'Here comes the procession,' Francis observed, settling himself more comfortably, in the manner of one intending to remain. We shall have to continue our talk later on. It is impossible to converse in this uproar.'

This was true. An incredible river of dazzling, coruscating colour was flowing down the Champs Elysées, advancing majestically towards the Tuileries amid a clamour of brass bands playing, drums rolling and cannon roaring, greeted by waves of cheering and cries of 'Long live the Emperor!' The whole great square, so packed with people that the bright colours had all merged into a uniform, grey blue, appeared to give one mighty heave. Around her, Marianne could hear those nearest exclaiming as the procession passed by.

'Those are the Polish Light Cavalry in front!'

'How handsome they are! Some of them must be thinking of Marie Walewska today!'

Red, blue, white and gold, snowy plumes waving on their square shakos and the tips of their long lances gleaming fiery red and gold, Prince Poniatowski's troops rode past in perfect formation, holding the powerful white horses that were a familiar sight on every road in Europe well in hand. After them came Guyot's Chasseurs in purple and gold, alternating with troops of Mamelukes, girded with shining steel, their dark skins and white turbans surmounted by black aigrettes, and the panther skins over their saddles adding a touch of barbaric splendour. Next came the Dragoons, commanded by the Comte de Saint-Sulpice, dark green and white, magnificently whiskered, their black-plumed helmets shining in the sun. Next, red, green and silver, the Guards of Honour, preceding a long file of thirty-six gorgeous golden coaches bearing the imperial family and the highest officers of the court.

As though in a dream, Marianne scanned the amazing kaleidoscope of colour that was the Emperor's staff, his marshals, aides-de-camp and equerries, picking out Duroc, a blaze of gold, Massena, LeFebvre and Bernadotte, all of whom she had seen more than once in Talleyrand's house. She saw Murat in a purple uniform thickly encrusted with gold braid, sable-lined cloak swinging from his shoulder, glittering like a firework display from his spurs to his diamond cockade. Despite his overweening pride in his own magnificence, he was a figure that compelled admiration for the consummate horsemanship which enabled him to manage his mettlesome Arab stallion with such apparent ease.

The shimmering cavalcade moved on, a tide of men and horses and splendid carriages. Most sumptuous of all, drawing a gasp of admiration from the crowd, was the great, gilded coach drawn by six white horses that rolled on its stately way surmounted by an imperial crown. This was the Empress's state coach. But although the harness gleamed and the windows flashed with reflected sunlight, no figure waved from within. The coach was empty. For this day the imperial pair had elected to ride together in an open carriage. The barouche that carried Napoleon and Marie-Louise followed immediately after this gilded monument to imperial grandeur. Marianne stared at it with eyes grown suddenly round with amazement, while the crowd were hushed. All were stunned by the vision that met their eyes.

Marie-Louise sat in the carriage smiling vaguely about her and waving in an ungainly, mechanical way. Her face, under the massive crown of diamonds, was very red and she was dressed in a masterpiece of Leroy's handiwork, a magnificent gown of silver tulle literally covered in diamonds. As for Napoleon, seated beside her in the carriage, his appearance was so different from that he normally presented that for a moment Marianne was startled into forgetting Francis.

Accustomed to the extreme simplicity of his habitual dress, the black or grey coat of a colonel in the Chasseurs or the Guards, Marianne could hardly believe that the figure waving and smiling from the barouche was indeed the man she loved. He was dressed in the Spanish fashion with a short cloak of white satin liberally sprinkled with diamonds and he, too, had on his head an incredible confection of black velvet and white plumes, circled with eight rows of diamonds, which seemed to maintain itself upright in defiance of gravity. The head-dress had an impromptu, vaguely Renaissance air which Marianne found preposterous, and wholly unsuited to the pale, clear-cut features of the latter-day Caesar. How could he ever have consented to dress himself up like that and what —

A shout of laughter broke in on her thoughts. She turned on Francis wrathfully, not altogether sorry to have someone on whom to vent her rage and disappointment. He was lying back against the squabs, laughing unrestrainedly.

'May I ask what you find to amuse you?'

'What – oh no, my dear. Don't tell me you don't find Boney's fancy dress very funny? It is so dreadful, it is sublime! I've never seen anything so comical! I could weep with laughter! It's – it's unbelievable!'

Marianne fought back the impulse to fly at him tooth and nail and wipe the smile from his insolent face. Her fury was all the greater because, in her heart of hearts, she knew that he was right, that for all its wealth of gems this astonishing costume turned her warrior into a dandified figure of fun. If there had been a weapon to hand at that moment, she would have used it with no more hesitation than on that night at Selton. She had longed so desperately for Napoleon to appear before her enemy in all the stern and sombre majesty of his military uniform, to strike terror into his heart or at least to make him think twice before assailing her, Marianne, his accredited mistress. But instead of that, he had got himself up like an ageing Prince Florizel to marry this great, red-faced lump of a girl. Even so, she knew she must silence that hateful laughter which mocked at the only thing she had left in the world, her love.

Marianne drew herself up, her green eyes blazing in her bloodless face, and turned on Francis who was still laughing helplessly.

'Get out!' she told him fiercely. We have no more to say to one another. Get out of my carriage before I have you thrown out. Do you think I care what you may do? You can scatter your filthy broadsheets to the winds for all I care. Do as you please, but go! I never wish to see you again, and you will not get a penny from me!'

Her voice rose to a scream and in spite of the hubbub in the square heads were beginning to turn to look at them. Francis Cranmere had stopped laughing. His hand fastened on Marianne's arm, gripping it so that it hurt.

'Be quiet,' he commanded. 'Stop this nonsense! It can do no good. You will not escape me.'

'I am not afraid of you. As God is my witness, if you threaten me, I will kill you and this time no human aid will save you! You know me well enough to be sure that I mean what I say.'

'I told you to be quiet. I understand. You think yourself very strong, do you not? You think he loves you enough to defend you even against calumny, that he is powerful enough to protect you against any danger? Well, look at him! Bursting with joy and satisfied ambition! This, for him, is the crowning moment of his life. Think: he is marrying a Habsburg, he, a mere Corsican upstart! A niece to Marie-Antoinette! All this dazzling display of wealth and jewels, however preposterous, is laid on to impress her. Her wishes will be law to your Napoleon because he hopes that she will give him the heir who will establish his dynasty. And do you still believe that he will risk the displeasure of his precious Archduchess to protect a murderess? His spies in England will very soon tell him that you are indeed sought by the law for killing a defenceless woman and grievously wounding myself. What then? Believe me, Napoleon's watchword from now on will be: "No scandal, at any price!" '

Marianne felt an aching bitterness creep over her as he spoke. In an instant, all the confidence which she had based on the power of her love, on her influence with Napoleon, collapsed and fell in ruins. She knew that he cared for her, loved her perhaps as much as he was capable of loving any woman, but no more. The love the Emperor might feel for a woman of flesh and blood could not compete with the love he bore his Empire and his name. He had loved Josephine, had married her, crowned her, yet Josephine had been forced to step down from the throne and make way for this pink Austrian cow. He had loved the Polish countess, she had borne his child, and yet Marie Walewska had been packed off back to Poland in the depth of winter to bring the fruit of that love into the world. What were Marianne and all her charms beside the one to whom he looked for an heir to inherit his Empire and his name? Bitterly, Marianne recalled the careless tone in which he had said to her: 'I am marrying a womb!' That womb was more precious to him than the greatest love on earth.

Her eyes filled with tears and she saw through a glittering mist the bright forms of the newly-married pair, apparently borne up upon a sea of heads. Francis's voice came to her, persuasive and insinuating, as though out of a dream.

'Be sensible, Marianne, and be satisfied with your own power – a power it would be foolish to throw away for the sake of a few hundred ecus! What are fifty thousand livres to the queen of Paris? Boney will have given you as many again within the week.'

'I have not got them,' Marianne said shortly, angrily snuffing out an impending tear with the tip of her finger.

'But you will have in – shall we say – three days? I will let you know where and how to get them to me.'

'And what assurance have I that if I give them to you this will be the end of your infamous demands?'

Francis stretched his long arms with the lazy grace of a big cat and smiled a sleepy smile.

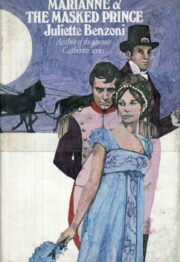

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.