He had turned from the shrine before which he had been kneeling. The lamp which burned constantly before the figures and pictures of the saints had shone on the serene face of the Madonna, and he had fancied he had seen reproach there. Should he, one of the mightiest of Cardinals, be praying for the safe delivery of a child he had no right to have begotten? Could he expect the Madonna to grant him a son—a beautiful healthy boy—when, as a son of the Church himself, he was sworn to celibacy?

It was an uncomfortable thought and as Roderigo always turned hastily from such, he allowed himself to forget the shrine and looked instead at the emblem of the grazing bull which adorned the walls, and which never failed to inspire him. It was the emblem of the Borgias and one day it would be, so determined Roderigo, the most feared and respected symbol in Italy.

Ah yes, it was comforting to contemplate the bull—that creature of strength, peacefully grazing yet indicative of so much that was fierce and strong. One day, pondered the Cardinal, the Borgia arms should be displayed all over Italy, for it was the dream of Roderigo that the whole of Italy would one day be united, and united under a Borgia. Another Borgia Pope! Why not? The Vatican was the center of the Catholic world; certainly the Vatican should unite a divided country, for in unity there was strength, and who more fitted to rule a united Italy than the Pope? But he was not yet Pope, and he had his enemies who would do all in their power to prevent his reaching that high eminence. No matter. He would achieve his ambition as his uncle Alfonso had achieved his when he had become Pope Calixtus III.

Calixtus had been wise; he had known that the strength of a family was in its young members. That was why Calixtus had adopted him, Roderigo, and his brother Pedro Luis (after him he had named Vannozza’s eldest boy), that was why he had enriched them and made them powerful men in the land.

Roderigo smiled complacently; he had no need to adopt children; he had his own sons and daughters. The daughters were useful when it came to making marriages which would unite eminent families with the Borgias; but sons were what an ambitious man needed and, praise be to the saints, these were what he had, and he would forever be grateful to the woman, who was now in childbed in this very castle, for providing them. Pedro Luis in Spain would ensure that country’s benevolence toward his father; dashing young Giovanni—for him Roderigo had the most ambitious plans, for that best loved of his sons should command the armies of the Borgias; and Cesare, that bold young scamp (Roderigo smiled with pleasure at the memory of his arrogant little son), he must perforce go into the Church, for, if the Borgias were to achieve all that Roderigo planned for them, one of them must hold sway in the Vatican. So little Cesare was destined to follow his father to the Papal Chair.

Roderigo shrugged his shoulders, and smiled gently at himself. He had yet to achieve that position; but he would; he was determined that he would. The gentle smile had faded and for a few moments it was possible to see the man of iron behind the pleasant exterior.

He had come far and he would never go back; he would prefer death rather. He was as certain as he was that a child was being born in his castle of Subiaco that one day he would ascend the Papal throne.

Nothing … nothing should stand in his way, for only as Pope could he invest his sons with those honors which would enable them to work toward that great destiny which was to be the Borgias’.

And the new child? “A boy,” he prayed, “Holy Mother, let it be a boy. I have three fine sons, healthy boys, yet could I use another.”

He was all gentleness again, thinking of the nursery in the house on the Piazza Pizzo di Merlo. How those two little ones delighted in the visits of Uncle Roderigo! It was necessary at present that they should think of him as “uncle”; it would be quite inconceivable that he—a Holy Cardinal—should be addressed as Papa. “Uncle” was good enough for the present; one day those little boys should know who they really were. He looked forward to his pleasure in telling them. (Roderigo enjoyed bringing pleasure to those whom he loved but if there was any unpleasant task to perform he preferred others to do it.) What glorious fate awaited them because he, the illustrious Cardinal, was not merely their uncle, but their father! How Cesare’s eyes would flash—the arrogant and delightful little creature! How Giovanni would strut—dear, best-beloved Giovanni! And the new child … he too would come in for his share of honors.

What were they doing now? Disagreeing with their nurse-maid, very likely. He could imagine the threats of Cesare, the sullen anger of Giovanni. They were brimming with vitality—inherited from Vannozza as well as from their father, and each knew how to achieve his desires. They would get the better of twenty nursemaids—which was what he must expect. They were the sons of Roderigo Borgia, and when had he failed to get his way with women?

Now he was thinking of the past, of the hundreds of women who had pleased him. When he had first gone into the Church he had been dismayed because celibacy was expected of him. He could laugh at his naïvety now. It had not taken him long to discover that Cardinals, and even Popes, had their mistresses. They were not expected to lead celibate lives, only to appear to do so, which was quite a different matter. Not continence but discretion was all that was asked.

It was a solemn moment when a new life was about to begin; it was even more solemn to contemplate that, but for an act of his, this child would not have been preparing to come into the world.

He sat down and, keeping his eyes on the grazing bull, recalled those incidents in his life which had been of greatest importance to him. Perhaps one of the earliest and therefore the most important, for if it had not happened, all that had followed would not have been possible, was when his uncle Calixtus III had adopted him and his brother Pedro Luis and promised that he would treat them as his own sons if they would discard their father’s name of Lanzol and called themselves Borgia.

Their parents had been anxious that the adoption should take place. They had daughters—but Pope Calixtus was not interested in them, and they knew that no better fate could befall their sons than to come under the immediate patronage of the Pope. Their mother—the Pope’s own sister—was a Borgia, so it merely meant that the boys should take their mother’s name instead of their father’s.

That was the beginning of good fortune.

Uncle Alfonso Borgia (Pope Calixtus III to the world) was Spanish and had been born near Valencia. He had come to Italy with King Alfonso of Aragon when that monarch had ascended the throne of Naples. Spain—that most ambitious Power which was fast dominating the world—was eager to see Spanish influence throughout Italy, and how could this be better achieved than by the election of a Spanish Pope?

Uncle Alfonso had the support of Spain when he aspired to the Papacy, and he was victorious in the year 1455. All Borgias were conscious of family feeling. They were Spanish, and Spaniards were not welcome in Italy; therefore it was necessary for all Spaniards to stand together while they did their best to acquire the most important posts.

Calixtus had plans for his two nephews. He promptly made Pedro Luis Generalissimo of the Church and Prefect of the City. Not content with this he created him Duke of Spoleto and, in order that his income should be further increased, he made him vicar of Terracina and Benevento. Pedro Luis was very comfortably established in life; he was not only one of the most influential men in Rome—which he would necessarily be, owing to his relationship with the Pope—he was one of the most wealthy.

The honors which fell to Roderigo were almost as great. He, a year younger than Pedro Luis, was made a Cardinal, although he was only twenty-six; later there was added to this the office of Vice-Chancellor of the Church of Rome. Indeed, the Lanzols had no need to regret the adoption of their sons by the Pope.

It had been clear from the beginning that Calixtus meant Roderigo to follow him to the Papacy; and Roderigo had made up his mind, from the moment of his adoption, that one day he would do so.

Alas, that was long ago, and the Papacy was as far away as ever. Calixtus had been an old man when he was elected, and three years later he had died. Now the wisdom of his prompt action in bestowing great offices on his nephews was seen, for even while Calixtus was on his death-bed, there was an outcry against the Spaniards who had been given the best posts; and the Colonnas and the Orsinis, those powerful families which had felt themselves to be slighted, rose in fury against the foreigners; Pedro Luis had to abandon his fine estates with all his wealth and fly for his life. He died shortly afterward.

Roderigo remained calm and dignified, and did not leave Rome. Instead, while the City was seething against him and his kin, he went solemnly to St. Peter’s in order that he might pray for his dying uncle.

Roderigo was possessed of great charm. It was not that he was very handsome; his features were too heavy for good looks, but his dignity and his presence were impressive; so was his courtly grace which rarely failed to arouse the devotion of almost all who came into contact with him.

Oddly enough those people who were raging against him parted to let him pass on his way to St. Peter’s while benignly he smiled at them and gently murmured: “Bless you, my children.” And they knelt and kissed his hand or the hem of his robes.

Was that one of the most triumphant hours of his life? There had been triumphs since; but perhaps on that occasion he first became aware of this great power within him to charm and subdue by his charm all who would oppose him.

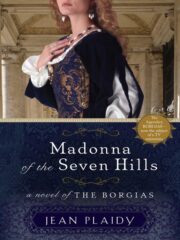

"Madonna of the Seven Hills" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Madonna of the Seven Hills" друзьям в соцсетях.