With a little curtsey, Marianne held out the paper sealed with green wax that Fouché had given her. The princess opened it and began to read while Marianne studied her new mistress curiously. Fouché, in describing the wife of the former bishop of Autun, had revealed her age, which was forty-seven. But there was no denying that she did not look it. Catherine de Talleyrand-Périgord was still a very beautiful woman. Tall and Junoesque, with wide, artless blue eyes under thick dark lashes, a mass of warm gold, naturally curly hair, plump lips, parted to show small perfect teeth, a prettily arched nose and charming smile, she had everything a woman could ask for, in a physical sense at least, for her mind was by no means equal to her looks. Without being as stupid as her numerous rivals claimed, she had a kind of naivety which, joined to great depths of vanity, made her an easy target for ill-natured criticism. If she had not been so lovely, no one would have understood why Talleyrand, the most subtle and accomplished man of his time, should have burdened himself with her and there were few women in Paris more derided. Napoleon himself openly detested her and her husband, tired of her childish prattle, barely spoke to her, although this did not prevent him making quite sure that she was treated with proper respect.

The princess's reading of the letter and Marianne's examination of her finished at the same time. The princess glanced up at the girl and smiled.

'I am told that you are of good family, although not bearing a noble name, and that you have received an excellent education. Madame Sainte Croix says that you read well, sing and speak several languages. Altogether, you must certainly do credit to my house. I can see for myself that you are pretty and have considerable natural elegance, I am pleased to say. Your duties here will be very light. I read little but I am fond of music. You will generally bear me company but, when we are together, you will take care to keep always five paces behind me. My name and rank are of the highest and I make it a point to insist on proper respect.'

'Very natural, I am sure.' Marianne smiled, amused by the innocent anarchy of this speech. Fouché had not exaggerated.

Madame Talleyrand might be an excellent creature but she was inordinately proud of being a princess.

'You may go now,' the princess told her graciously. 'I will send for you later. My maid, Fanny, will show you your room.'

Marianne was dismissed with an aristocratic wave of her hand, but the haughtiness of the gesture was softened by the kindness of the smile that accompanied it. Marianne decided that the princess seemed on the whole good natured as well as pretty and this only added to her discomfort. If Madame Talleyrand could only have guessed what the person she welcomed so readily had come to do! No, Marianne felt that she was by no means suited to her employment and, if she could not manage to make her escape as quickly as she should like, she would take care to say as little as possible to her dangerous employer, if anything at all. She was about to withdraw when the princess called her back.

'Wait, child! I must have some idea of your wardrobe. We have company to dine four times a week and entertain most evenings, to say nothing of the Christmas festivities that will soon be on us. I cannot tolerate anything unsuitable in your appearance.' Marianne blushed. The neat clothes she had bought in Brest with the help of Madame de Guilvinec had seemed to her very elegant until today, but, since setting foot in this princely mansion, she had been conscious that she must look very simple.

'I have what I'm wearing, your highness, and two other dresses, one of black velvet, the other green wool—'

'That will not do at all! Especially since the one you are wearing makes you look as though you were dressed in the livery of the house, which is the same colour. Come with me to my bedroom.'

Leaning on the arm of Marianne, who was both amused and embarrassed by this sudden familiarity, the princess swept majestically into a vast chamber adjoining the bathroom. Here, as in the temple of beauty next door, all was pink and gold and the swan reigned supreme, in gilded bronze, on the arms of the chairs and in allegorical paintings. A handsome canopied bed shared pride of place with an enormous cheval mirror flanked by a pair of gilded lamp brackets. All else was buried under an endless sea of open or closed boxes of all sizes and every conceivable colour. Among them, four people stood to attention. Three were women, the first two evidently shopkeeper's assistants, the third a massive female compressed into a garment of apple green quilting with gold frogs, and crowned with a towering edifice of green taffeta and white Mechlin lace.

The fourth person was a chubby little man, rather like a perky sparrow, though at present his chest was puffed out like a pouter pigeon with his own importance. His face was rouged and powdered and he wore an elaborately curled wig that was clearly meant to increase his height. His bow at the princess's entrance would have done no discredit to a dancing master and his capers appeared to Marianne irresistibly funny. The princess, however, instantly released her hold on Marianne's arm and descended on the ludicrous little creature with outstretched hands.

'Ah, my dear, dear Leroy! You have come! And in this appalling weather! How can I ever thank you.'

'I could not fail to deliver your highness's gowns for the Christmas season in person – and I can confidently say we have performed miracles.'

With the air of a conjurer producing rabbits out of a hat, he drew from the various boxes a succession of dazzling gowns, cashmere shawls, scarfs and sashes, while the large green lady, who was none other than Mademoiselle Minette, famous as the purveyor of exquisite lingerie, released a cascade of gossamer shifts, embroidered and lace-trimmed underskirts, veils and the rest. Suddenly, Marianne forgot her private griefs and found herself enjoying this refreshingly frivolous scene with wholly feminine pleasure. Besides, the little Leroy was really very funny.

For a while, Madame Talleyrand forgot her new reader in overwhelming the little man in a quite incredible flood of compliments and civilities, compliments that were very well deserved because the contents of the boxes were marvellous indeed. Gazing in open-eyed wonderment, Marianne forgot the absurdity of his person. Ignorant as yet that the little man was in fact the great Leroy, couturier to the Empress herself, and whose creations were sought avidly by the entire court and even by the whole of Napoleonic Europe, she was amazed that such a person should be capable of creating these fragile works of art. There was one dress in particular, of almond green satin oversown with crystal drops in strange, underwater patterns, that dazzled her utterly. It seemed to shimmer all over, as though with dew, and Marianne found herself dreaming of how wonderful it would be if she were one day to own such a dress. She was just putting out a timid hand to touch the shimmering stuff when she was startled by a loud indignant exclamation from the couturier.

'Her highness wishes me to dress her reader? Me? Leroy? Oh – I'd die!'

Before Marianne had time to feel wounded by the little man's protests, peremptory hands had swung her round on her heels, her bonnet strings were untied and the bonnet itself sent flying into a corner. The young lady assistants hurried to the rescue and whipped off her coat, while Madame Talleyrand expostulated with an indignation at least equal to Leroy's:

'She is my reader, Leroy. And so worth quite as much as all your twopenny duchesses and countesses! Only look at her! I mean to see this beauty properly displayed. It will serve to set off my own.'

There was a thoughtfulness in the couturier's olympian eye as he came and stood before Marianne. He studied her from all angles, walking slowly round her as though observing a monument.

'Take off that frightful dress!' he commanded finally. 'It positively reeks of the provinces.'

Before she could utter so much as a gasp, Marianne found herself standing in her shift and petticoat. Instinctively, she brought up her arms to cover her breast but let them fall again at a sharp tap from Leroy.

'When one has a bosom like yours, mam'zelle, not merely does one not hide it, one displays it, one sets it like a rich jewel! Her highness is right. You are ravishing, even though unfinished as yet. But I can predict that you will be more than beautiful – such a figure! Such hair! Such legs! Ah, the legs, in the present fashion the legs are everything. The gowns reveal them in a way that is almost indiscreet – which reminds me,' turning to the princess, 'has your highness heard? The marquise Visconti, believing her thighs somewhat too well-developed, has got Coutaud to make her a pair of laced stays which she wears one on each leg like corsets! Too absurd! Everyone will think she has wooden legs! But there, she is the most obstinate woman of my acquaintance.'

The princess and the couturier embarked on an exchange of gossip while Mam'zelle Minette shook out a wrap trimmed with broderie anglaise and narrow lavender blue ribbon and laid it over her armchair. But, though he chattered on, Leroy was by no means idle. He took careful note of Marianne's measurements and in the interval of a particularly scandalous story, called out the figures to one of his assistants who copied them gravely into a note book. When it was done and Marianne was still dazed by his flow of words, he told her sharply to get dressed and then asked:

'What should I make for mademoiselle?'

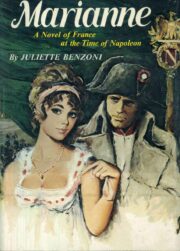

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.