When Marianne got back to her room, she was surprised to find her cousin there. Mademoiselle Adelaide d'Asselnat, dressed in a loose wrap of puce velvet with an immense fluted cap adorning her head, was standing in the middle of the room contemplating, with interest but no apparent surprise, the glorious debris of the white dress left lying crumpled on the carpet.

'Adelaide, you here? I thought you were asleep long ago.'

'I always sleep with one eye open and something warned me you might need a little company when "he" had gone.' The old maid sighed and picked up the scrap of pearly satin. 'Ah, now there's a man who has a way with women! I do not wonder you should fall for him. I did myself, you know, when he was only a shabby, underfed little general. But tell me, how did he take the sudden resurrection of your late lamented husband?'

'Badly,' Marianne said, rummaging among the ravages of her bed for the nightgown which Agathe, her maid, must have laid out to await her return from the theatre. 'He is half-convinced that I was seeing things.'

'You were not?'

'No! Why should I suddenly see Francis's ghost when he was a hundred miles from my thoughts? I thought him dead. No, I am sorry, Adelaide, but there could be no mistake; it was Francis, certainly… and he was smiling, smiling at me in a way that terrified me! God knows what he means to do.'

'Time will tell,' the spinster said placidly, moving in a purposeful way towards the small table with a lace cloth on which a cold supper had been left ready for Marianne, although neither she nor the Emperor had eaten a mouthful. Calmly, Adelaide uncorked a bottle of champagne and filled two tall glasses. One of these she emptied at a draught, the other she carried over to Marianne, after which she returned for her own glass, selected a wing of chicken from the dish, and settled herself comfortably on the foot of the bed in which her cousin was by now ensconced.

Marianne sat propped up on her pillows, glass in hand, and regarded Adelaide with an indulgent smile. The amount of food which that frail, bird-like creature could absorb was quite amazing. All day long Adelaide was nibbling, sipping or toying with 'a little something', none of which deterred her in the least from sitting down to table with undiminished enthusiasm when the time came. Yet for all this she never seemed to put on an ounce of weight or lose one jot of her dignity.

The strange, nervous, cantankerous creature whom Marianne had found in the salon late one night about to set fire to the house had completely disappeared. She had been replaced by a woman no longer young but whose backbone had recovered all its innate rigidity. Well-dressed, her soft grey hair neatly combed into long, silky ringlets that peeped below her voluminous lace caps and velvet hoods, the erstwhile revolutionary who had been sought by Fouché's police and kept under house arrest had become once again Adelaide d'Asselnat, a great lady. At the present moment, however, she was sitting with half-closed eyes, aristocratic nostrils quivering with greed, consuming chicken and champagne with the dainty self-satisfaction of a contented cat. Marianne could not help smiling. While not perfectly sure that her cousin's conspiratorial instincts were altogether buried, Marianne had grown very fond of Adelaide.

She sipped her champagne slowly, waiting for the old lady to speak. She guessed that Adelaide had something to say to her, and, sure enough, having reduced the chicken to bare bone and drunk the champagne down to the final drop, Adelaide wiped her lips with satisfaction and bent her blue gaze earnestly on her cousin.

'Dear child,' she began, 'I think you are looking at your problem from the wrong angle. I gather that your late husband's unexpected resurrection has thrown you into a dither and now that you have seen him you are living in terror of his appearing to confront you again. Is that it?'

'Of course it is! But I don't understand, Adelaide. Do you think I ought to be overjoyed at the return of a man I believed I had punished as he deserved for what he did to me?'

'Well, yes, in a way.'

'But why?'

'Because now that he is alive you are no longer a murderess and need not fear pursuit from the law in England.'

Marianne smiled. 'I was not much afraid of it,' she said. 'Apart from the war, the Emperor's protection is more than enough to remove all my fears. But you are right in a way. It is nice to know there is no blood on my hands.'

'Can you be sure of that? There is still the pretty cousin you stunned so neatly…'

'I can hardly have killed her. If Francis is alive, I would wager that Ivy St Albans is alive as well. Besides, Francis means nothing to me now and I have no reason to desire her death.'

'He is still your lawfully wedded husband, my dear. That is why, if I were in your shoes, instead of running away from your ghost, I should do my best to meet him again. When citizen Fouché calls on you in the morning —'

'How did you know I was expecting the Duke of Otranto?'

'I shall never become accustomed to calling that unfrocked priest by that title. But, of course, he is bound to come tomorrow… Oh, don't look at me so! Naturally I listen at keyholes when I want to know what is happening inside.'

'Adelaide!' Marianne was genuinely shocked.

Mademoiselle d'Asselnat stretched out her arm and patted Marianne's hand.

'Don't be such a little prude. Even an Asselnat may listen at doors. It can be very useful, as you will find. Where was I?'

'You were saying that the – the Minister of Police would call.'

'Ah yes. Well, instead of begging him to lay hands on that precious husband of yours and send him back to England on the first frigate, you must ask him, on the contrary, to bring him to you so that you may inform him of your decision.'

'My decision? Have I decided anything?' Marianne was more and more at sea.

'Of course you have. I wonder you should not have thought of it yourself. And while you have the minister to hand, ask him to try and find out what has become of your reverend godfather, that Jack-of-all-trades, Gauthier de Chazay. We shall be wanting him shortly. Even while he was still a little nobody of a priest he had the Pope in his pocket, and you can't imagine how useful the Pope can be when it comes to dissolving a marriage. Are you beginning to understand now?'

Marianne was indeed beginning to understand. Adelaide's idea was so brilliant and so simple that she scolded herself for not thinking of it sooner. The marriage was never consummated and besides it had been contracted with a Protestant: it should be possible, even easy, to get it annulled. Then she would be free, wholly, wonderfully free, without even her husband's death upon her conscience. But even as she called to mind the grave little figure of the Abbé de Chazay, Marianne was conscious of a creeping uneasiness.

She had thought of her godfather so often in the time since she had stood on the quay at Plymouth and gazed despairingly after the little vessel's fast-disappearing sails. She had thought of him sadly but hopefully at first, but a slight anxiety had grown with the passage of time. What would he say, that man of God, so fiercely upright in all matters of honour, so blindly loyal to his exiled king, if he knew his god-daughter was masquerading as Maria Stella, an opera singer and the Usurper's mistress? Would he ever understand what it had cost Marianne in suffering and blighted hopes to reach her present state and the happiness it held for her? Certainly if she had caught up with the Abbé on the Barbican at Plymouth her destiny would have been a very different one. He would probably have gained admittance for her to some convent where she would have been given every opportunity, in prayer and meditation, to expiate what she had never ceased to regard as the righteous execution of her husband. But although she had often thought of her godfather's affection and goodness with real regret, Marianne was well aware that she did not in the least regret the life that would have been hers in the convent.

Finally, Marianne put something of her doubt into words by saying to her cousin:

'It would make me more than happy to see my godfather again, cousin, but don't you think it would be selfish of me to seek him out merely to get my marriage annulled? Surely the Emperor —'

Adelaide dapped her hands.

'But what a good idea! Why did I not think of it? Of course, the Emperor is the very man!' She went on in an altered tone: 'The Emperor on whose orders the Pope was put under arrest by General Radet, the Emperor who kept the Pope a prisoner at Savona, the Emperor who was excommunicated by His Holiness last June in his splendid bull "Quum memoranda" – the Emperor is the very man we need to present a request for annulment to the Pope. He could not even procure the dissolution of his own marriage to that poor, sweet Josephine!'

'Oh,' Marianne said, crestfallen. 'I had forgotten. But do you really think my godfather… ?'

'Will get you your dissolution for the asking? I don't doubt it for an instant. We have only to discover the dear Abbé and all will be well. Liberty!'

Adelaide's rush of enthusiasm inclined Marianne to attribute some of her optimism to the champagne, but there was no doubt the old lady was right and that their best recourse in this situation was to rely on the Abbé de Chazey, although it was disappointing to discover a field in which Napoleon was not all-powerful. But how soon could the Abbé be found?

Fouché snapped shut the lid of his snuff-box, restored it to his pocket and shook out his lace ruffles with old-world grace.

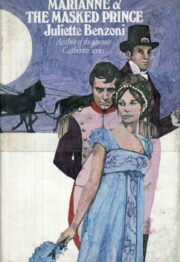

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.