The door of the red salon opened to admit the cardinal once more, but this time he was not alone. Three men were with him. One was a little, dark fellow with a face that seemed entirely made up of nose and whiskers. The cut of his coat and the big, leather folder which he carried under his arm proclaimed the notary. The other two might have stepped straight down from a gallery of ancestral portraits: two venerable gentlemen in velvet suits dating from the time of Louis XV, and bob wigs. One leaned on a stick, the other on the cardinal's arm and both their faces were expressive of extreme old age.

They bowed with an exquisite, old-fashioned courtesy to Marianne who curtsied deeply in return. They were presented to her as the Marquis del Carreto and Count Gherardesca, kinsmen of the Prince, and they were there to witness the marriage. The last-named, the one who walked with a stick, was also, in his capacity as the Grand Duchess's chamberlain, to register the marriage officially.

The lawyer seated himself at a small table and opened his brief-case. Everyone else sat down. At the far end of the room were Dona Lavinia and Matteo Damiani, who had come in after the witnesses.

Marianne was so nervous and distraught that she hardly listened to the long, pedantic reading of the marriage contract. The endless convolutions of legal terminology were irritating. All she wanted now was to get it over, quickly. She was not in the least interested in the enumeration of the possessions which Prince Sant'Anna was to settle on his wife, any more than in the truly royal sum of her allowance. Her attention was divided between the silent mirror facing her, behind which the Prince might once more be watching, and the unpleasant sensation that she herself was the focus of an insistent gaze.

She could feel that gaze between her bare shoulders and on the back of her neck where her hair was piled up into a heavy chignon to support the diadem. It slid over her skin, dwelling on the soft curve of her neck with an almost magnetic force, as if someone were trying, by sheer force of will, to attract her attention. At last, her overwrought nerves could bear it no longer. She turned quickly but met nothing but Matteo's frozen stare. He seemed so indifferent that she thought she must have been mistaken but no sooner had she turned back than the sensation was renewed, more distinctly than ever.

Her discomfort increased until she welcomed with relief the end of this obligatory ceremony. She signed, without so much as glancing at it, the act of settlement which the lawyer presented to her with a low bow, then her eyes went to her godfather's and he smiled at her.

'Now we can go to the chapel,' he said. 'Father Amundi is already waiting for us there.'

Marianne had expected the chapel to be situated somewhere in the building but she realized that she was mistaken when she saw Dona Lavinia coming towards her with a long, black velvet cloak which she placed on her shoulders, taking care to put up the hood.

'The chapel is in the park,' she explained. 'The night is warm but it is chilly under the trees.'

As he had done when leading her from her room, the cardinal took his god-daughter's hand and led her solemnly to the great marble steps where footmen armed with torches awaited them. The remainder of the little procession formed up behind them. Marianne saw that Matteo Damiani had offered his arm to the aged Marquis del Carreto, next came Count Gherardesca with Dona Lavinia, who had thrown a black lace shawl hastily over her head and shoulders. The lawyer and his brief-case had vanished.

In this way they descended into the park. As they emerged, Marianne saw Gracchus and Agathe waiting in the loggia. They were staring at the approaching procession with such flAbbérgasted expressions that Marianne suddenly wanted to laugh. They had clearly not yet taken in the incredible news which their mistress had imparted to them before she dressed, that she was here in order to marry an unknown prince, and if they were too well-mannered to make any comment, the dismay on their honest faces gave a good idea of their thoughts. Marianne smiled at them as she passed and indicated that they were to follow after Dona Lavinia.

'They must think I am mad,' she thought. 'Agathe does not matter. She is a nice girl but she has no more brain than a linnet. But Gracchus is a different matter. I shall have to speak to him. He has a right to know a little more.'

The night was black as ink. The sky was starless and invisible but a slight wind blew the torches carried by the lackeys. A low, distant rumbling presaged a storm but the cortege advanced at a slow, solemn pace which set Marianne's teeth on edge. She muttered under her breath. 'This is more like a funeral procession than a marriage! There ought to be a friar chanting the Dies Irae!'

The cardinal's hand tightened on hers until it hurt.

'A little more conduct!' he chided softly, without looking at her. 'It is not for us to impose our wishes here. We must obey the Prince's orders.'

'They indicate his joy at this marriage!'

'Do not be bitter. And above all, do not be stupid and cruel. No one could desire the joy of a true wedding more than Corrado. For you, this is no more than a formality – for him it is a source of bitter regrets.'

Marianne accepted the reproof without protest, aware that she had deserved it. She gave a sad little smile and asked in a different tone: 'All the same, there is one thing I should like to know.'

'And that is?'

'My – Prince Corrado's age.'

'Twenty-eight, or a little more, I believe.'

'What? Is he so young?'

'I thought I told you he was not old.'

'Yes, but – so young!'

She forbore to add that she had pictured a man in his forties. To one like Gauthier Chazay on the brink of old age, forty was the prime of life. But now she discovered that the unfortunate whose name she was to bear, whom a cruel fate had condemned to perpetual seclusion was, like herself, young, with all the same youthful aspirations towards life, and happiness and freedom. The recollection of that muffled voice, with its weight of sadness, filled her with an immense pity, joined to a real desire to help him, to lighten as far as might be possible the sufferings she could imagine.

'Godfather,' she whispered. 'I would like to help him – give him, perhaps, a little affection. Why does he so stubbornly refuse to let me see him?'

'You must leave it to time, Marianne. In time Corrado may perhaps come to think differently – although I do not expect it. Remember only, if it will make it easier for you, that you are bringing him the thing he has always dreamed of: a child to bear his name.'

'Even though he will not be its real father! He asked me – to bring him here from time to time. I will do it gladly.'

'But – were you not listening to the marriage contract? You have pledged yourself to bring the child here once a year.'

'I – no, I did not hear,' she confessed, a slow flush spreading over her face. 'I must have been thinking of something else.'

'It was hardly the time,' the cardinal said gruffly. 'You signed, at all events —'

'And I will keep my word. After what you have told me I shall even be glad to do it. Poor – poor Prince! I would like to be a friend to him, a sister. Indeed I should!'

'God grant that you may,' the cardinal sighed. 'But I do not hope for it.'

The avenue that led to the chapel lay behind the right wing of the house, a little way beyond the gateway leading to the stables. As she rounded the corner of her new home, Marianne saw that the mirror-like sheets of water surrounded it on all four sides, but that stretching almost the whole length of the rear of the building was an elaborate grotto, built around the entrance to a cavern.

Bronze lanterns attached to every pillar illuminated the whole of this remarkable edifice and were reflected in long, gold streamers in the water, giving to the whole the air of a Venetian carnival. Then the way leading to the chapel passed under the shade of a small grove of trees and the elegant grotto was lost to sight. Soon, even the lights of the villa disappeared, showing no more than an occasional glimmer between the leaves.

The chapel itself, raised up in a small clearing, was a low, dumpy building of considerable age. In style, it was a very early romanesque, expressed in massive walls, pierced by few apertures, and rounded arches. Its primitive solidity contrasted with the somewhat artificial elegance of the palace and its encircling waters, like some obstinate, cross-grained elderly relative, sternly disapproving the follies of youth.

The small, arched doorway was open, allowing a glimpse of lighted candles within, an ancient altar stone covered with an immaculate white cloth and the golden cope of the old priest waiting there. There was also a curious, black shape which Marianne was unable to make out clearly from outside. It was only when she stood actually on the threshold of the church that she saw what it was. Black velvet curtains had been hung from the low vaulted roof, cutting off half of the choir, and she realized that the brief hope which she had cherished of being allowed at least a glimpse of the Prince's figure during the ceremony had failed. He was, or would be, concealed within that velvet alcove, next to which were a chair and a prie-dieu, the pair, no doubt, to others placed behind the curtains.

'Even here —' she began. The cardinal nodded.

'Even here. Only the priest will be able to see both parties, for the curtains are open on the altar side. It is necessary that he should be able to see both husband and wife as they make their vows.'

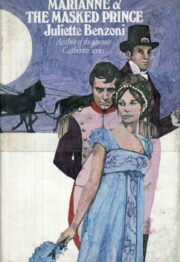

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.