It was another who had taught her love and every fibre of her body trembled even now with intoxicating gratitude at the memory of those white-hot nights at Butard and the Trianon. Yet it was this love also which had given birth to the woman whose image she had contemplated only a moment past in those ridiculous mirrors: a statue of almost Byzantine majesty and splendour, huge eyes in a set, pale face, Her Serene Highness the Princess Sant'Anna. Serene… most serene… ineffably serene, while her heart was wrung with grief and anguish. What a mockery!

Tonight there was no question of love, only of a marriage, positive, realistic, implacable. A union of two people in trouble, Gauthier de Chazay had called it. Tonight no man would come knocking at the door of this room, no desire would come to claim her body in which life, secret as yet but already all-powerful, was growing… no Jason would appear to demand payment of a debt, fantastic yet disturbing…

Marianne leaned on the bronze window hasp, fighting off the giddiness which overwhelmed her, thrusting back the mariner's image as she suddenly thought that if he had come she might have felt a real happiness. But he was not there and the world was strangely empty. She wanted to cry out, and she pressed her be-ringed fingers into her mouth to keep back that absurd call for help. Decked in jewels an empress might have envied, she had never felt more miserable.

She was shaken out of her morbid state when the double doors of her room were flung wide open and the shadows were dispelled by the appearance of six footmen holding branched candlesticks aloft. Aureoled in the sparkling light of the dancing flames, his robes of red watered silk sweeping the polished floor, the cardinal entered in all the splendour of the Church of Rome and at the glory of his entrance Marianne blinked like a night bird brought suddenly into the light. The cardinal's gaze rested thoughtfully on her for a moment but he made no comment.

'Come,' he said, merely. 'It is time.'

Whether it was his words or the blood red of his garments, Marianne could not have said, but she felt like one condemned, being summoned to the scaffold. She went to him, none the less, and laid her bejewelled hand on the red gloved fingers he held out to her. Their two trains, the sweeping capa magna and the queenly gown, whispered in concert over the marble surface of the rooms.

As they walked through them, Marianne saw with amazement that every room was lighted as if for a ball, yet nothing could have been less festive than this huge, magnificent emptiness. She thought, for the first time in years, of the fairy stories she had loved as a child. Tonight, she was Cinderella, Donkeyskin and the Sleeping Beauty all rolled into one, but for her there was no Prince Charming. Her prince was a phantom, invisible.

In this way, in slow and solemn procession, they traversed the entire palace. It was as though the cardinal were proudly presenting the newcomer to the assembled shades of all those who had once lived, loved and, perhaps, suffered in this place. At last, they came to a small saloon, hung with red damask, in which the principal article of furniture was a tall mirror of the French regency period, set on a gilt console and framed by a pair of bronze girandoles bearing clusters of lighted candles.

Bidding Marianne with a gesture to be seated, the cardinal stood beside her in silence with the air of one waiting for something. His eyes were on the mirror, which Marianne was sitting facing, but he had retained her hand in his, as if for reassurance. Marianne felt more oppressed than ever and she was already opening her mouth to ask a question when he spoke.

'My friend, here, as I promised, is Marianne d'Asselnat de Villeneuve, my god-daughter,' he said proudly.

Marianne shivered. It was to the mirror he had spoken, and now it was the mirror that answered.

'Forgive my silence, my dear cardinal. I should have spoken first, to welcome you, but I must confess that I was dumb with admiration. Madame, your godfather endeavoured to describe your beauty to me but, for the first time in his life, his eloquence has proved unequal to the task; so far unequal that only the fact that none but a poet could find words to express such divinity can excuse him. Let me say how deeply – humbly grateful I am to you for being here – and for being yourself.'

The voice was low and muffled. Its very tonelessness gave it a note of weariness and profound sadness. Marianne tensed, to control the excitement which was quickening her breath. She too looked at the mirror from where the voice seemed to come.

'Can you see me?' she asked softly.

'As clearly as if there were no obstacle between us. Let us say, I am the mirror in which you see yourself reflected. Have you ever seen a mirror happy?'

'I wish I could be sure of that – your voice is so sad.'

'That is because it is little used. A voice that has nothing to say comes to forget that it could sing. In the end, it is crushed by silence. But your voice is pure music.'

It was strange, talking to someone who remained invisible, but little by little Marianne acquired confidence. She decided it was time she took her own fate in hand. The voice was that of one who had known suffering, or was suffering still. She determined to play this game for herself. She turned to the cardinal.

'Godfather, would you leave me for a moment? I should like to talk to the Prince, and I should find it easier alone.'

'It is natural. I will wait in the library.'

No sooner had the door closed behind him than Marianne rose but instead of moving closer to the mirror she turned away towards one of the windows. It unnerved her to sit face to face with herself, hearing the bodiless voice speaking, as it was speaking now, with a shade of hesitation.

'Why did you send the cardinal away?'

'Because I must speak to you. There are some things, which must, I think, be said.'

'What things? I understood that my eminent friend had explained the precise nature of our agreement?'

'And so he has. It is all perfectly cut and dried; at least, I think so.'

'He told you that I shall not interfere in your life? The only thing he may not have said – but which I will ask…'

He paused and Marianne was aware of a slight break in his voice, but he recovered himself almost at once and continued: 'I will ask you, when the child is born, to bring him here sometimes. I should like him to learn to love this land, in my place, to love this house and its people, for whom he will be a real person – not a furtive shadow.' Again there was the slight, almost imperceptible break and Marianne felt her heart swell suddenly with a rush of pity. At the same time, another part of her mind was saying that all this was absurd, fantastic, and most of all this desperate veil of secrecy in which he wrapped himself. Her voice, when she spoke, was imploring.

'Prince – pardon me, I beseech you, if my words give you pain, but I do not understand and I want to so much. Why all this mystery? Why may I not see you? Surely I have the right to know my husband's face?'

There was a silence, so long and heavy that for a moment she was afraid that she had driven her strange interlocutor away. She was afraid that her impulsiveness had made her go too far, and too soon. But at last the answer came, slow and final as a judgement.

'No. That cannot be. In a little while, we shall be together in the chapel and my hand will touch yours – but we shall never be as close again.'

'But why, why?' she persisted. 'My birth is as good as your own and I fear nothing – however terrible – if that is what restrains you.'

There was a brief, low, mirthless laugh.

'You have been here so short a time and already you have heard men talk, have you not? I know – they have all sorts of theories about me, of which the most agreeable is that I am the victim of a hideous disease, leprosy or something of that kind. I am not a leper, madame, or anything of the kind. Nevertheless, it is impossible for us to meet face to face.'

'But in the name of God, why?'

This time it was her voice that broke.

'Because I would not risk becoming an object of horror to you.'

The voice was silent, and this time the mirror did not speak for so long that Marianne realized she was truly alone. Her hands, which had been gripping the thick, shiny leaves of some unknown plant in a Chinese vase, relaxed and she let out her breath in one long sigh. The disturbing presence had gone, to Marianne's great relief, for now she thought she knew what she was dealing with. The man must be a monster, some wretched semblance of humanity, doomed to darkness by repulsive disfigurement, too hideous to be endured by any eyes but those which had known him from birth. That would explain Matteo Damiani's stony countenance, the pain in Dona Lavinia's and perhaps also the childishness of Father Amundi's old features. It would explain, too, why he had broken off their interview when so many things were still to be said.

'I was clumsy,' Marianne reproached herself. 'I was in too much of a hurry. I should have approached the subject more cautiously, not rushed in at once with the question I wished to ask. I should have tried to penetrate the mystery little by little, by careful hints. And now I daresay I have frightened him.'

One other thing which surprised her was that the Prince had asked her nothing about herself, her life, her tastes. He had merely praised her beauty, as if that were the only thing that mattered in his eyes. Marianne reflected a little bitterly that he could scarcely have shown less curiosity if she had been a handsome filly destined for his precious stables. Indeed, it was more than likely that Corrado Sant'Anna would have made inquiries into the health and habits of such an animal. But, after all, for a man whose sole object in life was the possession of an heir to carry on his ancient name, the physical characteristics of the mother were bound to be of paramount importance. Why should Prince Sant'Anna concern himself with the affections, feelings and habits of Marianne d'Asselnat?

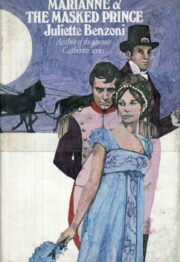

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.