Marianne dropped a light kiss on her friend's cheek. 'Poor Arcadius. You do not deserve that. I am sorry I raked up all these memories you were trying so hard to forget. Only tell me, how long will it take me to reach Lucca?'

'It is about six hundred miles,' Arcadius replied, with a speed that showed how glad he was to talk of something else. 'The road takes you by Mont Cenis and Turin. We should be able to cross the pass at this time of the year, with luck, and with good post horses, should cover between twenty-five and thirty leagues a day.'

'That is if we make halts every night,' Marianne said. What if we sleep in the coach and simply stop to change horses?'

'I should not advise it, especially for a woman. And you would need at least two coachmen. Gracchus could never do it alone. You must reckon on fifteen days at the best, Marianne. You cannot travel so fast in the mountains.'

'Fifteen days! That will mean leaving on the first of May! It does not leave much time for Jason to come. Suppose – suppose one were to travel on horseback?'

This time Jolival laughed outright.

'It would be much slower. You could not keep up a pace of sixty miles a day for very long. You would need to be in training, with a hide like a cavalryman's to stand such a journey. Have you heard the story of the courier of Friedland?'

Marianne shook her head. She loved Arcadius's stories.

'Of all the Emperor's couriers,' Jolival began, 'there was one who was especially swift, and he was the rider named Esprit Chazal, known as Moustache. On the day after the battle of Friedland, Napoleon wanted to send the news to Paris as fast as possible. To begin with, he decided to entrust it to his brother-in-law,

Prince Borghese, one of the best horsemen in the Empire, but twenty-four hours later he sent his famous Moustache off with the same news. After fifty leagues, Borghese changed his horse for a travelling coach and travelled day and night. Moustache, for his part, made do with what he had: post horses and his own endurance. He rode day and night and in nine days, would you believe it, he had covered the four hundred and fifty leagues between Fried-land and Paris – and arrived before Borghese. A remarkable exploit! But it nearly killed him and Moustache is a giant, carved in granite. You are no Moustache, Marianne my dear, even if you have far greater courage and endurance than most women. I will procure as stout a carriage as I can and we will travel —'

'No,' Marianne said swiftly. 'I want you to stay here.'

Arcadius gave a start and his brows drew together.

'Here? Why? On account of this promise made to your godfather? Are you afraid that —?'

'Not in the least, but I want you to stay and wait for Jason as long as possible. He may come after I have left, and if there is no one here to meet him he cannot try to come after me. He is very strong, a sailor and I have no doubt an excellent horseman. It may be' – she hesitated and now it was her turn to blush – 'for my sake, he may try and emulate Moustache's exploit.'

'And ride from Paris to Lucca inside a week? I believe that he might do it, for you. Well, I will stay – but you cannot set out alone – the long journey —'

'I have travelled on long journeys alone before, Arcadius. I shall take my woman, Agathe, and with Gracchus-Hannibal on the box, I shall have little to fear.'

'Would you like me to find Adelaide?'

Marianne hesitated. 'I have heard nothing from her,' she began.

'I have. I have been to see her several times. It is true that she shows no disposition to return. Without wishing to offend you, I really think that she is mad. I'll swear she is in love with that fellow Bobèche!'

'Well leave her then. I can do quite well without her. I did think of taking Fortunée but she could never resist talking. As far as the world is concerned, I am going to Lucca to take the waters – and I should be grateful if you would see to my passports, my friend.'

Arcadius nodded. He went slowly to the window, put aside the curtain and looked out. The little garden was shrouded in soft darkness. The cupid on the stone basin smiled faintly, mysteriously. Jolival sighed.

'If this road did not take you to your godfather, I would not let you go, Marianne. Have you thought of what the Emperor will say? Surely it would have been more natural to go to him first? After all, he is the person most concerned.'

'What else would he do?' Marianne said shortly. 'He would offer me a husband of his own choice – and I could not bear it. I would rather face his anger than submit to his giving me to another. It will be less painful.'

Arcadius de Jolival did not insist. He let fall the curtain and came back to Marianne. For a moment they stood looking at each other in silence, but with a world of affection and understanding in their eyes. Marianne knew that all her own fears about the strange prospect which the Cardinal de Chazay had laid before her had now passed to Arcadius and that he would suffer all the time she was away. Indeed, he was telling her so in a choked voice.

'I hope with all my heart – I hope that Jason Beaufort will come in time. He shall set out again the moment he arrives, and this time I will go with him. But until then, although I am not a religious man, Marianne, I will pray for you, I will pray with all my heart that he will come – come and —'

His feelings overcame him at last and Arcadius de Jolival ran from the room, tears streaming down his face.

Part II

THE MAN IN THE GLOVE

CHAPTER NINE

The Tomb of Ilaria

The rain which had been falling all night and for most of the morning ceased abruptly as the coach left Carrara after a change of horses. The sun broke through the clouds and sent them scudding back towards the mountains, giving way to a wide, sweeping canvas of blue sky. The mountains of white marble which had loomed so dully only a short while before now shone with the dazzling brightness of a glacier carved by some gigantic ice-axe. Blinding arrows of light glanced off every ridge but Marianne was too tired to have eyes for any of it. There was a marble everywhere at Carrara, in rough-hewn lumps, in squared blocks, in slabs, in the white dust lying over everything, even on the tablecloths at the inn where they had snatched a hasty meal.

We supply every court in Europe, in the whole world in fact. Our Grand Duchess sends vast amounts into France. Every single statue of the Emperor comes from here!' The innkeeper spoke with simple pride but Marianne's answering smile was perfunctory. She did not doubt Elisa Bonaparte's willingness to bury her energetic family under tons of marble in the form of busts, bas-reliefs and statues, but she was in no mood today to listen to tales about any of the Bonapartes, Napoleon least of all.

Everywhere on her long journey she had encountered towns and villages decked out, as they had been for a month past, in honour of the imperial wedding. It was an endless succession of balls, concerts and festivities of every description, until it began to seem as if the loyal subjects of his Majesty the Emperor and King would never be done with celebrating a union which Marianne regarded as a personal insult. Their road was lined with a depressing assortment of limp flags, drooping flowers, empty bottles and tottering triumphal arches only too well suited to her own journey, at the end of which lay a marriage to a total stranger which she could not contemplate without revulsion.

The journey itself had been appalling. In spite of Arcadius's anxious protests, Marianne had delayed her departure until the last possible moment, still hoping that Jason would arrive in time. In the end it was not until dawn on the third of May that she climbed into her coach. As the four powerful horses drew the berline over the cobbles of the rue de Lille and Arcadius's troubled face and waving hand were lost in the morning haze, she felt as if she were leaving a part of herself behind. It was like leaving Selton all over again and this time too the future looked grim and uncertain.

In order to make up for lost time and avoid being late at the appointed meeting place, she travelled at breakneck speed. For three days, until they reached Lyon, she refused to stop for anything except to change horses and for the briefest of meals, paying the postillions two or three times the normal rate to encourage them to make better speed. They galloped on regardless of deeply rutted roads that sometimes degenerated into a sea of mud, and still Marianne leaned perilously out of the window to look back at the road behind them. But whenever a horseman did come in sight, it was never the one she hoped for.

After a few hours' rest at Lyon, the coach began climbing towards the mountains and was forced to slow its killing pace. The new road across Mont Cenis, begun by Napoleon seven years before, had been advised by Arcadius because it shortened the distance considerably. But the work was only recently completed and the crossing was an uncomfortable one for Marianne, Agathe and Gracchus, who were obliged to go a good deal of the way over the pass on foot while the coach was drawn by mules. Yet for all that, thanks to the comforting welcome they received from the monks of the hospice, and thanks, still more, to the splendours of the mountain scenery, which she beheld for the first time in her life, Marianne found here a brief respite from her troubles. There was something a little intoxicating, perhaps, in the knowledge that her coach was, if not actually the first, certainly only the second or third to travel that way. She did not feel in the least tired and, forgetting the need for haste, she sat for a long time beside the blue waters of the lake at the top of the pass, conscious of a strange yearning to remain there for ever breathing in the pure air and watching the slow flight of the jackdaws, black against the snowy majesty of the peaks. Time, here, stood still. It would be easy to forget the noise and deceits and complications of the world, its furies and its heartbreaks. There were no faded banners here, no popular songs, no trampled flowers to destroy the harmony of the scene, only the blue stars of gentian in the crevices of the rocks, and the silver lace of lichen. The bare, almost barrack-like shape of the hospice, it too enlarged by the Emperor, seemed to take on a kind of nobility, a strangely mystical air, as if its stern walls were illumined by the prayer and charity that dwelt within. Not until one of the monks came and laid his hand gently on her arm to remind her that an exhausted maid and a half-frozen coachman were waiting for her by the coach, now ready for the descent, did she consent to continue her journey to Susa.

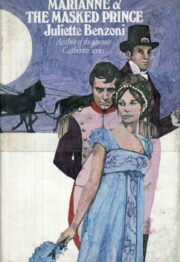

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.