“Oh, just point me in his general direction,” she said, and moved past him. “Is that lasagna I smell? I’m starving.”

“Do come in,” he said.

“Thanks,” she said over her shoulder. “Nice to meet you, Mr. Pettigrew.”

“It’s Major, actually …” he said, but she was already gone, stiletto heels clicking on the garish green and white tiles. She left a trail of citrus perfume in the air. It was not unpleasant, he thought, but it hardly offset the appalling manners.

The Major found himself loitering in the hall, unwilling to face what was inevitable upstairs. He would have to be formally introduced to the Amazon. He could not believe Roger had invited her. She would no doubt make his prior reticence out to be some sort of idiocy. Americans seemed to enjoy the sport of publicly humiliating one another. The occasional American sitcoms that came on TV were filled with childish fat men poking fun at others, all rolled eyeballs and metallic taped laughter.

He sighed. Of course, he would have to pretend to be pleased, for Roger’s sake. Best to brazen it out rather than to appear embarrassed in front of Marjorie.

Upstairs, the mood was slowly shifting into cheerfulness. With their grief sopped up by a heavy lunch and their spirits fueled by several drinks, the guests were blossoming out into normal conversations. The minister was just inside the doorway discussing the diesel consumption of his new Volvo with one of Bertie’s old work colleagues. A young woman, with a squirming toddler clasped to her lap, was extolling the benefits of some workout regime to a dazed Jemima.

“It’s like spinning, only the upper body is a full boxing workout.”

“Sounds hard,” said Jemima. She had taken off the festive hat and her highlighted hair was escaping from its bun. Her head slumped toward her right shoulder, as if her thin neck was having difficulty holding it up. Her young son, Gregory, finishing a leg of cold chicken, dropped the bone in her upturned palm and scampered off toward the desserts.

“You do need a good sense of balance,” the young woman agreed.

It was nice, he supposed, that Jemima’s friends had come to support her. They had created a little clump in the church, taking over several rows toward the front. However, he was at a loss to imagine why they had considered it appropriate to bring their children. One small baby had screamed at random moments during the service and now three children, covered in jam stains, were sitting under the buffet table licking the icing off cupcakes. When they were done with each cake, they slipped it, naked and dissolving with spit, back onto a platter. Gregory snatched an untouched cake and ran by the French doors where Marjorie stood with Roger and the American. Marjorie reached a practiced hand to stop him.

“You know there’s no running in the house, Gregory,” she said, grabbing his elbow.

“Ow!” he squealed, twisting in her grip to suggest she was torturing him. She gave a faint smile and pulled him close to bend down and kiss his sweaty hair. “Be good now, dearie,” she said and released him. The boy stuck out his tongue and scuttled away.

“Dad, over here,” called Roger, who had spotted him watching. The Major waved and began a reluctant voyage across the room between groups of people whose conversations had whipped them into tight circles, like leaves in a squall.

“He’s a very sensitive child,” Marjorie was telling the American. “High-strung, you know, but very intelligent. My daughter is having him tested for high IQ.” Marjorie did not seem at all offended by the interloper. In fact, she seemed to be doing her best to impress her. Marjorie always began impressing people by mentioning her gifted grandson. From there, she usually managed to work the conversation backward to herself.

“Dad, I want you meet Sandy Dunn,” said Roger. “Sandy’s in fashion PR and special events. Her company works with all the important designers, you know.”

“Hi,” said Sandy extending her hand. “I knew I was right about the butler thing.” The Major shook her hand, and raised his eyebrows at Roger, signaling him to continue with the introduction, even though it was all in the wrong order. Roger only gave him a big vacant smile.

“Ernest Pettigrew,” said the Major. “Major Ernest Pettigrew, Royal Sussex, retired.” He managed a small smile and added, for emphasis: “Rose Lodge, Blackberry Lane, Edgecombe St. Mary.”

“Oh, yes. Sorry, Dad,” said Roger.

“It’s nice to meet you properly, Ernest,” said Sandy. The Major winced at the casual use of his first name.

“Sandy’s father is big in the insurance industry in Ohio,” said Roger. “And her mother, Emmeline, is on the board of the Newport Art Museum.”

“How nice for Ms. Dunn,” said the Major.

“Roger, they don’t want to hear about me,” said Sandy. She tucked her hand through Roger’s arm. “I want to find out all about your family.”

“We have quite a nice art gallery in the Town Hall,” said Marjorie. “Mostly local artists, you know. But they have a lovely Bouguereau painting of young girls up on the Downs. You should bring your mother.”

“Do you live in London?” asked the Major. He waited, stiff with concern, for any hint that they were living together.

“I have a small loft in Southwark,” she said. “It’s near the new Tate.”

“Oh, it’s an enormous place,” said Roger. He was as excited as a small boy describing a new bike.

For a moment, the Major saw him at eight years old again, with a shock of brown curls his mother refused to cut. The bike had been red, with thick studded tires and a seat with springs like a car suspension. Roger had seen it at the big toy store in London, where a man did tricks on it, right on a stage inside the main door. The bike had completely pushed from his mind all memory of the Science Museum. Nancy, weary from dragging a small boy around London, had shaken her head in mock despair as Roger tried to impress upon them the enormous importance of the bike and the necessity for purchasing it at once. They had, of course, said no. There was plenty of room to adjust the seat on Roger’s existing bicycle, a solid-framed green bike that had been the Major’s at a similar age. His parents had stored it in the shed at Rose Lodge, wrapped securely in burlap and oiled once a year.

“The only problem is finding furniture on a big enough scale. She’s having a sectional custom made in Japan.” Roger was still boasting about the loft. Marjorie looked impressed.

“I find G-Plan makes a good couch,” she said. Bertie and Marjorie had acquired most of their furniture from G-Plan—good solid upholstered couches and sturdy square edged tables and chests of drawers. The choice might be limited, Bertie used to say, but they were solid enough to last a lifetime. No need to ever change a thing.

“I hope you ordered it with slipcovers,” Marjorie advised. “It lasts so much better than upholstery, especially if you use antimacassars.”

“Goatskin,” said Roger. There was great pride in his voice. “She saw my goatskin lounger and said I was ahead of the trend.”

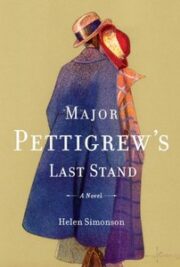

"Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand" друзьям в соцсетях.