'But I am not going. While my friend Philibert, accompanied by the Abbé Bichette, is travelling peacefully to Rheims in the coach, escorted by the Duc de Rovigo's men, I shall be disguised as a servant and riding hard for Italy where the Holy Father is waiting for me to report to him about a certain mission.'

Still clutching the precious letter which spelled a year of freedom to her, Marianne stood speechlessly staring at the two cardinals, the real and the false, wondering if she had ever really known Gauthier de Chazay. Who was this man who had fought with such determination to save her as a baby, who, although he certainly possessed no fortune of his own, was able with a stroke of the pen to pay out a prince's ransom, and who travelled the roads on horseback dressed as a servant?

Evidently the one-time Abbé had noticed his god-daughter's bewilderment, for he went to her and kissed her affectionately.

'Do not try to understand what is outside your comprehension, Marianne. Just remember that you are still my beloved child and that I want you to be happy, even if the means I use to procure your happiness do not meet with your approval. God keep you, my child. I will pray for you as I have always done.'

He blessed her quickly and then turned away to open the window.

'This is the swiftest way to reach the stables without meeting anyone,' he said. 'Good-bye, my dear Philibert. Send Bichette back to me, you know where, when you can spare him. I hope you will not have to suffer for our little deception.'

'Have no fears. The escort will notice nothing. I will hide my face as far as possible, and fortunately neither of us is well known. Your brethren of the Sacred College may be a trifle surprised but I will explain matters to them and in a few days I shall find the means to return here, in my real identity. Have a good journey, my dear Chazay, and convey my filial regards, respect and obedience to the Holy Father.'

'I will. Marianne, farewell. My regards to that silly creature Adelaide when you find her. We have never seen eye to eye but I have a fondness for her just the same.'

Whereupon his Eminence threw one leg over the window-sill and jumped down into the courtyard. Marianne saw him vanish swiftly through the darkened doorway of the coach house below the tower. Canon de Bruillard made her a little bow.

'Do not worry about him. He will leave by way of the Seine. And now permit me to leave you also. The Abbé Bichette is outside and the escort is waiting below.'

He was donning a voluminous cloak as he spoke, turning up the collar so as to conceal the greater part of his face. Then, with one last nod of farewell, he left the library. As the door opened, Marianne caught sight of the Abbé Bichette, looking more like a frightened chicken than ever. Crossing to a barred window, she saw a large travelling coach with lighted lamps drawn up in the street below, surrounded by a platoon of mounted men in black cocked hats with red cockades, the horses' hooves striking sparks from the ancient cobbles. This display of military strength for the sake of two peaceable servants of God struck her as absurd and at the same time intolerable. But when she remembered the casual way in which Gauthier de Chazay had climbed out of the window and felt the letter in her hand, she thought again. Surely the little cardinal, so frail and harmless to all appearances, represented an infinitely more active and formidable power than she could ever have imagined? He seemed to command men and events like God himself. In a month a man would be prepared, at his command, to marry her, Marianne, a total stranger and pregnant into the bargain. Why? What for? By what authority?

A dash of arms outside called Marianne from her thoughts and she saw the small, red figure of the pseudo-cardinal climb into the coach, followed by the tall, lean one of the Abbé who crossed himself several times at the sight of the captain in charge of the escort, as if he had seen the devil. She heard the door slam shut in the darkness, the crack of the whip, and then with a thunderous roar the coach and its escort swept away down the rue Chanoinesse. Behind her, Marianne heard the measured tones of the footman who had admitted her earlier.

'If madame will allow me to see her to her coach? I have to shut the house now.'

She picked up her cloak, which she had laid over the back of a chair, and put on her gloves, stowing the precious letter carefully in an inner pocket.

'I am ready' she said.

Now that her godfather had gone and she was alone Marianne felt the full weight of her misery. A month! In a month she would be married – to a complete stranger perhaps. It was true that she was free to choose for herself if she wanted to avoid giving her hand to the unknown man whose name, true to the love of mystery which she had always found in him, her godfather had refused to divulge. The Abbé de Chazay had been the most secretive of men and it seemed that the Cardinal San Lorenzo shared his uncommunicative habit. No, at all costs, she must find someone, someone who did not fill her soul with loathing, a man for whom she might feel, if not love, at least respect. She had always known that girls of her station married, more often than not, without meeting their betrothed. It was a matter for their families. It might have been expected, after all, that this would be her own fate, but the independence she had acquired through the blows fate had dealt her made it impossible for her to yield without a struggle. She wanted to choose for herself. But who?

As she followed the footman with his heavy candlestick through the darkened rooms, Marianne was mentally reviewing the men to whom she might turn. Fortunée had told her that the whole of the Imperial Guard was in love with her but she was unable to identify a single face, a single person to whom she might turn for help. She hardly knew them and there was no time now to further an acquaintance. Moreover, some were no doubt married and others had no desire to be, especially under such conditions; Marianne was wise enough to know that it was a long way from paying court to her to marriage. Clary? The Austrian prince would never marry an opera singer. In any case, he was already married to the daughter of the Prince de Lignes, and even if he were not, Marianne would never willingly become a fellow-countrywoman of the hated Marie-Louise. What then? It was out of the question to ask Napoleon to find her a husband, for the reasons put forward by the cardinal, and besides her feelings revolted at the idea of being bestowed by the man she loved on someone who could only be a complaisant husband. Better the unknown chosen by her godfather, who had at least promised that he would be irreproachable.

It occurred to her momentarily that she might marry Arcadius but even in her misery the idea was enough to make her smile. No, she could not imagine herself as Madame de Jolival. It would be like marrying her own brother, or perhaps an uncle.

Then, when she reached the street and saw Gracchus-Hannibal Pioche in the act of letting down the steps of her carriage the answer came to her in a sudden, blinding flash. Side by side with the boy's chubby face and thatch of carroty hair she saw, by association, another face. The vision was so clear that she said out loud: 'He! He is the man I need.'

Gracchus turned, hearing her voice. 'What is it, Mademoiselle Marianne?'

'Nothing, Gracchus. Tell me, can I count on you?'

'Need you ask, mademoiselle? Only tell me what I must do.'

Marianne did not hesitate. She had made her choice and she felt a sudden sense of relief.

Thank you. Indeed, I did not doubt it. Listen, when we get home I want you to change into travelling clothes and saddle a horse. Come to me then and I will give you a letter which I want carried as quickly as you can.'

'I will stop for nothing but to change horses. Is it far?' To Nantes. But first, home, Gracchus, as fast as you can.'

An hour later, Gracchus-Hannibal Pioche, heavily booted and enveloped in a thick riding cloak that would withstand the heaviest downpour, a hat pulled down over his eyes, clattered through the gates of the Hôtel d'Asselnat. Marianne watched him go from an upstairs window and it was not until Augustin, the porter, had shut the heavy gates behind him that she left her post and made her way back to her own room where the smell of hot wax still hovered in the air.

Automatically, she went straight to her small writing-table and closed the blue morocco folder, first carefully extracting the single sheet of paper, signed only with an 'F', which had lain there. This letter, which had been waiting for her when she returned from the rue Chanoinesse, appointed a meeting for the following evening to hand over the fifty thousand livres. Marianne had an impulse to burn it but the fire in the hearth had gone out and then it crossed her mind that she should perhaps show it to Jolival, who at that late hour had still not come in. She thought he was probably trying to find the money for the ransom. The few words in Francis's handwriting had no power to wrest a shiver from Marianne. She read them indifferently, as though they did not really concern her. All her thoughts, all her anxieties, were concentrated on the letter she had just written and which Gracchus was at that moment carrying on its way to Nantes.

It was, in fact, two letters. One was addressed to Robert Patterson, United States consul, requesting him to speed the second letter to its destination with the utmost urgency. Even so, Marianne did not attempt to conceal from herself that the second letter was a little like the message in a bottle cast by a shipwrecked mariner into the waves. Where was Jason Beaufort at that moment? Where was the vessel whose name Marianne had refused to ask? A month was such a short time and the world so wide. Yet, however hopeless the odds, Marianne had been unable to prevent herself from writing that letter summoning to her side the man she had so long believed she hated and who now seemed to her the one being strong, reliable and true enough, the one man she dared ask to give his name to Napoleon's child.

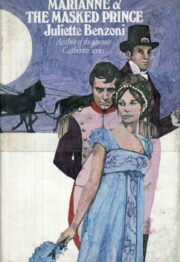

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.