'What then?'

'Then,' Jolival said, very softly, 'supposing the Emperor is unable to offer you his head, I think we may have to take it ourselves.'

With the utterance of this cool sentence of death, Arcadius leaned forward and tapped with his cane on the glass.

'Ho there, Gracchus!'

The coachman's round, youthful face appeared.

'Monsieur le Vicomte?'

'To the Tuileries, my lad.'

The words roused Marianne from her contemplation of her friend's pronouncement. She started.

'The Tuileries? What for?'

'Have you forgotten you are engaged to meet Count Clary? He has promised to take you into the grand gallery of the Louvre to see the imperial pair leave the chapel?'

'Do you really think,' Marianne burst out, glad of the chance to relieve her feelings, 'that I have any intention of taking a closer look at this – this masquerade?'

Arcadius threw back his head and laughed.

'I see you have duly appreciated our Emperor's efforts at sartorial splendour. Yet it will be a fine sight, even so…'

'… and you may as well tell me straight out that you wish to be rid of me! What are you up to, Arcadius?'

'Nothing very much. I have a little business to attend to and I was hoping that if you did not require the carriage you would let me take it.'

'Take it by all means, but take me home first. Gracchus! We are going home.' Marianne rapped on the glass in her turn. She was curious to know just what it was that Jolival had found to do so urgently but she knew from experience that it was practically impossible to make him talk when he had made up his mind to say nothing.

Marianne's carriage swung round to make its way back across the Concorde bridge. The crowd, which had been so dense while the procession was passing, had thinned a little and most of the people were drifting away through the gardens or along the river towards the palace of the Tuileries, where the imperial couple were to show themselves on the balcony. Marianne, however, had no wish to see the ill-assorted pair again. Had Napoleon taken to wife a princess who matched up to her ideas of what a princess should be, a thoroughbred worthy to be the mother of an emperor, the aristocrat in Marianne would have taken a kind of painful pride in the event. But this blonde pudding with her cow-like expression! How could he gaze at her with such apparent joy and pride? Even the people had sensed it. Perhaps because the graceful and delicate image of Josephine was still before their eyes, the crowd had given the newcomer only a perfunctory acclaim. The cheering had been scattered and lukewarm. How many were there in that crowd, moreover, who were now greeting Marie-Louise in the very spot where, seventeen years earlier, they had watched the execution of Marie-Antoinette? How could the people of Paris feel anything but uneasy suspicion for this new Austrian, so pitiful a caricature of that radiant princess of an earlier day?

Marianne and Jolival sat in silence as the carriage proceeded across the bridge, and then past the new classical façade of the Palais du Corps Legislatif,[2] still shrouded in scaffolding, to the rue de Lille. Both were locked in their own thoughts and each respected the other's silence.

When the vehicle drew up before the newly restored front entrance to the Hôtel d'Asselnat, however, Marianne could not help asking as she gave her hand to Jolival to descend from the carriage: 'Are you sure you would not like me to come with you on this – this urgent business?'

'Quite sure,' Arcadius answered smoothly. 'Go in and sit by the fire like a good girl and wait for me, and do try not to worry. We may not be altogether as helpless as Lord Cranmere likes to think.'

An encouraging smile, a bow, a nourish and the Vicomte de Jolival had disappeared into the carriage which was already turning back towards the street. Marianne gave a little shrug and trod up the steps to where a servant was holding the door for her. Wait like a good girl – not to worry – it was like Jolival to give her that advice. But it was dreadful to have to return to the house when Adelaide was not there, dear, irritating, wonderful Adelaide, with her insatiable appetite and never-ending fund of gossip.

As it turned out, she had no time to wonder what she should do with herself until Jolival's return. As she reached the marble staircase that led to her own room she was met by her butler, Jeremy, stiff and solemn as ever in his dark green livery. Marianne was not over-fond of Jeremy, who never smiled and always seemed to have some unwelcome news up his sleeve, but Fortunée, who had chosen him, maintained that to employ a person of such lugubrious and distinguished bearing lent tone to a house. Jeremy bowed, his aquiline features a mask of boredom and gloom.

'Monsieur Constant awaits madame in the music room,' he murmured apologetically, as though confiding some shameful secret. 'He has been waiting for rather more than an hour…'

A sudden wave of happiness swept over Marianne. Constant! Napoleon's faithful valet, the man most in his confidence and now, to Marianne, the guardian of what seemed a kind of Paradise Lost. Surely fate could have offered no better answer to her present anxiety and the agonizing days ahead? Constant's presence in her house meant that even on this day of days, Napoleon had thought of her in her loneliness and perhaps the Austrian's hold on him was after all less than Parisian gossip would have it.

Marianne cocked an eyebrow quizzically at her butler.

'I may as well tell you, Jeremy, that M. Constant's visit is very welcome, so there is no need to announce it as if it were a disaster of the first magnitude. You should smile, Jeremy, when you announce a friend, smile – do you know what that is?'

'Not altogether, madame, but I will endeavour.'

CHAPTER FOUR

Madame Hamelin's Lovers

With the patience that characterizes the northerner, Constant had sat down to wait in what comfort he could for Marianne's return. He even fell into a doze, ensconced beside the fire with his feet on the fender and his hands clasped on his stomach. He was roused by the sound of Marianne's quick footsteps on the tiled floor outside and by the time the girl entered the music room he was on his feet, bowing respectfully.

'Monsieur Constant! I am so sorry to have kept you waiting. I am so glad to see you, and today of all days! I should have thought no force on earth would have dragged you from the palace.'

'No occasion is important enough to outweigh the Emperor's orders, Mademoiselle Marianne. He commands – and behold, I obey. As for keeping me waiting, think nothing of it. I have been enjoying the peace of your house as a change from all the excitement.'

'He thought of me,' Marianne said involuntarily, shaken by this unexpected happiness, coming on top of the horror she had experienced in the place de la Concorde.

'Indeed – I believe his majesty thinks of you very often. At all events,' he continued, declining the seat to which his hostess waved him, 'I am charged to deliver my message to you and return to the palace forthwith.' He moved across to the harpsichord and picked up the heavy canvas bag which lay there. 'The Emperor instructed me to hand you this, Mademoiselle Marianne, with his compliments. It contains twenty thousand livres.'

'Money?' she exclaimed, flushing. 'But —'

Constant allowed her no time to protest.

'It occurred to his majesty that you might be in need of funds at this present time,' he said, smiling. 'Moreover, this is in the nature of a remuneration for your services which I am to engage for the day after tomorrow.'

'The Emperor wishes me to —'

'To sing at the reception to be held at the Tuileries. I have the invitation here.' He drew the card from his pocket and presented it to Marianne. Ignoring it, the girl clasped her arms across her breast and went slowly to one of the windows overlooking the small garden. The fountain pattered softly into the grey stone basin, under the smiling gaze of the cupid on the dolphin. Marianne watched it for a moment without speaking. Disturbed by her silence, Constant came towards her.

'Why don't you answer? You will come, of course?'

'I – Constant, I do not want to! To be obliged to curtsey to that woman, sing for her – I couldn't.'

'I am afraid you must, however. The Emperor was far from pleased that you did not come to Compiègne and Madame Grassini suffered for his displeasure. If you fail him this time you must be prepared for his anger.'

'His anger?' Marianne swung round suddenly. 'Can't he understand how it feels to see him with that woman at his side? I was in the place de la Concorde just now and I saw them ride past, smiling and triumphant and so full of happiness that it hurt. He makes himself ridiculous to please her! That absurd dress, that head-dress —'

'Oh, that dreadful head-dress,' Constant said, laughing. 'It certainly gave us some trouble. Half an hour it took us to set it at a reasonable angle – and even then, I confess, it was not a success.'

Constant's good humour did something to relax Marianne's nerves but her evident distress had not escaped the Emperor's valet and it was in a more serious tone that he continued:

'As for the Empress, I think that you, like all of us, must regard her simply as the symbol and promise of a future dynasty. It is my sincere belief that the Emperor is inclined to value her birth above her person.'

Marianne shrugged.

'Indeed!' she said sullenly. 'I have heard that after that famous night at Compiègne, he took one of his associates aside and told him: "Marry a German, my friend, they are the best women in the world: sweet, kind, innocent and fresh as roses!" Did he say that or no?'

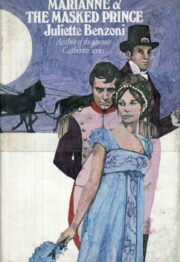

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.