Moved by her silent grief, the little man in the rusty black stood before her his arms mechanically cradling the sleeping child. But suddenly, Ellis straightened herself. She held out eager, trembling arms to the baby and taking her gently, laid her against her own flat chest, peering with a kind of terror into the tiny face crowned with a mist of brown curls. She touched the tight little fists with a timid, exploring finger. The tears dried and a look of gentleness came over her face.

The abbé's legs, trembling under the accumulated weariness of weeks, seemed to give way suddenly and he subsided into a chair and watched the last of the Seltons discovering the maternal instinct. There, in the firelight, the long face in its frame of red hair presented an indefinable picture of mingled love and pain.

'Who is she like?' Ellis asked softly. 'Anne was so fair and this child's hair is almost black.'

'She is like her father, but she will have her mother's eyes. You will see when she wakes—'

As if she had only been waiting for the words, Marianne opened a pair of eyes as green as young grass and looked at her aunt. But instantly, the tiny nose was screwed up, the tiny mouth was turned down woefully and the baby began to howl. Ellis started with surprise and almost dropped her. Her eyes flew to the abbé with an expression of near panic.

'Good God! What is it? Is she ill? Have I hurt her?'

Gauthier de Chazay smiled broadly, showing firm white teeth.

'I think she is merely hungry. She has had nothing but a little spring water since this morning.'

'And nor, I daresay, have you! What am I thinking of, sitting her with my grief while you and this little angel perish of hunger and fatigue—'

Within seconds, the silence in the house was a thing of the past. Servants came running. One was ordered to fetch a person named Mrs Jenkins, the others to produce upon the instant a hot supper, tea and brandy. Finally, Parry was commanded to make ready a room for the guest from France. Everything happened at astonishing speed. Parry disappeared, the servants brought a lavish repast and Mrs Jenkins made the solemn entry suited to her position as housekeeper, her ample person and considerable years. But this majesty melted like butter in the sun when Lady Selton placed the baby in her arms.

'Take her, my good Jenkins – she is all that remains to us of Lady Anne. Those bloodthirsty scoundrels have killed her for trying to save the unhappy queen. We must take care of her for we are all she has – and I have no one but her.'

When they were all gone she turned to the abbé de Chazay and he saw that tears were still running down her cheeks but she made an effort to smile and indicated the laden table.

'Sit down – eat, then you shall tell me all.'

The abbé talked for a long time, describing his flight from Paris with the baby after he had found her, alone and abandoned, in the d'Asselnat's town house after it had been looted by the mob.

Meanwhile, upstairs, Marianne, well washed and full of warm milk, was sleeping peacefully in a big room with hangings of blue velvet, watched over by the elderly Mrs Jenkins. The worthy housekeeper had dressed the fragile little body tenderly in lace and cambric that had once been her mother's and now, she was rocking her gently and lovingly and singing an old song conjured up from the recesses of her memory:

'Oh mistress mine! where are you roaming?

Oh mistress mine! where are you roaming?

O! stay and hear; your true love's coming,

That can sing both high and low…'

Whether Shakespeare's old song was addressed to the fleeting shade of Anne Selton or to the child come to find a refuge in the heart of the English countryside, there were tears in Mrs Jenkin's eyes as she smiled at the baby.

And so, Marianne d'Asselnat came to spend her childhood in the old home of her ancestors and grow up in old England…

Part I

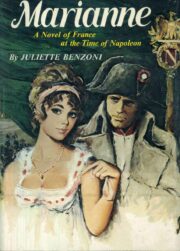

1809, THE BRIDE OF SELTON HALL

CHAPTER ONE

The Wedding Night

The priest's hand was raised in blessing and as he uttered the ritual words, all heads were bowed. Marianne realized that she was married. A wave of joy swept over her, almost savage in its intensity, and at the same time she had a sense of absolute irrevocability. From this moment she ceased to belong to herself and became, body and soul, one with the man who had been chosen for her. Yet, though the choice might not have been her own, not for anything in the world would she have wished him other than he was. From the first moment when he had bowed to her, Marianne had known that she loved him. And from then on she gave herself to him with a passionate devotion which she brought to everything she did, with all the ardour of first love.

Her hand, with the brand new ring, trembled a little in Francis's. She gazed up at him wonderingly.

'For ever,' she said softly. 'Until death do us part—'

He smiled, the kindly, rather condescending smile of an adult for an over-enthusiastic child, and pressed the slender fingers lightly before releasing them to hand Marianne to her seat. The mass was about to begin.

The new bride listened meekly to the first words but very soon her mind slipped away from the familiar ritual and returned, irresistibly, to Francis. Her eyes slid out from under the enveloping cloud of lace and fastened with satisfaction on her husband's clean-cut profile. Francis Cranmere, at thirty, was a magnificent human specimen. He was very tall and carried himself with a languid, aristocratic grace which, but for his muscular athletic frame, might have been thought feminine. Similarly, the stubborn brow and the powerful chin resting on the high muslin cravat, counteracted the rather too perfect beauty of features that, for all their nobility, seemed fixed in an expression of perpetual boredom. The white of the hands emerging from lace cuffs, would have done credit to a cardinal but the chest and shoulders moulded by the dark blue coat were those of a boxer.

Lord Cranmere was a man of contradictions, an angel's head on the body of an adventurer. But the whole had an undoubted charm to which few women were impervious. Certainly, for Marianne at seventeen he was pure perfection.

She closed her eyes for a second in order to savour her happiness, then opened them on the altar, decorated with autumn leaves and one or two late blooms amongst which a few candles burned. It had been erected in the great hall of Selton Hall because there was no catholic church for several miles around and even fewer priests. The England of King George III was going through one of its periodical violent bursts of anti-papist feeling and nothing less than the protection of the Prince of Wales had been required to enable this marriage between a catholic and a protestant to take place according to the rites of both churches. An hour before, the priest of the Church of England had blessed the couple and now the abbé Gauthier de Chazay was officiating by special favour. No power on earth could have kept him from blessing his goddaughter's marriage.

It was, moreover, a strange marriage, with no other pomp but these few flowers and candles, the one concession to the solemnity of the day. Around this makeshift altar, the familiar surroundings remained, as ever: the high white and gold ceiling with its hexagonal mouldings, the purple and white Genoa velvet hangings, the heavily gilded furniture and, last of all, the great canvases depicting the imposing figures of past Seltons. All this gave to the ceremony an impression of unreality and timelessness that was strengthened by the gown worn by the bride.

Marianne's mother had worn these things at Versailles, in the presence of King Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette on the day of her marriage to Pierre-Louis d'Asselnat, Marquis de Villefranche. There was a full gown of white satin oversewn with lace and rosebuds, worn over the wide cloth of silver underskirt swollen with panniers and a host of petticoats. The tight, constricting bodice with its square neck line was cut low, revealing a girlish bosom below the necklace made of many rows of pearls, while from the high powdered wig, frosted with diamonds, a great lace veil cascaded like the tail of a comet. This dress, with all its outmoded magnificence, Anne Selton had sent home as a keepsake to her sister Ellis who had treasured it ever since.

Many times, when Marianne was little, Aunt Ellis had shown her that dress. Each time, she had to hold back her tears as she drew it from its cedar wood chest but she loved to see the wonder on the child's face.

'One day,' she would tell her, 'you too will wear this dress. And that will be a happy day for you. Yes, by God, you shall be happy!' As she spoke she would thump her stick on the ground as though challenging fate to contradict her. And it was true, Marianne was happy.

But now, the thumping with which Ellis Selton had been in the habit of punctuating her commands echoed no longer, except in her niece's memory. For a week now, the generous, domineering old spinster had rested in the Palladian mausoleum across the park among her ancestors. This marriage had been her doing. It was her last wish and as such not to be denied.

Ever since that autumn evening when a weary man had deposited in her arms a baby only a few months old, crying with hunger, Ellis Selton had discovered a new meaning in her lonely life. Without effort, the ageing, arrogant spinster had transformed herself into a perfect mother for the orphan. Sometimes she would be overwhelmed by fierce waves of tenderness that woke her in the middle of the night, panting and sweating at the mere thought of the dangers through which the little girl had passed.

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.