the grief of a man who finds his love again only to see her in love with another, and worse than that, with the one man it is forbidden him to hate, because he worships him! Can you dare say that does not merit some comfort?'

'He has done you nothing but harm and yet you could feel such compassion for him?'

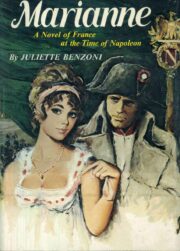

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.