'I should not be here else. And so – I may count on such a sum, the day after tomorrow perhaps?'

'Indeed you may. In the afternoon, shall we say?'

'No, that will not be possible. I am to sing at the Tuileries before – before their majesties.'

She stumbled on the plural but she got it out somehow. Ouvrard listened with a beatific smile.

'In the evening, then? After the reception? I will expect you at my house. That will be even better. We can talk – get to know one another.'

The colour flamed in Marianne's cheeks. She rose quickly, snatching back her hands which the banker still held. It had dawned on her suddenly on what conditions Ouvrard was prepared to advance her the money. Quivering with anger, she burst out: 'Monsieur Ouvrard, I do not think we understand one another correctly. This is a loan merely. I will repay you the twenty thousand livres within three months.'

The banker's pleasant face was crossed by a momentary frown. He shrugged.

'Who spoke of a loan? A woman such as you may make what demands she pleases. I will give you more if you wish.'

'I do not want any more – and that only as a loan.'

The banker sighed and getting to his feet moved heavily to where Marianne had prudently retreated to the chimney-piece. His voice had lost its honeyed tones and there was a strange flicker in his eyes.

'Leave such matters to men, my dear, and take what is offered you in good faith.'

'In return for what?'

'For nothing – or nothing to signify. A little friendship, an hour of your company, the right to look at you, breathe in your fragrance…'

Again his hands groped towards her eagerly, ready to hold and caress. The banker's sallow face had turned brick red above his snowy cravat and his eyes rested greedily on the beautiful, bare shoulders before him. A tremor of disgust ran through Marianne. How could she have been such a fool as to apply to this man with his dubious history, and who had barely emerged from prison? It was madness!

'What you ask,' she said hastily, in a desperate attempt to frighten him, 'is impossible. The Emperor would never forgive either of us. You must know that I am – an imperial perquisite.'

'Perquisites cost money, signorina. Those who enjoy them must be aware of this and take steps to see that no one can outbid them. In any case, think about it. You are tired tonight, and clearly under some stress. Today's wedding must have been very trying for a – perquisite! But do not forget that twenty thousand livres, or more, will be waiting for you at my house the day after tomorrow, all night if need be, and all the next day.'

Without a word or even a glance, Marianne turned on her heel and went to the door. Her pride and dignity made her look like an insulted queen, but there was despair in her heart. What had seemed her last remaining chance to obtain the money was gone, for she would never, never agree to accept Ouvrard's conditions. She had thought, in her innocence, that he would make her a friendly loan but now she realized once again that with men all transactions came down to the same thing, when the woman concerned was young and pretty. 'I know a dozen men who would give as much for one night with you,' was what Fortunée had said and Marianne had thought she was joking. How much had Madame Hamelin known about Ouvrard's intentions? Was it in order that the proposition could be put to Marianne directly that she had not concluded the matter herself? Marianne found it hard to believe that her friend could have led her so cruelly into a trap so repugnant to her, knowing her as she did.

Her question was answered sooner than she expected. She was on the point of leaving the room when Ouvrard's voice made her pause.

'Do not forget: I shall be waiting. You understand, of course, that there is no need to tell our friend Fortunée about our little agreement. A delightful creature, but inclined to be jealous!'

Jealous? Fortunée? At that moment, Marianne almost forgot her anger and laughed in his face. Did this absurd little man really believe that he had power to attach that exotic creature to himself alone? She had an irresistible urge to throw in his face the information that this 'delightful' but 'jealous' creature was in all probability even then revelling in the arms of the handsome soldier who was her heart's delight. Just to see what he would say.

But Madame Hamelin conducted her life according to her own rules and not for anything would Marianne have caused her the slightest trouble. Besides, it was a relief to know that she was unaware of Ouvrard's little plan and of the terms of the bargain he meant to offer. Marianne was beset by a fresh temptation: to go and warn her instantly, and this she would most probably have done, had Fortunée been alone. But Marianne had no wish for a fresh encounter with the insolent Fournier, much less to interrupt the lovers' tete-a-tete.

'Tell Madame Hamelin I will see her tomorrow,' was all she said to Jonas when he appeared at her side, 'that is, if she is receiving callers.'

'But Mademoiselle Marianne, you are not going out like that? Wait while I call for the carriage.'

'No need, Jonas. I can see my own carriage arriving.'

It was true. A glance through the hall windows had shown her Gracchus-Hannibal bringing the chaise round in sweeping style to draw up at the steps. But even as Jonas tenderly arranged a handy cashmere shawl about Marianne's shoulders, his eyes widened at the sight of Arcadius descending from the carriage.

His black coat was torn, shreds of lace hanging from his shirt front, his fine silk hat completely stove in, one eye blackening nicely and countless scratches on his face: the Vicomte de Jolival showed all the signs of a glorious combat, while Gracchus sat upright on his box, hatless and dishevelled, extremely red of face and bright of eye, wielding his whip with a triumphant flourish.

'Well,' Marianne said, 'so here you are! Where have you been?'

'In the crowd, where you left us,' Jolival growled. 'You look a good deal fresher than we do, but I thought you were wearing a pink dress when we started out?'

'That met with some adventures, too. But let us go home, my friend. You need a bath and some attention to that eye. Home, Gracchus, as quick as you can.'

'If you want me to spring 'em, mademoiselle, we'll have to go through the wall by the Fermiers Généraux and half-way round Paris.'

'Go which way you please, but take us home and avoid the crowd.'

As the carriage swept out of the courtyard once more, Arcadius held his handkerchief to his swollen eye again.

'Well?' he asked. 'Did you get anything?'

'Ten thousand livres which Madame Hamelin offered me at once.'

'That was kind – but not enough. Did you try Ouvrard as I suggested?'

Marianne pursed her lips and frowned at the recollection of what had passed.

'Yes. Fortunée paved the way for me, but we could not agree. He – his charges are too high for me, Arcadius.'

There was a short silence, spent by Jolival in weighing up the implications of these words, which he had no difficulty in interpreting correctly.

'Ah,' was all he said. 'And – does Madame Hamelin know the terms of this bargain?'

'No. Nor is it intended that she should. I would have told her at once, of course, only she was very much occupied.'

'With what?'

'With a certain wounded soldier who dropped on her like a chimney-pot in a gale and who seems to hold a high place in her affections.'

'Fournier, I know. So the hussar has returned? For all his dislike of the Emperor, he can never bear to stay long away from the field of action.'

Marianne uttered a small sigh. 'Is there anything you do not know, my friend?'

Jolival achieved a painful grin in spite of his scratches, and stared gloomily at the ruins of his hat.

'Yes, such as, for instance, how we are to procure the twenty thousand livres that we need?'

'There is only one way left. My jewels. Even if it does mean trouble with the Emperor. You must see if you can pledge them tomorrow. If not, they must be sold.'

'You are making a mistake, Marianne. Believe me, you had better go to the Emperor. Ask for an audience and, since you are to sing at the Tuileries the day after tomorrow…'

'No! Definitely not! He questions too shrewdly and there are things I would not have him know. After all,' she added sadly, 'it is true I am a murderess. I killed a woman, unintentionally, but I killed her. I cannot tell him that.'

'Do you think he will not ask questions if he hears that you have sold his emeralds?'

'Try and arrange to buy them back in two or three months' time. I will sing wherever I am asked. You find me the contracts.'

'Very well,' Jolival sighed. 'I will do my best. Meanwhile, take this.'

He felt in the pocket of his battered white waistcoat and extracted something round and shining which he slipped into Marianne's hand.

'What is this?' she said, leaning over to see it more clearly in the darkness of the chaise.

'A little souvenir of a memorable day,' Jolival said sardonically. 'One of the medals they were throwing to the crowd. I won it in fair fight. Take care of it,' he added, dabbing once more at his swollen eye, 'it cost me dear.'

'I am sorry about your eye, my poor friend, but one thing you may be sure of: even if I live to be a hundred, I shall never forget today.'

CHAPTER FIVE

Cardinal San Lorenzo

Faithful to his self-appointed role of cicisbeo, Prince Clary presented himself on the following Wednesday ready to escort Marianne to the Tuileries. But as the ambassadorial carriage drove them there, Marianne did not fail to notice that her companion seemed preoccupied. The young man's forehead was wrinkled below his fair hair in an anxious frown and his candid smile was without its usual gaiety. When she taxed him gently with it, he made no effort to deny it.

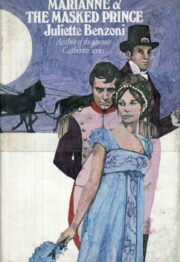

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.