'But, what is it all about? Has there been an attempt at assassination? Has a criminal escaped? Or are they looking for robbers?'

'Nothing like that, m'dame. It's all that bloody Savary, thinks he's the only one as knows how to serve the Emperor! So he goes on searching and nosing and asking questions. Who hatched it? Who laid it? Wants to know it all, he does.'

The farmer's confidences might have continued indefinitely but for the reappearance of the hairy gendarme, preceded this time by a sub-lieutenant, a dapper, beardless youth who approached the coach and bowed perfunctorily, taking in Marianne with an eye of insolent appreciation.

'You are Madame Sant'Anna, it appears.'

Outraged at the tone the young whipper-snapper had used to her, Marianne felt herself stiffen.

'I am the Princess Sant'Anna,' she said, very distinctly. 'It is usual to address me as Serene Highness, lieutenant. Apparently they do not teach you manners in the gendarmerie?'

'It is enough that we are taught to do our duty,' the young man said, in no way discomposed by her disdainful tone. 'My duty, Serene Highness, is to conduct you forthwith to the Minister of Police – if you will be good enough to ask your maid to make room for me.'

Before the outraged Marianne could say a word, the lieutenant had opened the door and climbed into the coach. Agathe rose automatically to relinquish to him her place beside Marianne, but her mistress laid a firm hand on her arm.

'Stay where you are, Agathe. I did not tell you to move and I am not in the habit of allowing any Tom, Dick or Harry to sit beside me. As for you, sir, I believe I must have misunderstood you. Will you repeat what it was you said?'

The lieutenant, obliged to maintain an uncomfortable stooping posture in the absence of anywhere to sit down, spoke in a voice of stifled anger.

'I said that I was to conduct you forthwith to the Minister of Police. Your name has been circulated to every guard post for more than a week. These are my orders.'

'Whose orders?'

'Whose orders would you expect? The Minister of Police, his grace the Duke of Rovigo, and therefore of the Emperor.'

'That remains to be seen,' Marianne retorted. 'Very well, if that is what you want, we will go to the Duke of Rovigo. I should not object to telling him what I think of him, and of his subordinates. Until then, however, I intend to remain mistress of my own coach. Have the goodness to take a seat next to my coachman, young man. And while you are about it, you may show him the way. Under no other circumstances will you get me to budge from this spot.'

'Very well. I will go.'

With a very bad grace, the young gendarme climbed out and went to join Gracchus, who welcomed him with a sardonic grin.

'Nice of you to come and bear me company, lieutenant. You'll find it's well enough up here. A little damp, maybe, but you get more fresh air than inside. Now, where is it we're going exactly?'

'Straight on, and none of your sauce my lad, or you'll be the worse for it. Drive on.'

For answer, Gracchus touched up his horses and began to bawl out a lusty, street urchin's version of the soldiers' march from Austerlitz:

'When we break through their line

Ta rum ta ra, ta rum ta ra,

When we break through their line

Then how we'll laugh…'

Laugh? Marianne, hunched up inside the coach, felt no desire to laugh but even so the infectious rhythm of the march and the warlike gaiety of the voice suited something in her mood. She was far too angry to be afraid, even for an instant, of this Savary or of his reasons for ordering her arrest at the very gates of Paris.

When, a little later, they arrived at the Hôtel de Juigné, Marianne saw that there had been changes here also. The place was clearly being redecorated. Everywhere there was scaffolding, buckets of plaster and paint pots left about by the workmen at the end of the day. In spite of this, and of the lateness of the hour (ten o'clock had not long sounded from Saint-Germain) the forecourt and antechambers were filled with footmen in glittering liveries and with visitors from every class of society. Instead of conducting Marianne upstairs to the dusty waiting-room on the first floor which led into the tiny, ill-furnished office that had belonged to the Duke of Otranto, the young lieutenant handed her over to a towering major-domo in red plush and powder. He flung open the doors into a salon on the ground floor furnished with an unswerving obedience to the known tastes of the Duke's imperial master. The room was filled with solid mahogany furniture and trophies made of ormolu, there were hangings of dark green with embroidered bees, a Pompeian chandelier and warlike allegorical scenes executed in stucco upon the walls. The final touch was given by an outsized bust of the Emperor, crowned with bays, sprouting from a marble plinth.

In the midst of all this, a lady in a gown of mauve taffetas, with a black pelisse and a rice-straw hat, was pacing up and down in an agitated manner. She was middle-aged, and her noble features and wide, thoughtful brow suggested a temper of mingled gentleness and austerity. It was a face that Marianne knew already from having seen it often in the house of Talleyrand: the Canoness de Chastenay, an aristocratic and intellectual lady who, it was said, had once entertained a certain partiality for the young General Bonaparte.

At Marianne's entry, she stopped her feverish pacing and regarded the newcomer in some surprise before uttering a joyful cry and hurrying to meet her with hands outstretched.

'Dear Muse of Song – oh, forgive me, dear Princess, I should say, what a joy and comfort to find you here!'

It was Marianne's turn to be surprised. How could Madame de Chastenay have known of the change that had occurred in her station. The Canoness gave a nervous little laugh and drew the younger woman over to a sofa guarded by a pair of forbidding bronze victories.

'But no one in Paris talks of anything else but your romantic marriage! That and the unfortunate Duke of Otranto's fall from grace are almost the only topics of conversation. Did you know that he is not to be governor of Rome after all? It seems the Emperor is perfectly furious with him on account of his making a bonfire of all the secret files and papers belonging to his ministry. He has been exiled, really exiled! It scarcely seems possible! But – where was I?'

'You were saying, madame, that people are talking about my marriage,' Marianne murmured, stunned by this flow of words.

'Ah, yes. Oh, it is quite extraordinary! You know, my dear, you are a real little slyboots! Hiding one of the greatest names in France like that! So romantic! Although, you must know, I was never really taken in. I guessed long ago that you were truly of noble birth and when we heard the truth —'

'But from whom did you hear it?' Marianne asked quietly.

The Canoness paused for a moment and appeared to reflect, then she was off again, more volubly than ever.

'How was it, now? Ah, yes – the Grand Duchess of Tuscany wrote to the Emperor about it as though it were something altogether remarkable! And so deeply moving! The beautiful young singer consenting to marry an unfortunate so dreadfully deformed that he could never bear to show himself in public! And, to crown it all, the great artiste then reveals that she is of noble race! My dear, I should think your story must be all over Europe by now.'

'But – the Emperor? What did the Emperor say?' Marianne persisted, feeling both bewildered and alarmed to discover so much talk about a marriage which she had believed secret. The court of Tuscany must be a hive of gossip indeed for the ripples of gossip started there to have spread so far and so fast.

'Goodness, I hardly know,' the Canoness answered. 'All I know is that his Majesty mentioned it to Monsieur de Talleyrand and roasted the poor Prince most unkindly for making the Marquis d'Asselnat's own daughter reader to the erstwhile Madame Grand.'

That was very like Napoleon. He must have been furiously angry at the marriage and had chosen to take out his wrath on Talleyrand. By way of changing the subject, Marianne asked: 'But what brings you here, madame, at this late hour?'

Instantly, Madame de Chastenay's sophisticated playfulness left her and she began to look as agitated as she had when Marianne had first entered.

'Oh, don't speak of it! I am still quite distracted! There I was in the Beauvaisis, with friends who have such an enchanting estate there and who – well, this very morning along comes a great lout of a gendarme to say that the Duke of Rovigo commands my presence instantly. And the worst of it is that I have not the least idea why, or what I could have done! I left my poor friends in the utmost anxiety and passed a terrible journey wondering all the time why I had been, not to put too fine a point on it, arrested. I was so wretched that I went first to call on Councillor Real to ask him what he thought and he urged me to come here without delay. Any delay, he said, could have the most serious consequences! Oh, my dear, I am in such a state – and I dare swear that you are just the same—'

No, not quite the same. Marianne forced herself to maintain an icy calm. She had her own reasons for thinking that the order concerning her came from a higher source, although she would never have believed that Napoleon would go so far as to have her arrested for daring to marry without his consent. However, there was no time to disclose her own fears to her companion. The majestic usher reappeared to inform Madame de Chastenay that the minister was ready to receive her.

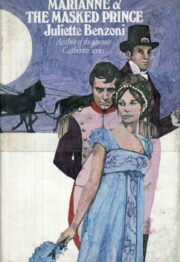

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.