'The service is almost over,' he whispered. 'When they have all gone, we can talk.'

They did not have long to wait. In a few moments the priest left the altar, carrying the censer. The church emptied slowly. There was a sound of chairs scraping, then footsteps moving away. The verger came to extinguish the candles and the lamp. The only lights left burning were those standing before a fine statue of John the Baptist in the transept, the work of the same artist as the tomb. The cardinal rose and seated himself, with a gesture to Marianne to do the same. She was the first to speak.

'I have come, as you commanded…'

'No, not commanded,' Gauthier de Chazay corrected her mildly. 'I merely asked because I thought it best for you. You have come – alone?'

'Alone. As you knew I should, did you not?' There was an almost imperceptible shade of bitterness in her voice which did not escape the priest's subtle ear.

'No, God is my witness that I should have preferred to see you find a man in whom your duty and your inclination could combine. But I realize that you had little time, or choice, perhaps. And yet, it seems to me that you feel some resentment towards me for the situation in which you find yourself.'

'I blame no one but myself, godfather, be sure of that. Only tell me, is everything arranged? My marriage…'

'To the Englishman? Has been duly annulled, of course, or you would not be here. It was not difficult. The circumstances were exceptional and since the Holy Father's position was also somewhat unusual we were obliged to make do with a small court to decide your case. I had counted on that to enable us to proceed so rapidly. I have, moreover, sent word of these proceedings to the consistory of the Church of England and written to the lawyer responsible for marriage settlements. You are quite free.'

'But for so short a time! But thank you. I can never be sufficiently grateful to you for releasing me from a bondage that was hateful to me. You seem to me, godfather, to have become a remarkably powerful person.'

'I have no power but what comes to me from God, Marianne. Are you now ready to hear the rest?'

'I think I am.'

How strange it was, this conversation in the empty cathedral. They were alone, sitting side by side, gazing into a dark world in which, from time to time, a candle flame would spurt up to reveal a masterpiece. Why here, rather than the inn where the cardinal could have entered in disguise as easily as the Abbé Bichette had done, in spite of the soldiers? Marianne knew her godfather well enough to be sure that he had chosen his ground deliberately, perhaps in order to add to the solemnity of what he had to say. It may have been for the same reason that he seemed to pause now before going on. His eyes were closed and his head bent. Marianne guessed that he was praying but her nerves had been strained to breaking point by the journey and her mental anguish. She could not control the impatience in her voice as she muttered: 'I am listening.'

The cardinal rose and laid his hand on the girl's shoulder. 'You are on edge, my child,' he said, with gentle reproach, 'and it is no wonder, but you see the responsibility for what is to come will be mine and it is only natural that I should feel the need for a moment's reflection. Listen, then, but remember, above all, that you must never despise the man who is about to give you his name. You will be joined in marriage but your union will never be complete and it is this which troubles me, for it is not thus that a man of God should contemplate a marriage. Yet each of you has something to give the other. He will save you and your child from dishonour and you will give him a happiness for which he had ceased to hope. Thanks to you, the great name which he had doomed to die with him will yet survive.'

'Can this man not have children? Is he too old?'

'He is neither old nor impotent but for him the idea of having children is unthinkable, fraught with terror even. It is true that he could have adopted a child but he recoils in horror at the thought of grafting a common shoot on to his ancient stock. You bring him the best blood of France and mingled with it the blood, not merely of an emperor, but of the one man he admires most in all the world. Tomorrow, Marianne, you are to be married to Prince Corrado Sant'Anna —'

Forgetting her surroundings, Marianne uttered a faint cry. The man whom no one has ever seen?'

The cardinal's face was stony. His blue eyes flashed.

'What do you know of him? From whom have you heard this?'

Briefly, Marianne described the scene which she had witnessed at the inn. At the end, she added: 'They say he suffers from some terrible disease and that is why he hides himself away, they say even that he is mad —'

'People will talk and if they do not talk, still they will think. No, he is not mad. As for why he chooses to live in seclusion, that is not for me to divulge. It is his secret. He may reveal it to you one day, if he sees fit – although I should be surprised. All you need to know is that his motives are not merely honourable but very noble.'

'But – surely I must see him – if we are to be married?' Unconsciously, Marianne spoke hopefully.

The cardinal shook his head. 'There is no curbing feminine curiosity. Listen to me, Marianne, for I shall not say this again. Between you and Corrado is a new pact, like the one you and I have made together. He will give you his name and acknowledge your child, who will one day inherit all his titles and possessions, but it is unlikely that you will ever look upon his face, even during the wedding ceremony.'

'But you know him?' Marianne cried, galled by this mystery to which the cardinal appeared to be a party. 'You have seen him? Why does he hide himself like this? Is he a monster?'

'Certainly I have seen him, many times. I have known him ever since the dreadful day of his birth. But I have sworn on my honour and on the Gospels never to speak of his person. Yet God knows, I would give much to make it possible for your marriage to be a real one in the sight of all, for I have met few men of such worth. But as things are, I believe that in bringing about this marriage I am acting in the best interests of both of you, by joining together, as it were, two people in trouble. As for you, you must repay him for what he gives to you, for in future you will be a very great lady, by conducting yourself honourably, with due respect for the ancient family to which you will belong. Its roots go back as far as classical times and she who lies in this tomb was not unconnected with it. Are you prepared for this? For make no mistake, if you have come seeking nothing but a cover that will allow you to live as you please with any man, you had better go away and look elsewhere. Never forget that what I am offering you is not happiness but the honour and dignity of a man who will not be beside you to defend them, that and a life free from all material cares. In short, I expect you to behave as befits your birth and breeding. If these conditions seem too hard to you, you may still draw back. I will give you ten minutes to think whether you will remain the singer Maria Stella or become the Princess Sant'Anna.'

He made a move as if to leave her alone to her thoughts but Marianne, seized with a sudden panic, gripped his arm.

'One thing more, godfather, I beg of you. I must make you understand what this decision means to me. I know it is not for the daughter of a great house to raise objections to the match made for her by her family, but you must admit the circumstances are unusual.'

'I do admit it. Yet I thought you had done with objections.'

'It is not that. I do not object. I trust you and I love you as I should my own father. All I ask is that you explain a little more. You tell me that I must live henceforth as befits a Sant'Anna, respect the name I bear?'

The cardinal's voice hardened. 'I did not think to hear such a question from your lips.'

'I do not know how to say it,' Marianne said desperately. 'What I mean is: what will be my life when I have married the Prince? Shall I be obliged to live in his house, under his roof —?'

'I have already told you, no. You may live precisely where you choose, in your own house, at the Hôtel d'Asselnat or where you will. You may also reside whenever you wish to in any of the houses belonging to the Sant'Annas, either in the villa you will see tomorrow or in any of their palaces, in Venice or in Florence. You will be perfectly free and Sant'Anna's steward will ensure that your life is not merely free from practical cares but as magnificent as befits your station. I only mean that you should live up to that station. No scandals, no passing fancies, no —'

'Oh, godfather!' Marianne cried, hurt. 'What right have I ever given you to think that I could sink so low —'

'Forgive me. I too am expressing myself badly. That was not what I meant to say. I was still thinking of your chosen profession. You may not have been aware of its dangers. I know you have a lover, and who he is. I may deplore the choice of your heart, but I know that he can call you back to him whenever he will. You cannot fight both him and yourself. All I ask, my child, is that you should remember the name you bear and be discreet. Never do anything that may give your child – now the child of both of you – any cause to reproach you. Indeed, I believe that I may trust you. You are still my own dear child. Only you have been unlucky. Now I will leave you to think.'

The cardinal moved away quietly to kneel before the statue of St John, leaving Marianne alone by the tomb. She turned to it instinctively, as if those stone lips could give the answer for which the cardinal was waiting. Dignity, that must have been the story of the girl who lay there. She had lived and died in dignity, and in what grace she clothed it! Marianne had to confess, moreover, that she did not honestly care for adventures, not at least for those she had encountered, and she could not help thinking that if things, and especially Francis, had been different, she would at that very moment have been living a life of peace and dignity amid the grandeurs of Selton Hall.

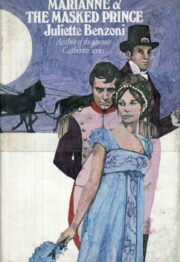

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.