“Will you not come into the house? I hear you have brought a guest. The women should have attended to you better.”

“But it was my wish to speak to you alone … out here while you worked among your flowers.”

She was startled. She knew that he had something important to say, and she wondered whether he preferred to say it out of doors because even in well-ordered houses such as hers servants had a habit of listening to what they should not.

A cold fear numbed her mind as she wondered if he had come to tell her that this was the end of their liaison. She was acutely conscious of her thirty-eight years. She guarded her beauty well, but even so, a woman of thirty-eight who had borne several children could not compete with young girls; and there could scarcely be a young girl who, if she could resist the charm of the Cardinal, would be able to turn away from all that such an influential man could bring a mistress.

“My lord,” she said faintly, “you have news.”

The Cardinal lifted his serene face to the sky and smiled his most beautiful smile.

“My dear Vannozza,” he said, “as you know, I hold you in the deepest regard.” Vannozza caught her breath in horror. It sounded like the beginning of dismissal. “You live here in this house with our three children. It is a happy little home, but there is something missing; these children have no father.”

Vannozza wanted to cast herself at his feet, to implore him not to remove his benevolent presence from their lives. They might as well be dead if he did. As well try to live without the sun. But she knew how he disliked unpleasant scenes; and she said calmly: “My children have the best father in the world. I would rather they had never been born than that they should have had another.”

“You say delightful things … delightfully,” said Roderigo. “These are my children and dearly I love them. Never shall I forget the great service you have done me in giving them to me, my dearest love.”

“My lord.…” The tears had come to her eyes and she dashed them away, but Roderigo was looking at the sky, so determined was he not to see them.

“But it is not good that you should live in this house—a beautiful and still young woman, with your children about you, and only the uncle of those children to visit you.”

“My lord, if I have offended you in some way I pray you tell me quickly where I have been at fault.”

“You have committed no fault, my dear Vannozza. It is but to make life easier for you that I have made these plans. I want none to point at you and whisper: ‘Ah, there goes Vannozza Catanei, the woman who has children and no husband.’ That is why I have found a husband for you.”

“A husband! But, my lord …”

Roderigo silenced her with an authoritative smile. “You have a young baby in this house, Vannozza; she is six months old. Therefore you must have a husband.”

This was the end. She knew it. He would not have provided her with a husband if he had not tired of her.

He read her thoughts. But it was not entirely true that he was weary of her; he would always have some affection for her and would continue to visit her house, but that would be mainly to see his children; there were younger women with whom he wished to spend his leisure. There was some truth in what he was telling her; he did think it wise that she should be known as a married woman, for he could not have it said that his little ones were the children of a courtesan.

He said quickly: “Your husband’s duties will be to live in this house, to appear with you in public. They will end there, Vannozza.”

“Your lordship means?”

“Do you think that I could mean anything else? I am a jealous lover, Vannozza. Have you not yet learned that?”

“I know you to be jealous when you are a lover, my lord.”

He laid his hand on her shoulder. “Have no fear, Vannozza. You and I have been together too long to part now. It is solely for the sake of our children that I take this step. And I have chosen a quiet man to be your husband. He is a good man, a man of great respectability, and he is prepared to be the only sort of husband I could content myself with giving you.”

She took his hand and kissed it.

“And your Eminence will come and visit us now and then?”

“As ever, my dear. As ever. Now come and meet Giorgio di Croce. You will see that he is a mild-tempered man; you will have no difficulty with such a one, I do assure you.”

She followed him into the house, wondering what inducement had been offered to this man that he had agreed to marry her. It was not difficult to guess. There would be scarcely a man in Rome who would refuse to marry a woman whom the influential Cardinal had selected for him.

Vannozza was uneasy. She did not care to be bartered thus, as though she were a slave. She would certainly keep Giorgio di Croce in his place.

In her room which overlooked the piazza he was waiting. He rose as they entered and the Cardinal made the introductions.

The mild-tempered man took her hands and kissed them; she studied him and saw that his pale eyes gleamed as he took in her voluptuous charm.

Did the Cardinal notice? If so, he gave no sign.

From the loggia of her mother’s house Lucrezia looked out on the piazza and watched with quiet pleasure the people who passed. The city of the seven hills outside her mother’s house fascinated her, and it was her favorite pleasure to slip out to the loggia and watch people passing over the St. Angelo Bridge. There were Cardinals on white mules whose silver bridles gleamed in the sunshine; there were masked ladies and gentlemen; there were litters, curtained so that it was impossible to see the occupants.

Lucrezia’s wide wondering eyes would peer through gaps in the masonry as her fat little fingers curled about the pillars.

She was two years old but life with her brothers had made her appear to be more. The women of the nursery loved her dearly for, although she was like her brothers in appearance, she was quite unlike them in character. Lucrezia’s was a sunny nature; when she was scolded for a fault, she would listen gravely and bear no malice against the scolder. It was small wonder that in that nursery, made turbulent by the two boys, Lucrezia was regarded as a blessing.

She was very pretty, and the women never tired of combing or adorning that long hair of the yellow-gold color which was so rarely seen in Rome. Lucrezia was already, at two—like her brothers she was precocious—aware of her charm, but she accepted this in quiet contentment as she accepted most things.

Today there was a hush over the house, because something important was happening, and Lucrezia was aware of the whispers of serving men and maids, and of the presence of strange women in the house. It concerned her mother, she knew, because she had not been allowed to see her for a whole day. Lucrezia smiled placidly as she looked on the piazza. She would know in time, so she would wait until then.

Her brother Giovanni came and stood beside her. He was six years old, a beautiful boy with auburn hair like his mother’s.

Lucrezia smiled at him and held out her hand; her brothers were always affectionate toward her and she was already aware that each of them was doing his best to be her favorite. She was coquette enough already to enjoy the rivalry for her affections.

“For what do you watch, Lucrezia?” asked Giovanni.

“For the people,” she answered. “See the fat lady with the mask!”

They laughed together because the fat lady waddled, said Giovanni, like a duck.

“Our uncle will soon be here,” said Giovanni. “You are watching for him, Lucrezia.”

Lucrezia nodded, smiling. It was true that she always watched for Uncle Roderigo. His visits were the highlights of her life. To be swung in those strong arms, to be held above that laughing face, to smell the faint perfume which clung to his clothes and watch the twinkling jewels on his white hands and to know that he loved her—that was wonderful. Even more wonderful than being loved so much by her two brothers.

“He will come today, Lucrezia,” said Giovanni. “He surely will. He is waiting for a message from our mother.”

Lucrezia listened, alert; she could not always understand her brothers; they seemed to forget that she was only two years old, and that Giovanni who was six and Cesare who was seven seemed like adults, grand, large and important.

“Do you know why, Lucrezia?” said Giovanni.

When she shook her head, Giovanni laughed, hugging the secret, longing to tell yet reluctant to do so because the anticipation of telling so pleased him. He stopped smiling at her suddenly and Lucrezia knew why. Cesare was standing behind them.

Lucrezia turned to smile at him, but Cesare was glaring at Giovanni.

“It is not for you to tell,” said Cesare.

“It is as much for me as for you,” retorted Giovanni.

“I am the elder. I shall tell,” declared Cesare. “Lucrezia, you are not to listen to him.”

Lucrezia shook her head and smiled. No, she would not listen to Giovanni.

“I shall tell if I want to,” shouted Giovanni. “I have as much right to tell as you. More … because I thought to tell first.”

Cesare had his brother by the hair and was shaking him. Giovanni kicked out at Cesare. Cesare kicked back, Giovanni yelled and the two boys were rolling on the floor.

Lucrezia remained placid, for such fights were commonplace enough in the nursery, and she watched them, content that they should be fighting over her; she was nearly always the cause of these fights.

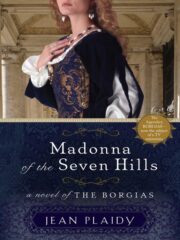

"Madonna of the Seven Hills" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills" друзьям в соцсетях.