She took a few steps forward to the front of the stage. Her eyes left the imperial box at last and, meeting the conductor's look, she nodded to him to begin the aria again. Then she lowered her eyes while gradually the audience quietened down and the musicians resumed their instruments. Once again, the music began to spin its enticing thread.

But suddenly a movement in one of the stage boxes caught Marianne's attention. A man had just come in and instantly her eye was drawn to him. She thought for a second that it was Jason Beaufort, whom she had sought in vain among the rapt faces before her. It was not him but someone else at the sight of whom Marianne's blood seemed to freeze in her veins. He was very tall with broad shoulders encased in dark blue velvet and thick fair hair brushed in the latest style and the face above the high, white muslin cravat bore a cynical expression. He was a handsome man in spite of the thin scar that ran across one cheek from the corner of his mouth to his ear, but Marianne gazed at him with the incredulous horror belonging to those who have seen a ghost.

She wanted to cry out, to try and overcome the terror which was taking possession of her but no sound came. She felt as though she were in a bad dream, or else going mad. It could not be true. This frightful thing could not be happening to her. At one blow she saw the wonderful, delicate world she had built up for herself at the cost of so much suffering crumble to pieces at her feet. Her mouth opened, gasping for air, but the impression of nightmare became more terrifying while the audience, the imperial box with its dark red roses, the great velvet and gold curtains, the footlights and the conductor's startled face all merged into one infernal kaleidoscope. Marianne put up her hands with a small pitiful movement, trying with all her strength to push the spectre back into the darkness from which it had risen. But the spectre would not go. He was looking at her now, and he was smiling…

Marianne gave one small desperate cry and then collapsed on to the flower-studded stage while, towering above the uproar which arose all about him, her husband, Francis Cranmere, the man she had believed that she had killed, bent forward to look down on the stage and on the slender white form that lay there, twinkling with tiny stars in the stage lights. He was still smiling.

When she opened her eyes, some minutes later, Marianne saw a ring of anxious faces bending over her, against a background of flowers, and realized that she was in her dressing room. Arcadius and Adelaide were there, Agathe was bathing her temples with something cool and Corvisart was holding her hand. Elleviou was there too and Fortunée Hamelin while, towering over them all, was the resplendent figure of the Grand Marshal Duroc, despatched no doubt by the Emperor.

Seeing her open her eyes, Fortunée immediately seized her friend's free hand.

'What happened?' she asked affectionately.

'Francis!' Marianne murmured. 'He was there – I saw him!'

'You mean – your husband? But that is impossible! He's dead.'

Feebly Marianne shook her head.

'I saw him – tall and fair, dressed in blue – in Prince Cambacérès's box.' She struggled to raise herself and her eyes met Duroc's imploringly. The grand marshal understood and disappeared at once. Marianne allowed Corvisart to push her gently back on to the cushions.

'You must calm yourself, mademoiselle. His majesty is in the gravest anxiety on your account. I must be able to reassure him.'

'The Emperor is very good,' she said faintly. 'I am ashamed to be so weak—'

'There is no need to be ashamed. How do you feel? Do you feel able to continue the concert or should we ask the public to excuse you?'

The cordial which the imperial physician had given her was gradually having its effect on Marianne. She felt a little warmth and life return to her body. Now she felt nothing beyond a general lassitude and a slight headache.

'Perhaps I can go on,' she began, a little hesitantly. It was true, she felt strong enough to return to the stage but at the same time she was afraid of the audience, of seeing again the face which had filled her with such terror. In a flash, in the moment of seeing it, she had understood why Jason Beaufort had done all he could to make her go with him and what the mysterious danger was, the precise nature of which he had always refused to divulge. He must have known that Lord Cranmere was alive. But he had wanted to spare her the knowledge. In a moment, perhaps, when Duroc had found him, Francis was going to cross the threshold of this very room and come to her. He was coming now. There were footsteps in the passage. The footsteps of more than one man.

Marianne clung desperately to Fortunée's hand.

'Don't leave me – at all costs, don't leave me!'

There was a knock. The door opened. Duroc was there but the man he brought with him was not Francis, it was Fouché. The Minister of Police looked grave and anxious. With a wave of his hand he dismissed all those gathered about Marianne with the exception of Fortunée, who stayed holding tightly to her friend's hand. 'I fear, mademoiselle,' he said speaking very deliberately, 'that you have been the victim of an hallucination. At the grand marshal's request, I myself went into the Prince's box. There was no one there corresponding to the description you gave.'

'But I saw him! I am not mad, I swear to you! He was dressed in blue velvet – the moment I close my eyes, I can see him still. The people in the box must have seen him!'

Fouché raised one eyebrow and made a helpless gesture.

'The Duchess of Bassano, who is in Prince Cambacérès's box thinks that the only blue habit she saw just after the interval belonged to the vicomte d'Aubecourt, a young Flemish nobleman just recently arrived in Paris.'

'Then you must find this vicomte. Francis Cranmere is an Englishman. He would not dare to come to Paris under his own name. I want to see this man.'

'Unfortunately, he cannot be found. My men are turning the theatre upside down in search of him but so far—'

He was interrupted by three quick raps on the door. Fouché went himself to open it. Outside was a man in evening dress who bowed briefly.

'There is no-one in the theatre, Minister,' he said, 'who seems able to tell us where the vicomte d'Aubecourt can be found. He appears to have vanished into thin air during the uproar which followed mademoiselle's illness.'

There was a silence so profound it seemed that everyone had stopped breathing. Marianne was once more white as a sheet.

'Nowhere to be found! Vanished!' she said at last. 'But he can't have done! He was not a ghost—'

'That is all that I can tell you,' Fouché said shortly. 'Apart from the duchess, who believed she saw him, no-one, do you hear me, no-one had seen this person. Now will you tell me what I am to tell the Emperor? His majesty is waiting!'

'The Emperor has waited long enough. Tell him, if you please, that I am at his service.'

A little unsteadily, but with determination, Marianne rose to her feet and putting aside the woollen shawl they had wrapped round her, went to her dressing table for Agathe to restore some kind of order to her hair. She forced herself not to think of the spectre which had risen from the past to appear so suddenly against the red velvet background of a stage box in a theatre. Napoleon was waiting. Nothing and no-one should ever keep her from going to him whenever he was waiting. His love was the one really good thing in the world.

One after another, her friends left the box, Duroc and Fouché first, followed by the singers and then by Arcadius, though with evident reluctance. Only Adelaide d'Asselnat and Fortunée Hamelin remained until Marianne was ready.

A few minutes later, a storm of applause shook the old theatre to its foundations. Marianne was back on stage.

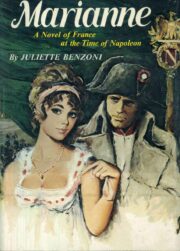

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.