She must therefore see this lofty personage as soon as possible, and that meant drawing as much attention to herself as possible. The silence all about her was unendurable. To keep her spirits up, she thought of Jean Le Dru and of what she would do to him were fate ever good enough to deliver him up to her bound hand and foot. The method worked. Once more wide awake and stirred to a fine rage, Marianne flung herself on the door and began pounding on it and screaming at the top of her voice.

'I want to see the Minister of Police! I demand to see the Minister of Police!'

Nothing happened at first but she went on shouting still more loudly without losing heart. In a little while, there was a pattering of footsteps in the passage and a nun's austere face appeared at the barred peep-hole in the door.

'What is the meaning of this disturbance! Be quiet at once! You will wake everyone!'

'I don't care if I do. I have been wrongfully arrested. I am not an émigrée, I am Marianne Mallerousse and it says so in my papers if they had given me a chance to bring them. I want to see the Minister!'

'Ministers cannot be woken up in the middle of the night for the sake of little girls who lose their temper. Go to sleep! No doubt your case will be dealt with in the morning.'

'If it can wait till morning, I can't see why I wasn't allowed to sleep peacefully in my own bed. The rate your gendarmes moved, you'd have thought there was a fire on!'

'They had to make sure of you. You might have given them the slip.'

'I'm sorry to have to tell you, sister, but you're talking nonsense. I had just taken a room at the inn after a long and tiring journey. Can you tell me why I should have run away again, or where?'

The few square inches of face framed in the black and white headdress seemed to become still more withdrawn.

'I am not here to argue with you about the method of your arrest, my girl. You are in prison. And I am under orders to guard you. Be quiet and try to sleep!'

'Sleep? Could anyone sleep with such a sense of injustice!' Marianne cried in ringing, melodramatic tones. 'I shall not sleep until my cries are heard! Go and fetch the Minister. He must listen to me!'

'He can listen to you just as well tomorrow. Be quiet, now. If you persist in this disturbance I shall have you transferred to a punishment cell where you will be no better off—'

The words carried conviction and since she was by no means anxious to find herself thrown into an even gloomier dungeon, Marianne thought it wisest to lower her voice. But she did not admit defeat.

'Very well! I will be quiet. But mind this, sister. I have something important to communicate to the Minister, something very important indeed – and he may not be best pleased if you prevent me reaching him in time. However, if the Minister's displeasure means nothing to you—'

That it did mean a good deal, Marianne could see from the sudden alarm reflected on the nun's face which, she could have sworn changed colour. The Citizen Fouché, so recently elevated to a dukedom, could not be an easy man.

'Very well,' the sister said quietly. 'I will inform our Mother Superior and she will take the necessary steps tomorrow morning. But, for God's sake, make no more noise!'

She looked round anxiously. In fact, the inmates of the neighbouring cells were awake and the murmur of grumbling voices could be heard on all sides. The silence was peopled and the desert lived, to all appearances much to the wardress's annoyance.

'There!' she said crossly. 'You have woken the whole floor. It will take me a good quarter of an hour to get them quiet again. You deserve punishment.'

'Don't upset yourself,' Marianne said kindly. 'I'll be quiet. But you be sure to keep your promise!'

'I have promised nothing. But I do promise. Now, be quiet.'

The face vanished and the hatch snapped shut. The prisoner heard the nun's voice, loud and firm now, moving along the corridor telling each one to be quiet.

Satisfied with her progress, Marianne returned to her mattress, her ears alert for the various noises around her. Who were they, these women whose sleep she had disturbed, whose dreams she had unwittingly entered? Were they real malefactors, thieves and prostitutes or, like herself, innocent victims of the terrible police machine? She felt an instinctive sympathy for these faceless, complaining voices, simply because they were women. How many of them had suffered, like herself, at the hands of one or more men. In all the books she had read, excepting possibly the frightful story of Lady Macbeth, every wretched woman who came to a bad end was always driven to it by a man.

And so, pondering on these other women, invisible yet ever-present, with whom fate had thrown her, Marianne fell asleep at last without realizing it. When she woke, it was broad daylight, as broad, that is, as daylight could be in a cell in St Lazare, and the sister wardress was standing beside her with a bundle under her arm. Dumped on the bed, this bundle proved to contain a plain grey woollen dress, a cap and fichu of unbleached linen, a coarse shift, thick, black woollen stockings and a pair of clogs.

'Take off your clothes,' the sister commanded sternly, 'and put these on.'

It was a different nun from the night before and suddenly Marianne lost her temper.

'Put on these hideous things? Certainly not! To begin with, I am not staying here. I am to see the Minister of Police this morning and—'

The newcomer's face was expressionless as her voice. It was so large and pale as to be almost indistinguishable from her veil, so that the total effect was something like a full moon, utterly devoid of character. Apparently, however, its owner knew how to obey orders. In exactly the same tone, she repeated: 'Get undressed and put these on.'

'Never!'

The nun showed no sign of anger. Going out into the passage, she took a clapper from her pocket and banged three times. Not more than a few seconds later, two strapping creatures whose uniforms told Marianne they must be two of her fellow prisoners, burst into the cell. In fact, they were so large and strong that but for their petticoats and a certain spareseness of moustache, they might easily have been mistaken for a pair of grenadiers. Moreover, the identical vivid scarlet and high polish of their cheeks showed that the prison diet was by no means as debilitating as might have been imagined and that, for these two at any rate, it certainly included a fair ration of wine.

In no time at all, Marianne, speechless with horror, was stripped of her own clothes and dressed in the prison uniform, receiving a resounding slap on the buttocks from one of her impromptu tire-women in the process – a pleasantry which called down a severe rebuke on the head of its author.

'It was so tempting,' was the woman's excuse. 'Pity to lock up such a jolly little piece!'

Marianne's indignation was such that it almost robbed her of her voice but disdaining the two slatterns as unworthy of her notice, she turned her attention to the wardress.

'I wish to see the Mother Superior,' she announced. 'It is very urgent.'

'Our Mother Superior has let it be understood that she will see you today. Until then, you will wait quietly. For the present, go with the others to the chapel—'

Marianne had no choice but to leave the cell, stumbling in the clogs that were too big for her, and join the shuffling file of the other prisoners. About a score of women were moving in single file down the high, narrow corridor amid a great deal of coughing, sniffing and muttering and a strong smell of unwashed bodies. The general impression was of a herd rather than a file. The faces of all wore the same expression of dumb apathy. All their feet dragged on the uneven flagstones, all their shoulders were bowed. Only by their height and the hair, blonde, black, brown or grey escaping from the coarse linen caps, could the female prisoners of St Lazare be told apart.

Swallowing her impatience and resentment, Marianne took her place in the line but it was not long before she realized that the woman behind her was amusing herself by systematically treading on her heels. The first time it happened, she only turned round, thinking it was an accident. Coming after her was a dumpy little blonde person, her eyes hidden by pale, drooping lids that made her look half asleep. Her clothes were clean but the vacant grin on her slack lips made Marianne suddenly long to slap her face. The next time the rough wooden shoe scraped her ankle, she muttered under her breath: 'Watch what you're doing, you're hurting me—'

No answer. The other girl kept her eyes lowered, the same stupid smile on her pasty face. Then, for the third time, the sabot ground into Marianne's heel, so hard that she could not help giving out a sharp cry of pain.

Patience was not one of Marianne's chief virtues and the last few hours had used up what little she had left. She swung round instantly and dealt the offender a ringing blow on her plump cheek. This time, she found herself gazing into a pair of almost colourless eyes that reminded her oddly of an adder which her favourite horse, Sea Bird, had crushed beneath his hoof one day out hunting. The other girl said nothing, she simply bared her yellow teeth and hurled herself straight at her enemy's stomach. Immediately, all those round the two women stopped to watch, instinctively forming a circle to leave room for the two who were fighting. There were shouts of encouragement, all addressed to Marianne's opponent.

'Go it, la Tricoteuse! Hit her!'

'Thump her hard! Stuck-up little madam! An aristo!'

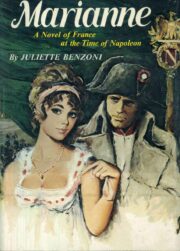

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.