'I was only a few months old when I was taken to England, after my parents went to the guillotine, to my aunt, who was the only close relative left to me. Does that really make me an émigrée?'

'The least one can say is that you did not become one of your own free will. Go on. Tell me your whole story.'

This time, Marianne did not hesitate at all. Nicolas had advised her to be completely frank with the Duke of Otranto. He himself had given the gist of the situation in his letter but since this letter had been left at the Compas d'Or and might well be lost altogether, it was better to make a complete confession. This she did.

When she finished, she was surprised to see her interrogator put his hand into his pocket and take out a piece of paper which she recognized at once. It was Black Fish's letter. Smiling faintly, Fouché dangled it in his long, slender fingers.

'But—' Marianne almost choked. 'That is my letter! Why did you make me tell it all when you knew already?'

'To see if you would tell the truth. Having read this, young lady, I am entirely satisfied with the examination.'

'Oh,' said Marianne. 'I see. The gendarmes must have searched my room. They found that letter and gave it to you.'

'By no means! It did not occur to them. But don't blame them. No, simpler than that, your baggage was brought to me at the ministry at daybreak this morning by someone who was present at your arrest and appeared to feel strongly about it.'

'Monsieur Bobois! Oh, how good of him! He cannot have understood at all and—'

'Don't jump to conclusions, young woman! Who said anything about Bobois? He would certainly never have contemplated the liberty indulged in by your cavalier. The devilish fellow actually burst into my bedchamber, almost had me out of bed! Admittedly, he felt somewhat responsible for your arrest.'

Marianne's curiosity was not proof against these wholly bewildering observations. Forgetting that she was a prisoner and to whom she was talking, she exclaimed 'For the love of heaven, sir, stop playing at riddles with me. I do not understand a single word of this. Who has spoken for me? Who has taken liberties? Who would have hauled you from your bed?'

Fouché extracted a snuffbox from his waistcoat pocket and took a leisurely pinch before finally observing pleasantly:

'Who? But Surcouf, of course! It takes a Corsair to dare to grapple with a minister.'

'But – I am not acquainted with him!' Marianne said desperately, quite overcome at this reappearance in her life of a stranger who certainly seemed a person of no mean importance.

'No, but you seem to have made some impression on him, the more so in that, so far as I can understand it, it was one of his men who denounced you.'

'That is true. The man escaped from the hulks at Plymouth and shared the crossing – and the shipwreck with me and would never believe that I was not an agent of the prince's.'

Whatever promises she might have made to Black Fish, she refrained from any mention of the episode in the barn, thinking with some justification that it was not a matter for the police.

'There are people like that, with fixed ideas,' Fouché agreed pleasantly. He helped himself to another pinch of snuff and sighed.

'Good. Now, all that remains is for you to give me the verbal message sent by Mallerousse. I hope you still remember it?'

'Word for word! He said: 'The former accomplices of Saint Hilaire, Guillevic, Thomas and La Bonté, have landed in the Morbihan and made their way to Ploermel. The general opinion is that they have come to get the money hidden by Saint Hilaire, but that may not be their real objective.'

As she spoke Marianne saw Fouché begin to frown. He got up and resumed his pacing up and down the room. From the things he was muttering under his breath, she gathered with some anxiety that he was displeased. At last he said irritably:

'Mallerousse must have great faith in you to trust you with such important information. I tremble to think what might have happened to you on the way.'

'Is it so important?'

The Minister's keen eyes fastened on her as though to sound her very depths.

'Much more than you can have any idea of – and your question shows me that you cannot be in any way connected with the committee in London, or you would know the persons concerned. At all events, I thank you. You may go and get dressed.'

'Get dressed? But where are my clothes? And what for?'

'Your clothes are over there behind that screen. I need not tell you that you are free. But I should prefer your departure from the prison to go unnoticed as far as possible. So get dressed quickly, and come with me. I am going to the Mother Superior now.'

Marianne did not need telling twice. She hurried behind the screen, a big studded leather affair, green with age, and wriggled out of her prison clothes with joyful speed. She had not worn them long, but it had been long enough to give her a lively distaste for them and it was with a great feeling of relief and wellbeing that she slipped back into her soft petticoat, mulberry-coloured dress, warm coat and pretty hat. The shabby room contained nothing in the way of a mirror but Marianne did not care. What mattered was to be herself again as quickly as possible.

When she emerged, fully dressed, she found herself face to face with a large, authoritative-looking woman in a nun's habit whose face, despite the ravages of fat, still showed the remnants of great beauty. The Superior smiled kindly at her former prisoner.

'I am glad you are to stay no longer with us. I fear the time you have spent here can have left you with no pleasant memories.'

'The time was so short, Mother, that the memory will quickly fade.'

A few more courtesies and Marianne found herself out in the passage again with Fouché, following a nun who led them to a small staircase leading straight down to the entrance where the Minister's carriage waited. The Mother Superior deemed it best that the other prisoners should know nothing of Marianne's departure. They would merely suppose that she had been put in solitary confinement.

'Where are you taking me?' Marianne asked her companion.

'I have not yet decided. You landed on me somewhat out of the blue. I need time to think.'

'Then, if it is all the same to you, please take me where I can get something to eat. I have had nothing since last night and I am dying of hunger!'

Fouché smiled at this youthful appetite.

'I believe it may be possible to feed you. In you get,' he added, putting on his hat as he spoke. A hand, elegantly gloved in pale kid, reached out from the interior of the vehicle to help her up and a deep voice exclaimed: 'Ah! I am glad to see you at liberty again.'

A powerful arm almost lifted Marianne into the carriage and she found herself sitting on velvet cushions facing a smiling man whom she instantly recognized as Baron Surcouf.

The worthy Bobois's sensations of relief at seeing her return escorted by the Minister of Police in person and by his own best customer found their expression in the rapidity with which he set about producing the meal which Surcouf ordered. The morning was by now far advanced and as it was growing somewhat late for breakfast even at the Compas d'Or, Marianne had just time for some small attention to her appearance before sitting down.

Fouché excused himself, saying he had business at the Ministry but that he would expect Marianne at four o'clock in his house in the quai Voltaire when he would inform her of his decision regarding her future. Meanwhile, Marianne and her new friend sat down to a table spread with a clean white cloth and a variety of dishes calculated to satisfy even the most demanding appetite.

Understanding between Surcouf and Marianne had been instant and complete. There was a vigour about the Corsair's square, leonine face which inspired trust while the steady gaze of his blue eyes compelled honesty. His vivid personality exuded energy, enthusiasm and authority. The landlord and his staff hovered around him, anticipating his slightest whim, as eagerly as if they had been the crew of a ship under his command. As she did ample justice to her breakfast, Marianne reflected that, more than anything else, it showed the change which had taken place in her life. This smiling man was a corsair, the very king of corsairs from what people said, and England had no more formidable and determined enemy. And yet, here she was, she, the one-time mistress of Selton Hall, sitting down and breaking bread with him as though they had known each other all their lives. What would Aunt Ellis have said?

She could not have said herself exactly what she was doing there and why this stranger should have interested himself in her affairs to the extent of pursuing a Minister in his own home. Had he some ulterior motive? The truth was that when Surcouf looked at Marianne his face had the dazzled expression of a child who has been given a particularly lovely toy, eyes full of stars yet hardly daring to touch. He blushed beneath his tan when Marianne smiled at him and if, by chance, her hand touched his on the table, he would draw back awkwardly. Marianne was too much a woman already not to find the game amusing, though it in no way interfered with her enjoyment of master Bobois's excellent cooking.

But sharp as Marianne's appetite was, it could not compare with Surcouf's. Dish after dish vanished with a remorseless regularity that was little short of prodigious. Filled with admiration for such capacity, Marianne waited for a break before putting the question that burned on her lips.

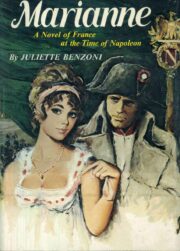

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.