So there was the autumn and winter—roaring fires and chestnuts popping on the hearth; the muffin man; hansom cabs clopping by. Peering out to watch them and wondering about the people who were riding in them, I would invent all sorts of stories to which Esmeralda would listen enthralled and then she would say: "How can you know who are in them and where they are going?" I would narrow my eyes and whistle. "There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Esmeralda Loring, than you wot of in your philosophy." She would shiver and regard me with awe (which I very much enjoyed). I would quote to her often, and sometimes pretend I had made up the words I spoke. She believed me. She could not learn as quickly as I could. It was a pity that she was so ineffectual. It gave me an exaggerated idea of my own cleverness. However, Cousin Agatha did her best to rid me of that; and perhaps, as I gathered from the servants' gossip and Cousin Agatha's manner towards me that I was of not much account, it was not so unfortunate after all, for I needed something to keep up my confidence.

I was adventurous and this gave rise to the speculation that I had a streak of wickedness in me. I loved the markets particularly. There were none in our district, but some of the servants used to go to them and I would hear them talking. Once I prevailed on Rosie, one of the parlormaids, to take me with her. She was a flighty girl who had always had a lover and had at last found one who wanted to marry her. There was a great deal of talk about her "bottom drawer," and she was always collecting "bits and pieces" for it. She would bring them into the kitchen. "Look what I've found in the market," she would cry, her eyes sparkling. "Dirt cheap it was."

As I said, I persuaded her to take me to the market. She liked to act outside the law too. She was rather fond of me and used to talk to me about her lover. He was the Carringtons' coachman and she was going to live in a mews cottage with him.

I shall never forget that market with its naphtha flares and the raucous Cockney voices of men and women calling their goods. There were stalls on which mounds of apples, polished until they shone, were arranged side by side with oranges, pears and nuts. It was November when I first saw it, and already holly and mistletoe were being displayed among the goods. I admired the crockery, the ironmongery, the secondhand clothes, the stewed and jellied eels to be eaten on the spot or taken home, and I sniffed ecstatically at the cloud of appetizing steam which came from the fish-and-chip shop. Most of all I liked the people, who bargained at the stalls and jostled and laughed their way through the market. I thought it was one of the most exciting places I had ever visited. I returned with Rosie starry-eyed and wove stories around the market to impress Esmeralda.

I rashly promised that I would take her there. After that she kept asking about the market and I made up outrageous stories about it. These usually began: "When Rose and I went to the market ..." We had the most fantastic adventures there—all in my mind—but they had Esmeralda breathless with excitement.

Then the day came when we actually went there and what followed brought me to the notice of the great Rollo himself. It was about a week before Christmas, I remember—a darkish day with the mist enveloping the trees of the Park. I loved such days. I thought the Park looked like an enchanted forest bathed in that soft bluish light, and as I looked out on it I thought to myself: "I'll take Esmeralda to the market."

Of course this was the day. There was to be a dinner party that night. The household could think of nothing else. "She's got the wind in her tail, that's what," said the cook, referring to Cousin Agatha. I knew what she meant. Cousin Agatha's voice could be heard all over the house. "Miss Hamer" (that was her long-suffering social secretary), "have you the place names ready? Do make sure that Lady Emily is on the master's right hand; and Mr. Carrington on mine. Mr. Rollo should be in the center of the table on the master's right-hand side of course. And have the flowers come?" She swept through the house like a hurricane. "Wilton" (that was the butler), "make sure the red carpet is down and the awning in place and see to it in good time." Then to the lady's maid Yvonne, "Do not let me sleep after five o'clock. Then you may prepare my bath."

She was in the kitchen admonishing the cook ("As if I don't know my business," said Cook). She sent for Wilton three times in the morning to give him instructions to be passed on to the other servants.

It was that sort of day. I met her on the stairs and she walked past me without even seeing me. And I thought again: "This is surely the time to go to the market." Nanny Grange was pressed into service with the goffering iron; our governess was to help arrange the flowers. So there we were "sans governess, sans nanny, sans supervision, sans everything," as I misquoted to Esmeralda.

"It's the very day when we could get away and be back before they noticed." The market should be seen by the light of flares and it grows dark soon after half past four in December. "The flares are like erupting volcanoes," I exaggerated to Esmeralda, "and they don't light them until dark."

I told Nanny Grange that Esmeralda and I would look after ourselves, and soon after afternoon tea, taken at half past three that day to get it over quickly, we set out. I had carefully noted the number of the omnibus and the stop where we had got off and we reached the market without mishap. It was then about five o'clock.

I gleefully watched the wonder dawn in Esmeralda's eyes. She loved it: the shops with their imitation snow on the windows—cotton wool on string but most effective—the toys in the windows. I dragged her away from them to look in the butcher's with the pigs' carcasses hanging up, oranges in their mouths, and the great sides of beef and lamb and the butcher in blue-striped apron sharpening long knives and crying "Buy, buy, buy."

Then there were the stalls piled with fruit and nuts and the old-clothes man and the people eating jellied eels out of blue-and-white basins. From one shop came the appetizing odor of pea soup, and we looked inside and saw people sitting on benches drinking the hot steaming stuff; there was the organ grinder with his little monkey sitting on top of the organ and the cap on the ground into which people dropped money.

I was delighted to see that Esmeralda was of the opinion that I had not for once exaggerated the charms of the market.

When the organ grinder's wife began to sing in a rather shrill penetrating voice the people started to crowd round us and as we stood there listening a cart on which there was a considerable amount of rattling ironmongery came pushing its way through the crowds.

"Mind your backs," cried a cheerful voice. "Make way for Rag and Bone 'Arry. Stand aside please... ."

I leaped out of the way and was caught up in the press of people who carried me with them to the pavement. Several of them called out to Rag and Bone 'Arry as he passed, to which he answered in a good-natured and pert manner. I watched with interest and found myself wondering about Rag and Bone 'Arry and all the people around me when suddenly I realized that Esmeralda was not beside me.

I looked about me sharply. I fought my way through the crowd; I called her name, but there was no sign of her.

I didn't panic immediately. She must be somewhere in the market, I told myself, and she couldn't be far away. I had presumed that she would keep close to me; I had told her to and she was not of an adventurous nature. I scanned the crowds, but she was nowhere to be seen. After ten minutes of frantic searching I began to be really afraid. I had charge of the money, taken with a great deal of trouble from our money boxes, into which it was so easy to put coins and so hard to take them out (the operation must be performed by inserting the blade of a knife through the slit, letting the coin drop onto the knife and then drawing it out). Without money how could she get home by herself? After half an hour I began to be very frightened. I had brought Esmeralda to the market and lost her.

My imagination—so exciting at times when I was in control of it—now showed itself as a ruthless enemy. I saw Esmeralda snatched up by some evil characters like Fagin from Oliver Twist teaching her to pick pockets. Of course she would never learn, I promised myself, and would be arrested immediately and brought home to her family. Perhaps Gypsies would take her. There was a fortuneteller in the market. They would darken her skin with walnut juice and make her sell baskets. Someone might kidnap her and hold her to ransom; and I had done this. The market adventure was so daring that it could only have been undertaken when it was possible to sneak into the house as we had sneaked out. Only on such a day when there was to be an important dinner party had it been possible.

And now Esmeralda was lost. What could I do? I knew. I must go back to the house. Confess what I had done and search parties would be sent out to find her.

This was distasteful to me, for I knew it was something which would never be forgotten and might even result in my being sent into an orphanage. After I had committed such a sin Cousin Agatha would in her opinion be justified in sending me away. I suspected that she only needed such justification. I therefore found it difficult to leave the market. Just one more look, I promised myself, and I wended my way through the place keeping my eyes alert for Esmeralda.

Once I thought I caught a glimpse of her and gave chase, but it was a mistake.

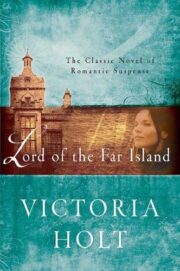

"Lord of the Far Island" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lord of the Far Island". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lord of the Far Island" друзьям в соцсетях.