Once the cardinal had begun on this subject it was impossible to stem the flow, much less to bring him back to one which, like Dona Lavinia, he clearly preferred to avoid. This flood of eloquence was intended to prevent Marianne from getting a word in and at the same time give her thoughts another direction. In this it was to some extent successful for as soon as the two of them entered the vast stable yard, Marianne temporarily forgot the mysterious Lucinda in abandonment to her lifelong passion for horses. She found, too, that her coachman, Gracchus-Hannibal Pioche, was there before her, apparently as happy as a pig in clover. Although he spoke no Italian, he had succeeded in making himself perfectly understood with his Parisian street urchin's capacity for mime. He was already friends with all the grooms and stable lads who instantly recognized a fellow worshipper at the shrine of the horse.

'This place is heaven, Mademoiselle Marianne!' he exclaimed joyfully as soon as he set eyes on her. 'I never saw finer animals!'

'Well, if you want to be allowed in here much longer, young man,' the cardinal observed, half-angry, half-amused, 'you will have to learn to say your highness – or even your serene highness, if you prefer.'

Gracchus blushed violently and stammered: 'Ser – you'll have to be patient with me, mad – I mean your highness. I'm not sure I'll find it easy to get it right first off.'

'Just call me madame, Gracchus, and that will do very well. Now, show me the horses.'

They were in truth magnificent, full of fire and blood, with powerful shoulders and strong, slender legs. Nearly all of them had pure white coats. A few were pitch black, but no less beautiful. Marianne had no need to feign admiration. She had an excellent eye for the points of a horse and within an hour had succeeded in convincing all the inhabitants of the stables that the new Princess was altogether worthy of the family. Her beauty did the rest and by the time she returned to the villa, late in the afternoon, Marianne left behind her one small world irrevocably won, much to the cardinal's satisfaction.

'Do you realize what you are going to mean to them? A real, live mistress, someone visible who can understand them. Your coming is a real relief to them.'

'I am glad of it, although they will have to continue to do without me for a great part of the time. You know that I must go back to Paris – if only to explain my new position to the Emperor. You do not know him in his rages.'

'I can imagine it. But you are under no compulsion to go. If you were to remain here...'

'He would be quite capable of sending an armed guard to fetch me, just as he escorted you – or your double – to Rheims. No, I thank you. I have always preferred to stand and fight and this time I mean to explain myself in person.'

'What you mean is that you would not for the world lose this opportunity of seeing him again.' The cardinal sighed. 'You are still in love with him.'

'Have I ever denied it?' Marianne retorted proudly. 'I do not think I ever pretended otherwise. Yes, I do love him still. I may regret it as much as you, although for different reasons, but I love him and that is all there is to it.'

'I know. We need not quarrel about that again. There are times when you put me very much in mind of your Aunt Ellis. The same impatience and the same relish for a fight! And the same generosity. Never mind. I know you will come back here, and that is what matters.'

The sun was going down behind the trees in the park and Marianne watched its descent with a sense of foreboding. The coming of twilight wrapped the domain in an indefinable sadness, as if life as well as light were being withdrawn.

Marianne shivered suddenly as they made their way back to the house and hugged the muslin shawl that went with her simple white dress more closely about her shoulders. Walking slowly beside the cardinal, she stared up at the white mass of the house as it loomed up before them. They were approaching it now from the right, the side where Prince Corrado had his apartments. The tall windows were dark. Possibly the curtains were already drawn but if so no chink of light showed through.

'Do you think,' she said suddenly, 'that I ought to thank the Prince for the jewels he sent me this morning? Surely it would be the merest politeness?'

'No. It would be a mistake. As far as Corrado is concerned, they are rightfully yours. You are their keeper, in much the same way as the French king was keeper of the crown jewels. One does not return thanks for such a charge.'

'But the emeralds —'

'Are doubtless a personal gift – to the Princess Sant'Anna. You will wear them, display them – and hand them on to your descendants. No, it is useless to try and approach him. I am sure he does not wish for it. If you would please him, wear the jewels he has given you. That will be the best way to show him your pleasure.'

For dinner that night, which she took sitting opposite the cardinal in the vast dining-room, Marianne clasped a large, antique brooch of pearls and rubies in a gold setting to the low-cut bosom of her high-waisted dress. Heavy, matching ear-rings hung from her ears. But although she kept glancing discreetly at the ceiling throughout the meal she saw no sign of movement and no eyes watching her, and she was surprised to note a small pang of disappointment. She knew that she was looking beautiful and she would have liked her beauty to be a silent tribute to her unseen husband, a kind of thank you. But she saw no one, not even Matteo Damiani on whom she had not set eyes all that day. When she met Dona Lavinia later, on her return to her own room, a question sprang naturally to her lips.

'Has the Prince gone away?'

'Why, no, your highness. Why should you think so?'

'I have seen no sign of his presence all day, not even his secretary or Father Amundi.'

'Matteo has been seeing some tenants at some distance and the chaplain has been with his highness. He rarely leaves his own apartments, unless for the chapel or the library. Do you desire me to inform Matteo that you wish to see him?'

'By no means,' Marianne said, rather too quickly. 'I was merely asking.'

That night in bed she found it hard to sleep and lay for several hours unable to close her eyes. Round about midnight, just as she was beginning at last to fall into a doze, she heard the sound of a horse galloping across the park and roused for a moment to listen. Then, reflecting that it was most probably Matteo Damiani returning home, she relaxed and, closing her eyes, fell into a deep sleep.

The next few days passed quietly, in much the same way as the first. Marianne explored the estate, accompanied by the cardinal, and drove out several times to see the surrounding countryside in one of the many carriages which belonged to the villa. She paid a visit to the baths of Lucca, and also to the gardens of the Grand Duchess Elisa's sumptuous villa at Marlia. The cardinal, dressed in plain black, attracted little attention but Marianne's beauty aroused admiration and a good deal of curiosity, for the news of the marriage had spread fast. People in the villages and country lanes came out to catch a glimpse of her, bowing deeply as she passed and regarding her with an admiration touched with compassion that drew a smile from Gauthier de Chazay.

'Do you know, they look on you practically as a saint?'

'Me? A saint? How absurd!'

'The general belief in these parts is that Corrado Sant'Anna is a desperately sick man. They are impressed that you, who are so young and beautiful, should give yourself to one so afflicted. When the birth of the child is announced you will be hailed almost as a martyr.'

'How can you make a joke of it!' Marianne was shocked by the prelate's lightly cynical tone.

'My dear child, if one is to get through life without being too much hurt, the best way is to look for the funny side of things. Besides, it was necessary for you to know the reason why they regard you in this way. Now it is done.'

Most of Marianne's time, however, was spent in the stables, in spite of the cardinal's remonstrances. He did not consider the stables a proper place for a great lady, besides which it alarmed him that in her condition she should spend long hours in the saddle, mounting each animal in turn in order to discover at first hand its merits and defects. Marianne laughed at his fears. She was in the best of health. No sickness troubled her, and the open air life suited her to perfection. Rinaldo, the head groom, followed her everywhere, like a large dog, as with the skirts of her habit flung over her arm (she had not dared to adopt the masculine dress which she preferred for riding for fear of causing a scandal), she tramped for miles over the fields where the horses were pastured.

On her return from these exhausting treks she would eat a hearty dinner and then tumble into bed to sleep like a child until sunrise. Even the curious sadness which descended on the villa each night with the gathering darkness no longer affected her. The Prince had made no further sign, except for a message to express his delight at her interest in his horses, and Matteo Damiani appeared to be keeping his distance. On those occasions when he chanced to meet Marianne, he merely bowed deeply, inquired after her health and then effaced himself.

The week slipped by, swiftly and without incident, and so pleasantly that she was hardly aware of it until it dawned on her at last that she was not particularly anxious to return to Paris. The deadly weariness of the journey, the unbearable nervous tension, her agonies and fears had all vanished.

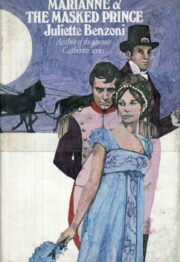

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.