Meanwhile, Clary's big travelling chaise was speeding through the wet and dripping woods on its way to Paris. The rain showed no signs of slackening. The low sky overhead was a depressing yellowish grey colour but neither of the vehicle's occupants appeared to notice it. Marianne, still very tired, sat huddled against the soft, red cushions, wrapped in the black, hooded cloak which Jolival had procured for her that morning, staring at the rain with unseeing eyes, her mind full of the scenes of the previous day. She recalled Napoleon's rapturous expression when he flung open the carriage door and beheld the Archduchess's plump cheeks framed by the absurd parrot feathers. She recalled the way he had held out his arms to hand her out into the courtyard at Compiègne.

Clary sat silently contemplating his companion's exquisite face, now white with exhaustion, the dark smudges round her green eyes, so touchingly shadowed by the soot-black lashes, and the perfection of the ungloved hand lying like a pale flower on her dark cloak. The diplomat could not help a feeling of surprise that this Italian nobody, an opera singer, should show such evident signs of breeding. The girl carried herself like a duchess, and her hands were those of a queen. And this air of secret sorrow, as if she bore some mysterious grief in her heart – it was this sense of mystery as much as Marianne's beauty which attracted Clary, and inspired him to behave towards her with the utmost respect. Throughout the long journey, he spoke only to assure himself that she was not cold or that she would not prefer to make a short stop, feeling almost absurdly pleased if she only smiled at him.

Wrapped in her own angry misery, Marianne was grateful to him for not intruding and she did not need any speeches to measure her effect on him: his eyes spoke eloquently enough.

It was long past nightfall when they entered Paris by way of Saint-Denis but Clary had not taken his eyes off Marianne, even when her face was no longer more than a vague blur in the dim interior of the chaise. He longed to know where his fair companion lived but, faithful to his self-imposed discretion, he said: 'Our way leads past the embassy. With your permission I will leave you there but my carriage will take you wherever you wish to go.'

His eyes said so clearly what he would not permit his lips to utter that Marianne could not resist a tiny smile.

'I thank you, Count, for your chivalry. I live at the Hôtel d'Asselnat in the rue de Lille… and I shall be happy to receive you if you should care to call.'

The chaise was drawing up outside the Austrian embassy at the junction of the rue du Mont-Blanc[1] and the rue de Provence. Blushing furiously, the diplomat bowed over the hand held out to him and brushed it with his lips.

'Be sure I shall give myself that pleasure tomorrow, madame. I trust I shall find you fully restored to health.'

Again, Marianne smiled. She had felt the young man's lips tremble against her hand and she was sure, now, of her power over him. She meant to make the fullest use of it. So it was with a great deal more cheerfulness that she re-entered her own house, to find Adelaide entertaining Fortunée Hamelin.

The two women were sitting in the music room talking earnestly when Marianne entered. Clearly, they had not expected her and both turned to stare at her in amazement. Madame Hamelin was the first to recover herself.

'Now, where have you sprung from?' she cried, hurrying to embrace her friend. 'Do you know everyone has been looking for you for a whole day?'

'Looking for me?' Marianne said, removing her cloak and hanging it on the big, gilt harp. 'Who has been looking for me, and why? Adelaide, you knew that I was obliged to go out of town.'

'Yes, indeed!' the old maid said indignantly. 'You were remarkably discreet about it, too, hinting that you were called away on the Emperor's business. So you may imagine my surprise when a messenger came here yesterday from the Emperor himself, inquiring after you.'

Feeling as if the ground had opened under her feet, Marianne sank down on the piano stool and stared at her cousin.

'A messenger from the Emperor? Inquiring after me? But why?'

'Why, to sing, of course! You are a singer are you not, Marianne d'Asselnat?' retorted Adelaide, with such a sting in her voice that Fortunée could not help smiling. It was clear that the thing which galled the aristocratic old lady most about Marianne's new life was the fact that she earned her living as a singer. To cut short these recriminations, the Creole stepped quickly over to Marianne and sat down, putting an arm about her friend's shoulders.

'I don't know what you have been up to,' she said, 'and I do not wish to pry into any secrets, but one thing is quite certain: yesterday an official request came from the Grand Marshal of the Palace for you to sing before the Court at Compiègne today.'

Marianne sprang to her feet with a sudden spurt of anger.

'Before the Court, was it? Or before the Empress? Because she is the Empress, you know, ever since last night, even before the wedding ceremonies have been completed!'

Fortunée blinked at this outburst. 'What are you saying?'

'That Napoleon took the Austrian to his bed last night! He slept with her! He couldn't wait for the wedding ceremony and the cardinal's blessing! He was so besotted about her, it seems, that he could not help himself! And now he dares – he dares to order me to go and sing before that woman! I, who only yesterday was his mistress!'

'And are still,' Fortunée observed placidly. 'My dear child, you must understand that to Napoleon there is nothing in the least shocking, or even unusual, in the idea of bringing his wife and his mistress face to face. Let me remind you that he has chosen more than one of his bedfellows from among Josephine's own ladies, and our Empress was obliged on numerous occasions to applaud the performance of Mademoiselle Georges – to whom, moreover, he even made a present of his wife's diamonds. Before your time no concert was complete without Grassini. Our Corsican Emperor has something of the Turk in him. Besides, I dare say he had a secret urge to see how you reacted to his Viennese. Well, he will have to be satisfied with la Grassini!'

'La Grassini?'

'Oh, yes, Duroc's messenger had orders, if the great Maria Stella were unavailable, to settle for the usual stand-by. You were absent, and so it is the opulent Giuseppina who was obliged to sing at Compiègne today. Mind you, I think it may have been just as well. There was to be a duet with Crescentini, the Emperor's favourite castrato, a dreadful, painted creature. You would have loathed him on sight, but Grassini adores him. In fact, she admires him as she does everything Napoleon chooses to honour, and he decorated Crescentini.'

'I wonder why?' Marianne said absently.

Fortunée gave a tinkling laugh which relaxed the atmosphere a little.

'That is the funny part! When Grassini was asked the same question, she said quite seriously: "Ah, but you forget his disability!"'

Adelaide generously echoed Fortunée's laughter but Marianne merely smiled perfunctorily. She was not sorry that she had not been at home. She found it hard to picture herself making her curtsey to the 'other woman' and indulging in a musical flirtation with a man who, apart from his exceptional voice, was no more than a hollow sham and could only make her ridiculous. Besides, she was too much a woman not to hope that, for a few seconds at least, it might occur to Napoleon to wonder where she was that she was unable to attend. Yes, all things considered, it was better so. The next time she beheld the man she loved, it would, she trusted, be in the company of someone who might well give him some anxious moments – supposing him capable of feeling jealousy on her account. The thought made Marianne smile in spite of herself and drew a waspish comment from Fortunée.

The delightful thing about you, Marianne, is that one can say anything to you and be quite sure you are not listening to a word of it. What are you thinking of now?'

'Not what, who. Of him, of course. Sit down, both of you, and I will tell you what I have been doing these last two days. But for heaven's sake, Adelaide, get me something to eat. I am starving.'

While she addressed herself with an energy remarkable in one who had been so ill only the night before to the sumptuous meal which Adelaide conjured up from the kitchen, Marianne described her adventures. But although the account contained a good deal of humour at her own expense, it did not make her two hearers laugh. Fortunée's expression, when she had finished, was extremely serious.

'But this assignation?' she said. 'It might have been important. Should you not have sent Jolival, at least?'

'I thought of it, but I did not want to part from him. I felt – so very desolate and unhappy. Besides, I am convinced it was a trap.'

'All the more reason to be sure. What if it were your – your husband?'

There was silence. Marianne set down the glass she had just drained with a bang that snapped the delicate stem. Her face was so white that Fortunée took pity on her.

'It was only an idea,' she said gently.

'But one that might have been checked. All the same, I don't see what motive he could have for getting me to that ruined castle, although I admit I did not think of him. I was thinking rather of the people who kidnapped me once before. What can I do now?'

'What you should have done straight away: inform Fouché and then wait. Whatever the attempt on you was to have been, whether it was a trap or a genuine rendezvous, there will certainly be another. By the way, let me congratulate you.'

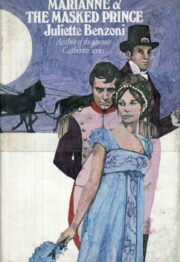

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.